Credit bureaus in microfinance: A baseline study

Credit bureaus consolidate borrowers’ creditworthiness records and share them with microfinance institutions, thereby addressing adverse selection and moral hazard problems. Such changes give safe borrowers lower interest rates but can lock those with poor or non-existent credit histories out of the market. Ongoing research in Pakistan investigates this trade-off.

For at least 30 years, the microfinance movement has sought to provide credit in settings where strong constraints mean traditional banking methods are inapplicable. One particular constraint — the high fixed costs of information gathering, storage, and dissemination — led to a group lending model in which lenders use information held by peers. This constraint has relaxed over time because microfinance institutions (MFIs) have grown, information technology has become less costly, and client incomes have risen. It is now possible to gather and store clients’ borrowing records and personal details in a credit bureau accessible by all MFIs.

Should the credit bureau strategy be embraced, and, if so, how should it be applied? The answer is not obvious, as it depends on competition among MFIs and the extent of hidden information, which drives adverse selection and moral hazard.

Tackling adverse selection

Without a credit bureau, adverse selection takes hold because lenders cannot discern borrowers’ risk types, so they charge higher interest rates to all. With no information sharing among MFIs, a MFI that succeeds in being repaid by certain borrowers is effectively a monopoly lender to the clients who have proven their creditworthiness. This dynamic has a negative effect because good clients end up paying more due to a lack of competition.

Over time, however, profits earned from high-quality borrowers mean that MFIs have an incentive to learn whether a client is a good prospect by offering small loans and observing repayment over time. The introduction of a credit bureau likely weakens both the positive and negative impacts; the overall implications for welfare depend on the extent of hidden information and the strength of competition in the market. Banks’ reliance on credit scores in developed countries allows individuals with good credit scores to change between banks but can make it hard for young people to get on the credit ladder.

Preventing moral hazard

Credit bureaus have similar opposing effects via curtailing moral hazard. Moral hazard in this case means that, upon receiving a loan, borrowers can then decide the amount of risk to undertake and whether they are willing to repay. Without information sharing between MFIs, individuals can default serially by moving between MFIs and hiding their debts.

On the positive side, information sharing means that default can be punished more effectively. Clients who default will likely be barred from all lending, rather than being able to start again at a different MFI. This will potentially allow for credit expansion, a win for both clients and lenders. On the negative side, some borrowers will default through no fault of their own, and an efficient lending system would allow for some form of credit score rehabilitation to return good but unlucky borrowers to the market. This may not be possible with a credit bureau if all lenders apply strict standards. The impacts on client welfare will be determined by the extent of moral hazard and how firms use the information in the bureau.

New experimental evidence to come from Pakistan

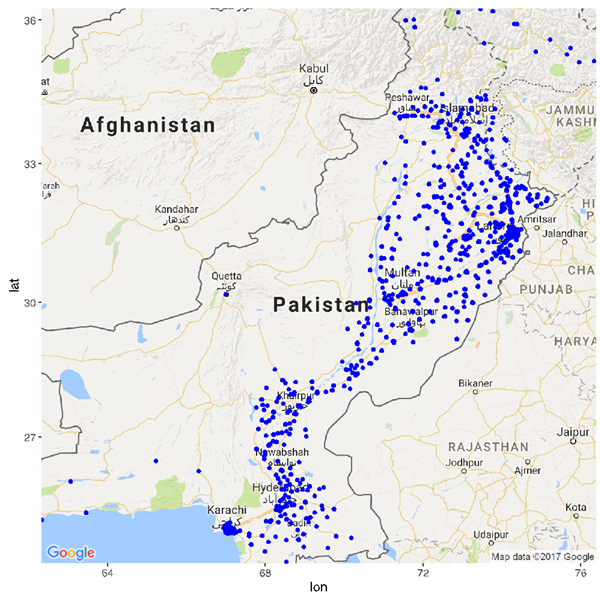

Pakistan recently launched a microfinance credit bureau. Figure 1 shows the distribution of MFI branches across Pakistan. Working with the Pakistan Microfinance Network, we have designed an experiment to evaluate the credit bureau’s impact.

Figure 1: locations of MFI branches in Pakistan

We have clustered these firms into different “markets” of competing branches and assigned each market to one of two randomly selected treatments. For some markets, all firms will have access to the bureau as soon as possible; other markets will have delayed access. We implement the design by sequencing the training of MFI staff on the new system. Using administrative data from the bureau itself, we will track how lending and borrowing behaviour is affected by the roll out. This experiment will permit us to assess how the bureau affects access to credit and the price of credit. We will also be able to study how variation in take-up changes the impact of the bureau.