Are we too fixated on rural electrification?

How should energy and electrification demands be prioritised by policymakers? Today's blog asks if rural electrification is over-prioritised in development and donor circles. Would industrial, educational, and health sector electrification be better than rural electrification for improving people's lives?

“Rural electrification” and “energy access” are catchphrases in many energy and development circles. Multilateral lending agencies, many NGOs and the UN are highlighting the 1.3 billion people who currently do not have electricity in their homes. For example, of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, number 7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.” Similarly, the UN and the World Bank launched the Sustainable Energy For All initiative in 2011, whose name basically defines their vision.

Electricity is certainly a vital part of modern life. Without it, people can’t watch TV, refrigerate food and medicine, charge a cell phone, protect themselves from extreme heat, or do many of the things those of us in the developed world take for granted.

I’m concerned, however, that development efforts may be misdirected because of the near singular focus in the energy sphere on this particular goal. I’m worried about two potential outcomes – that we’ll stop short or that we’ll go too far. My concerns may seem contradictory, but I fear that both are made more likely by focusing too exclusively on one binary measurement. (I’ll leave for another blog post the messy ethics of focusing on sustainable energy access – achieving energy access with green sources.)

Perils of Stopping Short

Here’s the potential problem with stopping short. I worry that once a household has a small solar home system, the data collectors will declare it “electrified” and policy makers will put a checkmark in the electricity box and declare victory. But, solar home systems provide very limited services at high per kWh prices and don’t allow people to do many of the things we associate with modern energy access.

For example, mKopa, the leading solar provider in Kenya, sells a tiny 8 Watt system that comes with 3 LED bulbs, a radio and a cell phone charging station. (Unfortunately, this very system was championed in a New York Times op-ed recently.)

The world’s chief energy data collectors at the International Energy Agency recognize that “[a]ccess to electricity involves more than a first supply to the household,” and claim that an appropriate definition of electricity access would include a minimum annual kWh usage level. But, they conclude that:

[t]his definition cannot be applied to the measurement of actual data simply because the level of data required does not exist in a large number of cases. As a result, our energy access databases focus on a simpler binary measure of those that do not have access to electricity…

I am part of a working group at the Center for Global Development that’s advocating for better data and reporting on energy access. A report is due out soon.

Perils of Going Too Far

The dangers associated with going too far are subtler, and may not be empirically relevant, but let me describe my concerns. As the chart below demonstrates, there is clearly a strong positive relationship across countries between GDP per capita and electricity consumption per capita. (The figure plots the natural log of both variables, so you can think of the relationship reflecting percent changes.) The same pattern holds for lots of other development indicators besides GDP per capita.

Let’s assume that we know the relationship in the above figure is causal, meaning that driving up electricity consumption in a country will cause its per capita GDP to grow. What the chart misses is that not all kWh are created equally. A kWh that replaces a kerosene lamp with a CFL for a month may not be the same as a kWh that helps power a factory that employs 10 people for an hour, and one may have a larger impact on development than the other.

What if governments are less likely to electrify schools if they’re focusing on homes? Or, what if utilities that spend more money on building out their electricity systems to reach homes can spend less money on ensuring factories or hospitals get reliable electricity?

None of the Sustainable Development Goals are targeting the number of schools with electricity or the number of industries with reliable electricity supply, and, to my knowledge, we don’t have a firm analytical grasp on whether spending money on rural versus industrial or health sector electrification helps improves people’s lives by more.

I am not denying that rural electrification brings benefits. Nonetheless, any expenditure of public, World Bank or NGO money has an opportunity cost, so spending money on rural electrification means we can’t spend money somewhere else.

This struck me seeing the juxtaposition of a sleek new electricity meter on a Kenyan woman’s mud wall. She liked replacing her kerosene lamp with an electric light bulb and her neighbor liked having TV, but connecting her to the grid is not cheap. What else could the government have done with that money that may have helped this woman more than the electricity connection?

We asked another woman in the compound whether she would prefer her electricity connection or a new motorbike. She said electricity. But when we gave her the choice between better health services or electricity and better education for her kids or electricity, she chose both of those over electricity. If this woman is representative, electrification in rural households is not yet the right priority.

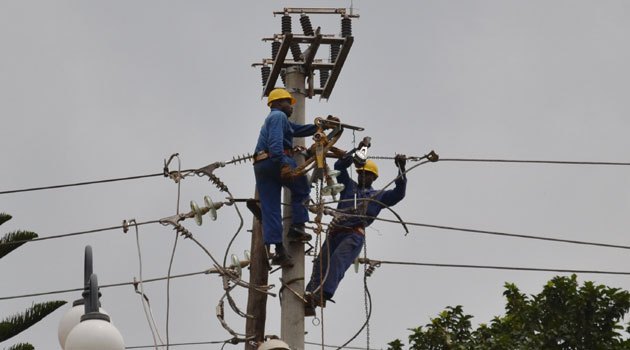

That said, there are reasons to believe I don’t need to worry about going too far. It is entirely possible that building out the electricity grid to reach homes will make countries more likely to connect health centers and schools, and not less likely. Also, there could be a lot of benefits that come from rural electrification that wouldn’t be captured if the kWh were directed at factories – what economists call spillovers. For example, one person interviewed in an NPR story (which features my co-author Ted Miguel) described how getting an electricity connection made him feel, “part of Kenya.” Similarly, introducing this young boy to engineers installing electricity at his home may incite an interest in engineering and make him more likely to go to university. These indirect effects are difficult to measure, but they may be very important.

Governments and NGOs need to figure out how to get the biggest bang for their buck. So, we need more data and more analysis to figure out the best way to improve people’s lives and how big a role there is for rural electrification. It may turn out that rural electrification has high payoffs relative to alternatives, but there are risks to forging ahead without a richer understanding of how electricity drives economic growth, improved quality of life, and other development goals.

This blog originally appeared on the Energy Institute at Haas.