Creating a nation-state, and an economy, in South Sudan

South Sudan is in the news again. Conflict has flared up and we are reminded that political problems and ethnic tension are never the causes of anything. Rather, they are the predictable effects of dysfunctional economies and incoherent governance. Civil conflict arises and persists when young males cannot find superior livelihood prospects. Predatory behavior is an expected response to material want and unwanted leisure.

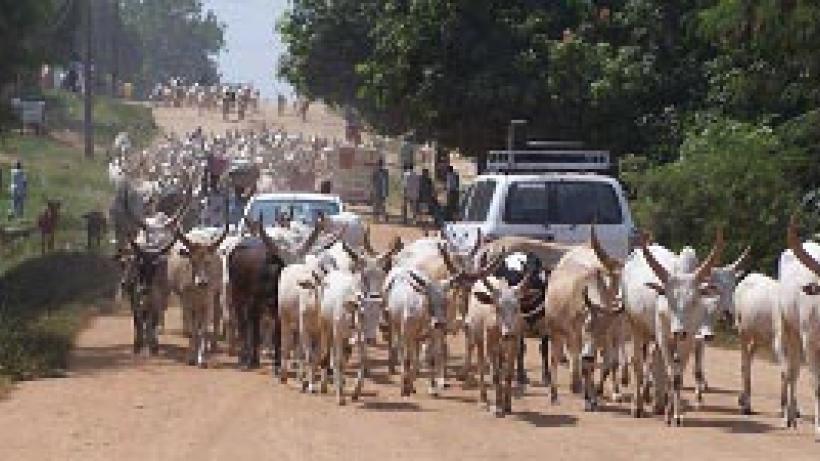

The international community claims that it is dedicated to fighting poverty. South Sudan is the perfect example of why that mandate cannot work. The problem in South Sudan is not that people are poor. Of course they are. A proper diagnosis reveals that there is no economic system in South Sudan. There is barely an exchange economy beyond the boundary of villages and towns. Unlike an economy dominated by grains and vegetables—all coming to market at somewhat regular intervals—a pastoral economy is characterised by low “transaction velocity.” Limited liquidity is tied up in animals and daily life entails minimal subsistence. In a post-conflict setting, scant economic activity occurs in isolated autarkic enclaves trapped in a low-level equilibrium from which there is no plausible escape. Programmes to “fight poverty” are inappropriate because they address symptoms not causes. South Sudan needs a development programme predicated on a coherent causal model. South Sudan is not a failed state, nor is it a fragile state. South Sudan is not yet a state. We must see it as a notional or aspirational state.

If South Sudan is to be rescued from dysfunction and incoherence, the international community must help to create the two essential institutions of governance. The first category concerns the legal foundations of a market economy. This legal foundation must be created by the South Sudan parliament, it must be justified to the citizenry, and it must become part of the necessary institutional scaffolding of a nascent market economy. The second class of necessary institutions concerns the pathways and protocols by which citizens are able to interact with government officials—both elected and civil service—on a range of issues that affect their daily life. These pathways and protocols allow citizens to have access to official organisations and their staff so that new problems are recognised and possible remedies introduced. These pathways and protocols give citizens “voice.” With those two institutional preconditions in place, the necessary development initiatives could be staged as follows:

Year One:

- Local Development Councils (LDC): There should be 10-15 designated development nodes encompassing the largest towns in South Sudan. These nodes would create Local Development Councils (LDCs) who would be responsible for mobilising citizens to identify local governance deficiencies in need of urgent improvement—schools, new water and sanitation services, enhanced teacher contracts, rural health clinics, agricultural extension services, etc. Each LDC could apply to a new Resource Revenue Council (RRC) that would distribute small grants to launch local development initiatives. The RRC would use oil revenues for these local efforts;

- Youth Employment Scheme (YES): Local Development Councils should launch and administer Youth Employment Schemes in each development node. The purpose of this initiative is to instill in the youth of South Sudan a commitment to their local community. Participation must be a great honour and so there should be a limited number of spots available in each development node. These young people would work after school, on weekends, and during school recess. The YES corps would carry out simple and routine tasks of great visibility in the local community. Participant should wear bright T-shirts in the colors of the South Sudan flag with the letters “YES” in bold colours. They would receive a small wage from the government which would be paid to their mother or some responsible female member of their household.

With these two civic engagement initiatives under way, it would be time to turn attention to the creation of a coherent economy. Three initiatives figure prominently here.

Year Two:

- Revitalised Pastoralism Systems: The livestock industry is the most important agricultural activity in South Sudan. Modest investments, careful restoration of the key institutional arrangements pertaining to grazing land and access to water, and carefully targeted extension programs on animal health and marketing will yield important economic dividends for pastoralist communities and the towns and villages that serve them.

- Town-Village Farming Systems: The development of localised farming systems will require a government commitment to an agricultural research program, to the creation of an agricultural extension service, to strengthening vocational agricultural programs in conjunction with schools and institutes, and to the full array of related services associated with a viable agricultural sector.

- Express Truck Fleet: The major transport corridors of Africa are lined with slow, overloaded, second-hand cargo trucks from Western Europe. The large trucks are not just highway hazards—they are destructive of roads and bridges. During the rainy season they become marooned in washed-out detours, and stranded along the side of the road. A better alternative would be a fleet of small light vans. A government loan program would allow individuals to purchase suitable trucks and establish a base in each of the development nodes. These new entrepreneurs would also participate in the creation and operation of a new freight logistical system. One hundred such trucks based and operating in the development nodes would offer a much-improved transport system for most of what needs moving around in South Sudan.

With these economic initiatives launched in Year 2, it would be time to turn attention to the final three initiatives. The first would augment and build upon the initiatives launched in Year Two, and the other two initiatives would focus attention on developing the human resources in South Sudan.

Year Three:

- Contract Farming Schemes: Contract farming offers potentially large employment and income gains. The most appropriate models might be those in which standardised contracting protocols are used in export-oriented agricultural operations elsewhere in North and East Africa.

- Future Professionals Programme (FPP): The civil service in South Sudan is hampered by a shortage of well-trained staff to carry out the necessary functions of governance. An FPP would enable college juniors and seniors to gain experience in the public sector. There would be a very selective probation period and only the very best participants would be offered permanent positions. Skills that should be especially recruited would include accountancy, business management, finance, human resources, pre-law, to name but a few.

- Civic Redeployment Programme (CRP): The CRP would provide an exit strategy for members of the army who are prepared to return to their home town or village and make a commitment to civic works determined by the Local Development Councils. These re-deployed soldiers would continue to receive a portion of their military pay, but would be gradually moved into other paying jobs in their home town or village. This transition period might be for a period of 3-5 years.

Oil is an exhaustible resource, and South Sudan will liquidate its stock in approximately two decades. Oil revenue over this very short period must be dedicated to the creation of the economic institutions of a coherent nation-state. There is no more urgent imperative, nor is there any time to waste.