Beyond borders: Making transport work for African trade

Africa has seen massive trade liberalisation in the last three decades. But the success of translating reduced tariffs into increased international trade has been limited and geographically unbalanced. One of the main reasons for this is the high cost of moving goods within countries.

While the rest of the developing world has been tapping into global value chains and raising international exports, African trade has, on average, stagnated and in some cases even regressed. This has happened despite a big reduction in tariffs, global logistic charges, and other factors affecting the cost of trading internationally.

One of the potential explanations for this stagnation is that intra-national trade costs remain substantially high in many countries in Africa. These costs are incurred both when transporting goods over long distances, and when clearing the goods at harbours or border controls. The costs then have a knock-on effect on the total volume and efficiency of international trade with other countries.

This growth brief looks at the cost of transporting goods across Africa and suggests that the reduction of trade costs could increase gains from globalisation to remote areas and help tackle regional inequality.

-

TransportGrowthBrief_FINAL_WEB.pdf

PDF document • 592.36 KB

Introduction

Recent research shows that these costs constitute a significant barrier to trade in many countries. Atkin and Donaldson (2015) have shown that while the low availability and quality of roads is a well-recognised factor, inefficient logistics, low vehicle quality, and policies restricting competition also have significant effects.

Reducing these costs would increase trade and improve economic performance for exporting firms in Africa.

Key messages

- The high cost of getting goods to and from borders or ports in Africa is restricting the continent’s potential gains from international trade.

Despite increasing global efficiencies, the cost of moving goods domestically remains high and can be up to five times higher in Africa than in the US. This

acts as a severe barrier to trade and limits the economic benefits globalisation may bring. - Poor roads increase the cost of transporting goods over long distances, but other factors may also be significant.

The market power of logistics companies, delays at border controls, customs regulations, and low-tech transport vehicles are key factors affecting trade costs. - Reducing trade costs could spread the gains from globalisation to remote areas and help tackle regional inequality.

The high costs of intra-national trade (trade within a country) mean that remote locations benefit less from trade liberalisation and the lower prices and market opportunities it brings.

Key message 1 – The high cost of getting goods to and from borders or ports in Africa is restricting the continent’s potential gains from international trade.

The costs of moving goods within countries are generally higher in developing countries than in the rest of the world, and this is especially true in much of Africa. Transport in Africa is often unpredictable and unreliable, and the cost of transport is therefore often higher than the value of the goods being transported (World Bank, 2007).

In some areas of Africa, transport costs may constitute a higher trade barrier than import tariffs or other trade restrictions (Amjadi and Yeats, 1995). A one-day reduction in inland travel times could lead to a 7% increase in exports – equivalent to a cut of 1.5 percentage points on all importing-country tariffs (Freund and Rocha, 2010). It has also been estimated that a 10% drop in transport costs could increase trade by 25% (Limao and Venables, 2001).

It is difficult to give an exact estimate of the size and implications of existing transport costs in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in environments where data is scarce. Various techniques have been used (see box on pg. 3), with one study estimating that the unit costs of road transport are 40–100% higher in Africa than in Southeast Asia (Rizet and Gwet, 1998). In landlocked countries, estimates suggest the costs are three to four times higher than in other developed countries (MacKellar et al., 2002).

However, more recent research suggests these could be substantial underestimates. Atkin and Donaldson (2015) reckon that the cost of transporting goods could be up to five times higher (per unit distance) in some sub-Saharan African countries than in the US. In the case of Ethiopia, the “cost of distance” is estimated to be about 3.5 times higher relative to the US, while in Nigeria, it is 5.3 times higher.

Atkin and Donaldson (2015) reckon that the cost of transporting goods could be up to five times higher (per unit distance) in some sub-Saharan African countries than in the US.

There is little doubt that such relatively high costs would put upward pressure on the prices of a country’s imports, and simultaneously make its exports less competitive in international markets – and that both of these factors would act to reduce the country’s level of international trade.

Having an accurate estimate of transportation costs is important in order to understand the role these costs play in determining the overall level and benefits of international trade. These new estimates suggest that the beneficial effect of reducing transport costs could be even larger than previously thought.

Calculating the cost of distance

Estimating the size of intra-national trade costs and how these costs depend on distance proves challenging. Many studies have tried to do this by using the quoted price of transport from trucking surveys (see for example, Rizet and Gwet, 1998). Although such quotes can give an approximate measure of trade costs, they only capture the components that transport firms charge, omitting other costs of distance (delay, uncertainty, risk of damage or theft, difficulties of buyers and sellers matching and monitoring one another, etc.)

The most straightforward way to estimate the cost of distance without using surveys would be to calculate the difference in price of an imported good when sold at the port of origin versus the price at the destination. This requires detailed data on goods, with specific information about their origin and price at different locations. This is necessary to ensure that the goods sold at different locations are identical, and that price differences do not simply reflect differences in quality. Atkin and Donaldson (2015) generate a unique dataset to tackle this challenge, where the prices of goods are recorded at the barcode-equivalent level and also include information on its origin and destination.

Once such data has been found, the calculation still presents a serious challenge, as the difference in price between origin and destination may reflect not only the desired intra-national trade costs but also an added mark-up by traders, which may vary across locations.

To address this problem, Atkin and Donaldson (2015) remove the variation in mark-ups from the data on prices. They do this by observing how a change in price (perhaps due to a reduced tariff or a change in production costs) at the port or source location is reflected in the price of that good at the destination – the so-called pass-through rate. Using this information, the authors can deduce how strongly mark-ups are affected by transport costs and are thus able to arrive at a clean estimate of the intra-national trade costs.

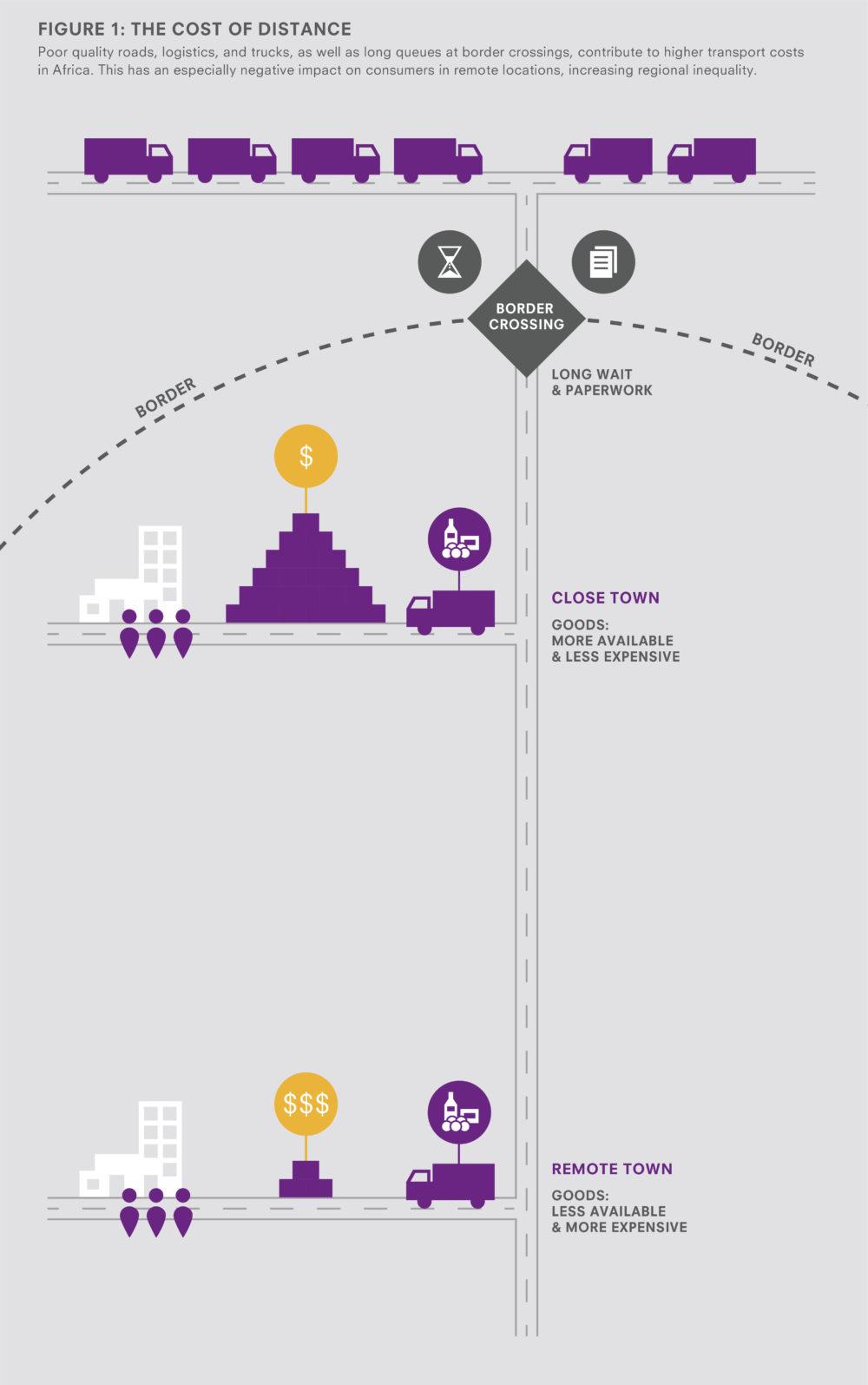

Figure 1: The cost of distance

Poor quality roads, logistics, and trucks, as well as long queues at border crossings, contribute to higher transport costs in Africa. This has an especially negative impact on consumers in remote locations, increasing regional inequality.

Key message 2 – Poor roads increase the cost of transporting goods over long distances, but other factors may be more significant.

Africa’s infrastructure is improving but it is doing so from a low base. Poor-quality roads and weak transport infrastructure have long been an issue for African trade, and are considered prime reasons for the continent’s low level of competitiveness. The large majority of roads in sub-Saharan Africa are poorly maintained and a significant number – around 53% – remain unpaved (The African Development Bank, 2014).

Although it is tempting to attribute the majority of Africa’s high trade costs to poor road quality, research shows that this may not necessarily be the main determinant of high internal transport costs. Instead, research finds that the high burden of distance between typical cities in Ethiopia and Nigeria remains, even after adjusting for the availability and quality of roads (Atkin and Donaldson, 2015).

Even when taking into account that there are both more and better quality roads in the US, the cost of distance is still 2.5 times higher in Ethiopia and four times higher in Nigeria than in America. This is a surprising finding: with its low wage levels, Africa’s transport costs should be much lower than in the US if roads were of the same quality, since the trucking industry is so labour-intensive.

There remain a wide range of factors that could generate high intra-national trade costs within African countries: the price of inputs such as fuel, labour, and equipment on the one hand; and market characteristics, including regulations, transport, and trade procedures on the other.

Among potential logistics costs are market-entry barriers such as access restrictions, technical regulations, customs regulations, and cartels (Teravaninthorn and Raballand, 2009). Corruption and protectionism may serve as a barrier to entry for modern or more efficient logistics firms. In addition, many routes are under-utilised and trucks often travel short distances, or only carry a small load. As a result, potential economies of scale are not captured and internal transport prices remain high.

Other factors affecting intra-national trade costs are long waiting times for loading or unloading, and frequent checkpoints. On average, in 2006, it took 116 days to move an export container from the factory in Bangui, Central African Republic, to the nearest port and fulfil all the customs, administrative, and port requirements to load the cargo onto a ship (OECD/WTO, 2011).

Even though the required number of days has been falling, exporters and importers require 50% more time to get exports to market in Africa than in East Asia. Reducing such delays could have a dramatically positive effect on export volumes (Arvis et al., 2014). Lastly, inferior technology, for example old truck fleets that are fuel-inefficient, may severely increase the cost of intra-national trade (Atkin and Donaldson, 2015).

Even though the required number of days has been falling, exporters and importers require 50% more time to get exports to market in Africa than in East Asia.

It has often been presumed that large investments in improved road infrastructure would reduce transport prices, but this does not appear to have been the case. The significant support programmes implemented by the World Bank since the 1970s in transport corridors in Africa has had little if any impact on transport prices (Teravaninthorn and Raballand, 2009).

Once roads are paved, further improvements have not been found to result in a significant reduction in transport costs (Teravaninthorn and Raballand, 2009). Instead, to be successful, policies need to recognise the complexity and diversity of high intra-national trade costs and address a wider range of infrastructure constraints such as those highlighted above.

Country case studies: The ease of trading across borders

Rwanda

Some progress has been made in eliminating the costs of trading across borders in Rwanda, partly through the removal of non-tariff barriers in the East African Community (EAC), but more needs to be done. In 2015, Rwanda scored very low on the World Bank’s Doing Business indicator for “trading across borders”, which indicates the time and cost of documentary and border compliance. This was partly due to a policy requiring a pre-shipment inspection for all imported products. A reversal of this policy in 2016, combined with the introduction of an electronic single-window system at the border, improved Rwanda’s rank from 131st in 2015 to 87th in 2016.

Rwanda now does better than the sub-Saharan African average and its East African neighbours, especially in terms of cost. However, as Rwanda is separated from its nearest port by 1,500 km, there are still significant challenges when it comes to the costs of internal trading.

Uganda

Uganda ranks almost at the bottom of the quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure component of the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI), far below the sub-Saharan African average and other comparable landlocked sub-Saharan African countries. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators, border compliance in Uganda takes 71 hours for exports, and 154 hours for imports.

Although Uganda’s performance is not dramatically worse than that of its regional peers, it clearly hampers the ability of firms to move goods across borders in a globally competitive way. Moreover, only 17% of Uganda’s national roads are paved, only about 25% of the country’s railway network is operational, and it only has one international airport. Difficulties with road transport in Uganda may cause particular problems in getting agricultural goods to market, and minimising post-harvest loss.

Kenya

Kenya currently ranks 105th on the World Bank’s Doing Business indicator with regards to ‘trading across borders’ and has seen no progress in the last five years. Although it has improved tremendously since 2007, Kenya is still experiencing serious challenges on the logistics side of trade facilitation, as evidenced by its rank of 74th in the 2014 LPI. Another area of concern is inadequate road infrastructure.

Due to the extensive documentation requirements, customs processing delays, and non-transparent importing rules, import and export procedures are also very costly and time-consuming. The capacity of domestic institutions responsible for ensuring compliance with international standards is limited. Moreover, local standards vary greatly and there is little harmonisation with regional or international standards.

Figure 2: The ease of trading across borders

Key message 3 – Reducing trade costs could spread the gains from trade to remote areas and help tackle regional inequality.

Internal trade barriers not only hinder trade and dampen economic growth, they also distort the benefits of globalisation and increased trade. As tariffs fall and international transportation improves, the benefits from the consequent price changes may not accrue to all consumers equally. Remote locations are generally harmed more by the burdens of intra-national trade costs than areas close to borders or ports. This limits the benefits of globalisation in remote villages or rural settlements (World Trade Organization, 2004). High intra-national trade affects consumers in remote areas in two key ways. Firstly, with a high price of transportation to remote areas, consumers in remote locations may be less likely to buy foreign goods. This could be either because the goods are too costly or because they are not available in the first place (Atkin and Donaldson, 2015).

High intra-national trade affects consumers in remote areas in two key ways. Firstly, with a high price of transportation to remote areas, consumers in remote locations may be less likely to buy foreign goods. This could be either because the goods are too costly or because they are not available in the first place (Atkin and Donaldson, 2015).

Secondly, Atkin and Donaldson (2015) find that even when foreign goods are available in remote areas, consumers in those places benefit less from a reduction in the international price of imports. Instead, the reduction in price benefits the producer or intermediaries more than the consumers. This is because the high cost of transporting goods within a country appears to make retail and distribution activity less competitive in remote areas relative to urban areas. As such, if the origin price of an imported good falls, due to lower tariffs following globalisation for example, the price of that good does not fall as much in rural locations.

These findings suggest that increased globalisation exacerbates regional inequalities. As the cost of international trading falls, places closer to borders and ports benefit more than those in remote locations. Atkin and Donaldson (2015) conclude that reducing the cost of transporting goods could reduce regional inequality and specifically benefit families in rural settlements or remote villages.

Policy recommendations

- In order to boost sub-Saharan Africa’s participation in international trade, policies need to address the exceptionally high intra-national trade costs that increase the cost of transferring goods and resources throughout the country and to and from ports and borders.

- Policies aimed at reducing the costs of trade should not solely focus on improving the quality or availability of roads. Other factors need to be addressed, such as restricted market competition in logistics, inferior technology of transport vehicles, and under-utilisation of trucks and roads.

- It is important to address policies governing infrastructure, such as restrictions on competition, standards and licensing, and border inspections that reduce the efficiency of highways. Reducing delays at ports and border crossings is critical to improving the cost-efficiency of transport.

- Policies to reduce the high costs of intra-national trade to ensure a more equal distribution of the gains from globalisation should be implemented. Lower intra-national trade costs could lead to reduced regional inequalities and benefit economic growth in remote areas.

References

African Development Bank. (2014). Tracking Africa’s Progress in Figures. African Development Bank, Tunis.

Amjadi, A. and Yeats, A.J. (1995). Have Transport Costs Contributed to the Relative Decline of Sub-Saharan African Exports?. The World Bank, International Trade Division, Washington D.C.

Ansu, Y., McMillan, M., Page, P. and Willem Te Velde, D. (2016). ‘Promoting Manufacturing in Africa’. African Transformation Forum 2016.

Arvis, J.F., Saslavsky, D., Ojala, L., Shepherd, B., Busch, C. and Anasyua, R. (2014). Connecting to Compete 2014: Trade Logistics in the Global Economy. The World Bank. Washington, D.C.

Atkin, D. and Donaldson, D. (2015). Who’s Getting Globalized? The Size and Implications of Intra-national Trade Costs. NBER Working Paper No. 21439. Cambridge, MA.

Freund, C. and Rocha, N. (2010). What constrains Africa’s exports?. Staff working paper ERSD, No. 2010–07.

Limao, N. and Venables, A. J. (2001). ‘Infrastructure, Geographical Disadvantage and Transport Costs’. World Bank Economic Review 15 (3): 451–79.

MacKellar, L., Wörgötter, A. and Wörz, J. (2002). ‘Economic Growth of Landlocked Countries’. Ökonomie in Theorie und Praxis. Springer. Berlin.

OECD/WTO. (2011). Aid for Trade at a Glance 2011: Showing Result. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Rizet, C. and Gwet, H. (1998). ‘Transport de Marchandises: Une Comparaison Internationale des Prix du Camionnage – Afrique, Asie du Sud Est, Amérique Centrale’. Recherche–Transports–Sécurités 60: 68–88.

Teravaninthorn, S. and Raballand, G. (2009). Transport Prices and Costs in Africa. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank, Washington, D.C.

World Bank. (2007). Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. An Independent Evaluation Group Review of World Bank Assistance. The World Bank, Washington DC.

World Trade Organisation. (2004). “World Trade Report” pp. 114–148. World Trade Organization, Geneva.

Citation

Donaldson, D., Jinhage, A. and Verhoogen, E. (2017). Beyond borders: Making transport work for African trade. IGC Growth Brief Series 009. London: International Growth Centre.