Assessing the impact of demonetisation through the gender lens

As the chaos following the Government of India’s surprising decision to take Rs.500 and Rs.1000 notes out of circulation unfolds, Mitali Nikore highlights how the move is impacting women, and offers policy suggestions on how the negative effects can be mitigated.

Currency demonetisation is no doubt one of the boldest, yet most operationally onerous actions in the fight against black money undertaken in the recent history of India. As millions processed the shock of their cash holdings becoming devoid of any value on the morning of 9 November 2016, my thoughts went to the differential impact of this move on men and women. This article aims to point out some of the specific issues women may face as a consequence of this action, particularly due to lack of agency and access to formal banking, as well as certain specific recommendations for the government to ensure a successful transition, and move towards a cashless economy.

Differential impact of currency demonetisation on women

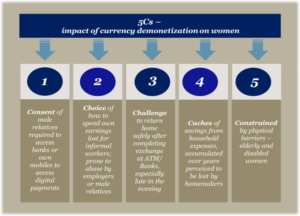

On the day after the announcement, several opinion polls, published in the news and social showed that more than 90% of people surveyed supported the government’s action of currency demonetisation, popularly terming it a ‘surgical strike’ on the black economy, and applauding the secrecy and element of surprise associated with the announcement. However, stories of distress started in the days that followed, when people complained of long queues, dysfunctional ATMs and differential access to the new currency. Stories of women in distress began circulating, with the All-India Democractic Women’s Association and the All-India Progressive Women’s Association decrying the PM’s actions as disastrous for women. Stepping away from the pandemonium – does currency demonetisation impact women differently? And if so, how? My answer: a definite and resounding yes, as shown through the five channels of impact below.

1. Consent: As per a UNDP study, 80% of women in India don’t have bank accounts, as of FY15. Women (across socio-economic groups) are often accompanied by male relatives who deal with banking officials to open a new bank account, make deposits, etc. on behalf of their female relatives. Documents carrying the name/signatures of a father or a husband are often a requirement. Opening and operating accounts on mobile wallets requires mobile phones (preferably smartphones equipped with access to the internet) to begin with, which several women may not even own. Therefore, in essence, women require the consent of male relatives to access formal financial channels, whereas cash offers them a certain amount of independence.

2. Choice: Informal workers including domestic help, agricultural laborers, workers in factories, micro-business owners, daily-wage workers, etc. receiving their salary in cash are severely disadvantaged. They often lack formal documentation required for exchanging their currency notes, and also suffer from time poverty, as they may not be allowed to take leave to get their currency exchanged. This disadvantage is amplified for female informal workers, particularly sex workers, as they become vulnerable to abuse from employers. Given that these women bear the triple burden of household work, childcare as well as wage labour, they would find it difficult to stand in daily queues for currency exchanges. Consequently, they are likely to lose agency over their earnings if the exchange is handled by male relatives/employers. Overall, their choice over their time and earnings, when compared with men, as a result of demonetisation.

Image: A predominantly male crowd queues for an ATM in Brahmapuri. Credit: Ganesh Dhamodkar CC BY 2.0

Image: A predominantly male crowd queues for an ATM in Brahmapuri. Credit: Ganesh Dhamodkar CC BY 2.0

3. Challenge due to safety concerns: A casual observation of scenes outside ATMs make it apparent that there are far fewer women in queues. A woman was recently met by astounded stares at an ATM in Delhi at just 9pm in the evening, as she has committed the gross mistake of arriving there alone, without a male relative to chaperone. Women frequently do not risk going out alone late in the evening owing to the ever imminent threat of violence, be it cities or rural areas. This effectively reduces the time women have to access ATMs, thus making cash exchange far more challenging for women than men.

4. Cache of savings: Stories abound of huge caches of savings stashed in the form of cash by homemakers, away from the prying eyes of husbands and other family members. The perception that years of savings that housewives often put away from household expense budgets would be rendered value-less compounded with the need to be disclose their quantum to the husband/family, severely impacts homemakers, even though they may be facing less scrutiny from the tax department. Further, for women who may be victims of physical, mental or emotional domestic abuse, cash is a safety net, having higher utility than even its monetary In these cases, women may be hesitant to disclose their savings, fearing abuse from husband/family members, and would end up facing greater insecurity in the future.

5. Constrained by physical barriers: Despite recent measures (such as dedicating a full day for currency exchange of senior citizens) the physical barriers preventing access to banks, further intensified by the misinformation that there lifelong savings may be lost, can have a debilitating psychological impact on elderly and disabled. Mobile wallets and net banking can be difficult to understand owing to technological barriers. This impact is compounded in women’s case, as they are generally used to their husbands/male relatives handling “money related matters”.

How can this be remedied? Immediate and longer term measures

While it is understood that demonetisation has been undertaken with a larger objective of eradicating the black money circulating in the form of cash, the differential impact on women necessitates that central and state governments, in partnership with NGOs, banks and mobile wallet operators, ensure a smooth exchange of currency for women in this period, as well as work towards improving women’s access to non-cash based payment methods in the longer run. Some of the possible steps which could be taken in both the short and longer term could be as follows:

1. Camps for encouraging women to open banks accounts: Urban local bodies/ village panchayats bodies could tie-up with banks to set up Aadhaar card registration and Jan Dhan Yojana camps, wherein persons lacking formal documents can register for an Aadhar card and set up a bank account under the Jan Dhan Yojana, This round of registrations could include specific targets to enlist women. Special female volunteers could be recruited at community-level to educate women about the need to have independent bank accounts, and be taught how to operate them without male family members. This can be a short-term measure, which could be implemented until 30 December 2016, at the district level.

2. Currency exchange services for women: Akin to the recent dedicated day for senior citizens, women could also be provided certain special currency exchange services. Banks and post offices could set-up separate queues for women; Resident Welfare Associations (RWA), community groups and village panchayats could partner with banks to set up women-only, physically accessible currency-exchange centres, with physically accessible facilities.

These could be set-up on a single day of the week or on weekends, and women could be allowed to exchange an amount equivalent to the weekly withdrawal limit in one go at these centres. Volunteers could be selected by the RWA/village panchayat to help elderly and disabled (men and women) with the cash exchange at these centres – community level checks could be in place to ensure that only the cash of the elderly is exchanged, rather than that of family members. Women lacking formal documentation could be allowed to exchange their cash at these centres by providing alternate documents, for instance, photocopies of Aadhar card application. Finally, Government appointed/approved female workers, e.g. Anganwadi workers, could hold community level events, and undertake carefully chosen door-to-door visits, to provide clarity on the currency exchange rules and assure women that their savings would remain safe.

3. Increasing use of mobile wallets amongst women: Studies have shown that mobile wallets (e.g. M-Pesa) have resulted in significant gains for women across Africa. They enable women to save securely, instead of living in the constant fear of it being stolen or misused by their male relatives. Further, their overall level of savings has been found to increase, as petty cash is not physically around for use. In addition, due to this money being part of a formal saving system, it can be used as collateral to raise loans to start small businesses.

Mobile wallet operators (MWOs) have already been marketing their services quite aggressively in the informal urban sector in India, with uptake seeing an increase in the past few days. To harness this momentum, MWOs could partner with NGOs, and micro-lenders to increase uptake amongst women, e.g. microloans could be disbursed through wallets. However, to achieve greater success, MWOs would need to a) ensure that both the buyer and seller side has access to its services – which in turn entails greater number of exclusive partnerships at retail level, and b) facilitate SMS-based transactions on feature phones.

The government could also support this endeavor by mandating that sellers provide at least one other option to cash for transactions.

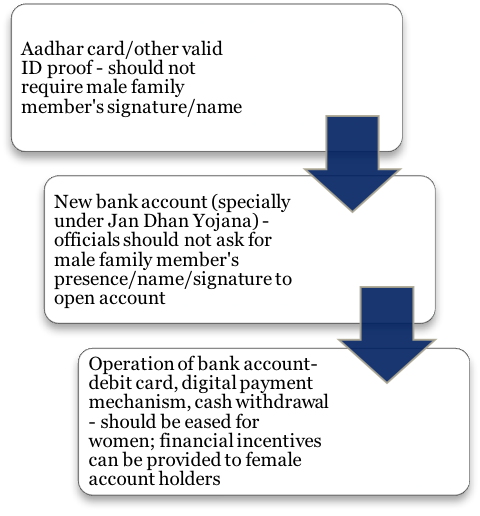

4. Ease access to banking for women: As shown in the figure, right from opening to making regular transactions, systemic changes are needed to ease women’s access to banks. Specific guidelines may need to be issued by the central government to sensitise bankers about not questioning women about male relatives. Further, banks could use the opportunity presented by the currency demonetisation to go to the doorstep of their potential female customer, and encourage more housewives, female informal workers and other segments of unbanked women to move into the formal banking system. In addition, they could also offer financial incentives, for instance, offering nominally higher interest rates for accounts held in women’s name, with central/ state governments supporting through policy action.

5. Change attitudes amongst women: State governments, urban local bodies and village panchayats could forge long term partnerships with NGOs to educate women on why they should, and how they can, make greater use of non-cash based payment methods, by working on changing mindsets and reducing attachment to physical cash.

In conclusion, it is incumbent upon the government to take note of women’s role in society, and their specifc constraints, and address them through simple, practical steps to ensure they are not left out in this period of transition.

This blog post was originally published on the LSE South Asia blog.