From moving vehicles to moving people: Designing a mass public transportation system for Kampala

In developing countries like Uganda, urbanisation holds the key to achieving productivity and is therefore the foundation for economic growth.

Urbanisation is able to spur productivity by supporting the shift of workers from low productivity sectors and jobs in agriculture, to higher productivity jobs in manufacturing. The ability of urbanisation to foster a ‘productivity miracle’ is the reason why, to date, no country has developed without urbanising.

Figure 1: Kampala

Figure 1: Kampala

In order for urbanisation to result in productivity gains, a city must achieve a high degree of connectivity, which is the process that supports scale and specialization

In order for urbanisation to result in productivity gains, a city must achieve a high degree of connectivity, which is the process that supports scale and specialization. Cities enable efficient matching between particular skill sets and the labour market as well as between consumer demand and producer supply of goods and services. This is the process by which urbanisation has spurred economic growth in many developed countries.

African cities are urbanising at an unprecedented rate. However, many, like Kampala the capital city of Uganda, are doing so without achieving the commensurate gains in productivity. Rather, these cities are growing in a haphazard, unplanned fashion resulting in many challenges, such as the formation of slums, pollution and most notably, high degrees of congestion.

This article examines the challenge of congestion and potential proposed solutions in the form of mass public transportation systems from the perspective of Kampala, which is the largest city in Uganda and the backbone of the economy, generating over 60% of Uganda's GDP. It is also one of the fastest growing cities in the world, set to triple in size by 2050.

To date, Kampala has not had any mass public transportation system. Instead the majority of people commute either on foot or via low capacity transportation modes, including private vehicles. This has led to extreme traffic jams, and large losses in productivity. As part of its planning for future growth, Kampala needs to increase the speed and efficiency of the flow of people in the city. Accordingly, it is now looking at introducing a public transportation system and in this context is evaluating various transport alternatives.

Kampala: what’s feasible?

Kampala was originally intended to support a population of only 150,000 people. Currently, the estimated resident population is 1.5 million, with a daytime population of over 4.5 million people. Despite it being the capital city, it has not had any substantial city planning in the past; grossly underestimating the effects of future population growth as well as the interaction between transport networks and land use planning.

Figure 2: Kampala city planning

Figure 2: Kampala city planning

Today, there is a Kampala Physical Development Plan (KPDP), which is a comprehensive, long-term framework for the city. Building on the KPDP, the authorities are considering how to develop mass public transportation for the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area (GKMA). In this context, they have commissioned a series of feasibility studies to comprehensively analyse the current modes of transport used in the city as well as to evaluate different options for the future.

Current forms of transportation

The primary form of transport in Kampala is walking. It is estimated that up to 70% of urban dwellers commute by foot, with over 50% coming from a low-income-earning bracket. Walking, which has benefits such as being environmentally friendly, is not efficient in connecting people to jobs.

The primary form of transport in Kampala is walking

Aside from walking, the most common form of public transportation are matatus (Figure 3), which are 14-seater mini bus vans. In a transportation census conducted in 2013, it was estimated that there are 16,000 matatus in the city.

Figure 3: matatus

Figure 3: matatus

The next most common form of transport are boda-bodas (Figure 4), which are motorcycle taxis. There are currently estimated to be over 100,000 boda-bodas in Kampala. Although boda-bodas are a practical form of transport to avoid the delays associated with congestion, they are low capacity, carrying only up to two persons, as well as being notoriously dangerous, accounting for a major portion of the traffic accidents in the city.

Figure 4: boda-bodas

Figure 4: boda-bodas

The final major form of transport are approximately 400,000 private vehicles, which too are low capacity forms of transport and serve as the leading cause of the major traffic jams in the city.

Future options for mass public transportation

To date, the focus has been on rehabilitating, upgrading and expanding the road network. Currently, only 20% of the roads are in a fair condition.

Figure 5: Kampala roads

Figure 5: Kampala roads

Three options for mass public transportation have been under discussion: a bus rapid transit (BRT) system, a light rail train (LRT) and a cable car.

1.The bus rapid transit (BRT) system

Kampala is looking at becoming the fifth city in Africa to implement a BRT system. If well designed, the business case for a BRT is strong. In particular, examples from other cities have shown that most well-functioning traffic lanes can accommodate passengers up to 10 times the number of cars can per hour. Furthermore, it is a system that can be relatively cheap to build, if the necessary lanes are already available and run, with a minimum fare subsidy.

Figure 6: buses

Figure 6: buses

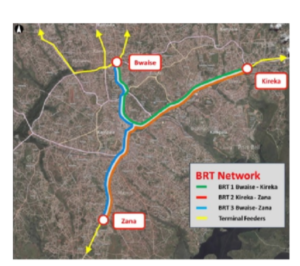

A feasibility study for the BRT system in Kampala, suggested a pilot that would travel on three routes between the areas of Bwaise, Kireka and Zana (Figure 7). This route has also been chosen to intersect with the non-motorized transport corridor planned for the city centre. It would allow commuters to terminate their travels on foot or by bicycle and thereby support a climate friendly transport service. The study also estimated the service could transport more than 37,000 passengers per day.

Figure 7: BRT system

Figure 7: BRT system

BRT obstacles

In cities with existing road and transport infrastructure to accommodate a BRT, the initial setup costs can be low. In Kampala, setup costs will be high for a number of reasons. The primary one is the complicated land tenure system in Kampala coupled with a lack of an updated land registry, which makes the purchase and development of land both difficult and expensive. Consequently, the majority of the cost of implementing a BRT system will come from having to pay for purchasing and compensating for land.

In Kampala, setup costs will be high for a number of reasons. The primary one is the complicated land tenure system in Kampala coupled with a lack of an updated land registry, that makes the purchase of land both difficult and extremely expensive

Furthermore, Kampala does not have an existing expansive public bus system in place. Over the past decades there have been a variety of private buses that have tried to establish themselves, but have subsequently gone bankrupt. Therefore, an upfront capital investment will have to be made in a more expansive bus system to feed into the BRT routes.

The final major cost is the need to restructure and expand the road network. For a BRT system, it is important to have and also enforce lanes that are solely dedicated to buses. Taking into account these obstacles, the pilot routes for the BRT could cost over 400 million USD to build.

Taking into account these obstacles, the pilot routes for the BRT are expected to cost over 400 million USD to build

2. The light rail transit (LRT) system

An alternative to the BRT system is the LRT system. Generally, 'light rail' is used to describe systems that are somewhere in the middle of the passenger train spectrum in terms of passenger capacity and speed. The only one operating in Sub-Saharan Africa to date is the LRT that opened in September 2015 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Figure 8). It is partly what inspired Kampala to consider its own LRT.

LRT systems are considered an environmentally clean technology and more efficient than the BRT as it can carry more passengers per hour. It is also a suitable technology for a city like Kampala, with its hilly topography, as it can perform on steep gradients and sharp curves.

Figure 8: LRT system in Addis Ababa

Figure 8: LRT system in Addis Ababa

The feasibility study of a potential LRT system is only in its initial stages and therefore, there is no concrete outlines available yet. However, the idea is that when completed, the Kampala LRT system could comprise of 70-80km of lines. Based on cost estimates from Addis Ababa, the expectation is that the cost of construction of an LRT in Kampala would be significantly higher than the BRT.

3. The cable car

A cable car is seen as an obvious option to overcome the challenge of congestion given that it entirely avoids the roads. Furthermore, given Kampala's hilly topography, the cable car has additional benefits. A cable car could attract tourists to Kampala and thus support the aim of expanding tourism. However, this would not be the main purpose of the technology.

Figure 9: cable cars

Figure 9: cable cars

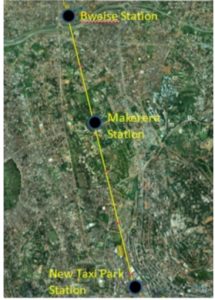

The current pilot line for the cable car has been proposed to run from the outskirts of the city and terminate in the centre of the city (Figure 10). The initial route would be approximately 4 kilometres long and potentially have cheaper upfront costs than the BRT and LRT, due to the fact that it avoids having to pay compensation for the land. Therefore, the expected total cost for the construction could be around the quarter of what the BRT system would cost.

Figure 10: pilot line for the cable line

Figure 10: pilot line for the cable line

However, a large determinant of the cost structure in this context would be the technology, which is likely to be imported. Furthermore, although the cable car does not require as much land as a BRT or an LRT, there will still be significant costs in terms of land acquisition for the stations and the pylons, depending on which route is selected.

The initial route would be 4.6 kilometres long and potentially have cheaper upfront costs than the BRT and LRT, due to the fact that it avoids having to pay compensation for the land

At its peak, the estimate for cable car travel, based on a mono-cable system, is 3000 people per hour, distributed across 8 people per cabin in 99 cabins. Based on this, annual revenues could be to be high, depending what ticketing prices are selected. Additionally, as this is classified as a clean technology, there may be the opportunity to receive income from carbon credits too. However, appropriate pricing of tickets will also be a challenge and will likely have to be subsidized to make them affordable to the majority of the population.

Finally, cable cars would have to be integrated into an overall mass public transportation system that can get people to and from the cable car station. Therefore, although heralded as a modern technology, the cable car may not be suitable for a city the size of Kampala, that needs to concentrate on establishing the main arms of a mass public transportation system first.

From moving vehicles to moving people

Introducing a public transportation system would go a long way to alleviating congestion and solving the connectivity challenge in Kampala. As outlined by the various feasibility studies, the BRT, LRT system and cable car all present both opportunities in terms of alleviating congestion but also a variety of challenges, most notably in terms of the cost of introducing each technology, as well as administrative costs.

As outlined by the various feasibility studies, the BRT, LRT system and cable car all present both opportunities in terms of alleviating congestion but also a variety of challenges, most notably in terms of the cost of introducing each technology, as well as administrative costs

Based on the limited experiences from other developing countries who have introduced these technologies, the BRT does seem like it would be the most feasible and desirable as it seems to be the lowest cost technology per volume of passengers. Furthermore, although there will be a large upfront cost in acquiring the land, in this context it could be a worthwhile anchor investment to support the further efficient spatial growth of the city. To support or refute this conclusion, more research and in particular cost-benefit analyses will need to be done into all options and at a later stage into the relevant routings to ensure that whatever mass public transport system is introduced, it has the highest impact on alleviating congestion. However, notwithstanding this, it is imperative that Kampala and the GKMA introduce a public transportation system as soon as possible.

This piece has been cross-posted on the Innovative Governance of Large Urban Systems' blog.