Rewarding bureaucrats: Can incentives improve public sector performance?

This brief synthesises lessons from the latest research on strategies to improve the performance of public sector workers, including government administrators and frontline service providers, such as teachers and health workers. The focus is on strategies for recruiting and motivating the public sector workforce.

-

IGCJ5270_PublicSectorWorkersGrowthBrief_220317_WEB.pdf

PDF document • 448.1 KB

Introduction

Effective public service delivery in developing countries ultimately depends on the performance of public sector workers. What can governments do to recruit, motivate, and retain the best candidates? This brief explores the role for performance rewards to improve public service delivery.

Improving public sector performance is an important priority for many developing countries. Governments play a critical role in providing public goods needed to support economic growth, such as health, education, infrastructure, and property rights – and the effectiveness of these services crucially depends on the performance of the people who deliver them.

This brief synthesises lessons from the latest research on strategies to improve the performance of public sector workers, including government administrators and frontline service providers, such as teachers and health workers. The focus is on strategies for recruiting and motivating the public sector workforce.

Some of the fundamental challenges governments face include determining the right types of individuals to select for public sector jobs, finding effective ways to recruit these candidates, and motivating them to perform well on the job.

Governments often look for specific characteristics such as high intrinsic motivation, integrity, and relevant abilities which may predict better on-the job performance – but it can be difficult to identify the right characteristics during the hiring process, and long-term performance also depends on the job environment and incentives offered.

Offering incentives is one potential strategy to address both the aims of attracting stronger candidates and motivating better job performance in the public sector. This brief synthesises lessons from the latest research on strategies to improve the performance of public sector workers, including government administrators and frontline service providers, such as teachers and health workers. The focus is on strategies for recruiting and motivating the public sector workforce.

Key messages

-

Key differences between the public and private sectors pose unique challenges for improving government worker performance.

Strict rules often limit the options for hiring, firing, or offering benefits to workers in the public sector.

-

Well-designed financial rewards linked to job performance can help improve public sector outcomes.

This potential exists if performance can be accurately measured and there is clear understanding about how the financial incentives work.

-

Performance incentives can backfire – particularly where desired outcomes are broad or difficult to measure.

It is important to avoid focusing on measurable outcomes at the expense of other important but difficult-to-track goals.

-

Carefully designed non-financial incentives can also provide powerful and cost-effective strategies for motivating government workers.

Non-financial incentives such as social recognition may provide an effective solution.

-

Governments should focus more attention on recruiting more qualified, motivated staff in the first place.

Strategies such as offering higher salaries and opening up the recruitment process may help to raise the calibre of new hires and improve public sector performance.

Key message 1 – Key differences between the public and private sectors pose unique challenges for improving government worker performance.

There are several ways that employment and personnel practices in the public sector typically differ from those in the private sector due to the nature of the government’s objectives (Dixit, 2002; Finan et al., 2015). These features need to be considered when designing and implementing effective policies for recruiting and motivating government workers.1

First, the public sector has limited capability to offer employees certain types of benefits that private companies can offer, such as shareholdings to incentivise managers to maximise company performance. This also means that politicians and civil servants are less likely to be directly affected by poor performance, compared to managers who may experience financial losses from inefficiencies.

Second, governments often have rigid rules that restrict hiring and firing of civil servants. Civil service systems often use strict formulas that define criteria for hiring, compensation, and promotion compared to the private sector where there is usually more flexibility. These rules have often been designed to prevent politicians from exerting undue influence over civil servants, but they also tend to limit the government’s ability to incentivise performance.

Third, the fact that public sector organisations serve societal needs may draw different types of individuals into the public sector compared to the private sector, so it can be useful for personnel policies to take this into account. In particular, if these individuals are sufficiently motivated to work to the best of their abilities, offering performance pay will increase the government’s bill without improving performance.

Finally, public sector organisations often face limited competition in the services provided. Public services like health and education are often heavily subsidised and face limited competition from other providers. This lack of competition may translate into less pressure on employees and a greater need for monitoring as compared to the private sector, where competition helps to incentivise productivity and reduce inefficiency. While all the issues above may present some challenges for employee recruitment and management, with adequate attention, they need not inevitably limit public sector performance.

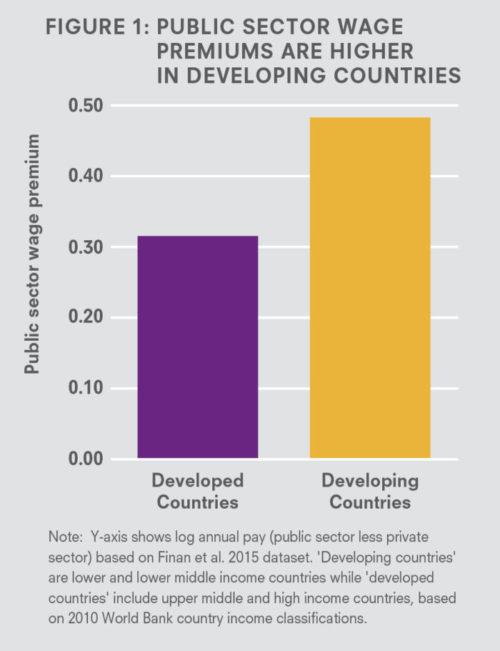

Interestingly, government workers in developing countries are usually paid much better than their private sector counterparts, but restrictive hiring, firing, and promotion rules often weaken performance. Figure 1 compares average wages of public and private sector employees in 39 countries using household survey data (Finan et al., 2015). In most countries, average salaries in the public sector are higher than in the private sector –and the pay gap is largest in poor countries where public sector workers earn more than twice as much as their private sector counterparts. After controlling for other factors such as location, age, and education, the public sector wage premium disappears for developed countries but remains significant for the poorest countries. Overall, the evidence suggests that poor government performance in developing countries is not simply due to government workers being underpaid.

Figure 1

Finan et al., 2015

Key message 2 – Well-designed financial rewards linked to job performance can help improve public sector outcomes

It is well known that performance-based incentives can help to motivate better behaviours from workers in the public sector just as in the private sector. In order to limit political influence over salaries, however, civil service salaries are typically based on rigid, formulaic pay scales with limited room for using financial incentives to reward performance. Nonetheless, governments are increasingly developing creative schemes to attract more qualified staff and motivate good behaviour based on outcomes achieved. In places where a large scale restructuring of government salary structures may be difficult, leveraging even just a small portion of the wage bill toward merit-based incentives may yield surprising results, particularly when performance can be accurately measured.

A number of studies have documented the impact of policy experiments that reward performance based on outcomes in areas including health, education, and public finance. Policy findings emerging from this research show that it is important to ensure that financial incentives are simple, well understood, and linked to clear, measurable targets.

Research on health centres in Rwanda suggests that offering performance-based pay to health facility staff might lead to improved provision of pre- and post-natal care (Basinga et al., 2011; Gertler and Vermeersch, 2012). A study in Indonesia found that offering incentive payments to villages based on their performance on a set of health indicators improved outcomes such as prenatal visits and malnutrition rates, although these effects became less significant over time (Olken, Onishi and Wong, 2014).

In the education sector, Muralidharan and Sundararaman (2011) examined a large-scale programme in India, where public school teachers’ pay was partly determined by student test scores. After two years, they found that the relatively small incentives – equal to 3% of teachers’ annual salaries on average – substantially improved student learning in math and language.

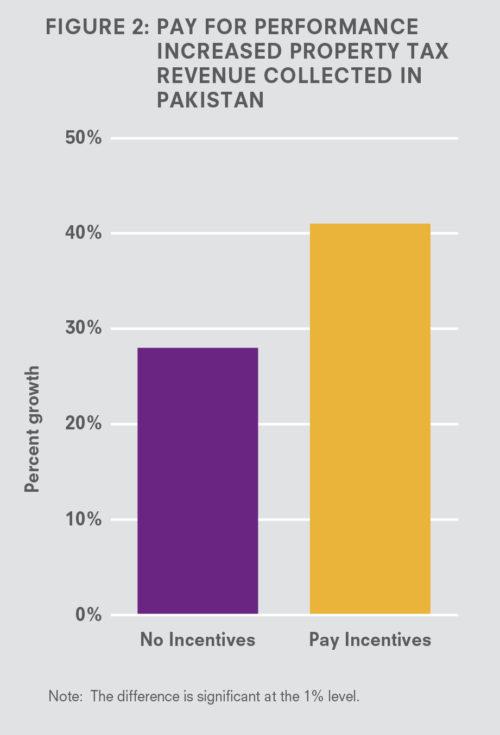

In the area of public finance, an IGC study by Khan, Khwaja and Olken (2014) found that offering incentive payments to tax collectors in Pakistan helped increase tax revenues – a major challenge for the government (See Figure 2). In areas where tax collectors were offered large incentives, revenue growth was 13 percentage points greater than in areas without incentives. Importantly, the intervention was cost-effective, with revenue gains significantly exceeding the cost of the incentives.

While a common fear is that incentives might ‘crowd out’ intrinsic motivation to get a job done well, there is in fact only limited empirical evidence to support this in practice. Instead, the latest evidence tends to suggest that incentives can in fact leverage intrinsic motivation (Ashraf et al., 2014; Rasul and Rogger, 2016).

Another key lesson underlying all of this work is the importance of putting into place strategies for measuring the results and cost-effectiveness of performance-based incentive schemes over time –including any unintended consequences – in order to continually inform policy decisions on whether these schemes should be dropped, adjusted, or scaled up.

Figure 2

Khan, Khwaja and Olken, 2014

Key message 3 – Performance incentives can backfire – particularly where desired outcomes are broad or difficult to measure

Performance pay is more appropriate and effective for jobs where the desired outcomes are easily defined and measurable. It is important for incentives to be linked to behaviours or outcomes within the scope of what workers can affect, and incentive schemes should be simple enough to be widely understood. When outcomes are harder to quantify or longer term in nature, performance incentives can lead public servants to focus too much on performing well on measurable outcomes at the expense of a broader range of important but more difficult-to-track goals.

Recent experiments illustrate some of these tradeoffs. One example is a randomised trial that rewarded some Kenyan teachers with in-kind prizes based on school-level performance on government exams (Glewwe, Illias and Kremer, 2010). The incentivised schools achieved higher scores on the government exam but did not score higher on a separately-administered independent exam. The researchers concluded that teachers may have increased emphasis on test-taking skills for the national exam rather than improving general instruction. Similarly, a policy change in the United States that allowed police agencies to keep revenues obtained from assets seized during drug arrests resulted in the police performing more drug arrests but reduced enforcement of other types of crimes (Baicker and Jacobson, 2007).

Research on the Nigerian civil service shows that incentives that reward ‘box ticking’ can reduce bureaucrats’ performance (Rasul and Rogger, 2013). However, in some cases, intermediate input measures can function as a proxy for outcomes – for instance, incentives for teachers may be based on teacher attendance rather than student learning because it is easier to monitor. One study in India found that teacher incentives based on attendance also increased learning (Duflo, Hanna and Ryan, 2012). In contrast, a similar study on financial incentives for nurses’ attendance in India found that incentives were not effective because the attendance reporting system was undermined over time (Banerjee, Glennerster and Duflo, 2008). In general, incentives can be based on inputs or outcomes depending on the nature of the task and how well the inputs or outcomes can be monitored.

An overall lesson is that incentives need to be pilot-tested and designed for each specific context, with care to avoid inadvertently incentivising perverse behaviours or ‘gaming the system’. A related challenge is how management practices can give greater autonomy and discretion to public sector workers in ways that motivate better performance rather than resulting in corruption or worse outcomes.

Photo credit: Getty Images | Keren Su

Key message 4 – Non-financial incentives can provide powerful and cost effective strategies for motivating government workers

Offering non-financial incentives can be an effective way for governments to motivate employees, particularly because rigid civil service pay scales may limit their ability to offer financial incentives. Non- financial incentives include rewarding high achievers through social recognition, leveraging career concerns through performance-based promotions or postings, or offering in-kind benefits such as subsidised housing.

Although it is quite common for governments to offer non-financial incentives, few of these schemes have been rigorously tested. One exception is an experimental study that directly compared the effectiveness of using non-financial versus financial incentives to motivate public health extension workers in Zambia to sell condoms for HIV prevention (Ashraf, Bandiera and Jack, 2014). Non-financial rewards proved to be surprisingly effective: agents who received social recognition for their sales (via earning stars on a thermometer-type display) achieved double the sales versus those earning a commission of up to 90% on condom sales.

Another example with promising results is a recent IGC evaluation of a performance-based postings scheme in Pakistan that gave tax collectors an opportunity to be transferred to more desirable locations depending on their performance on revenue collection (Khan, Khwaja and Olken, in progress).

Innovative non-financial incentive schemes have the potential to help governments raise performance in a cost-effective manner. There are also numerous examples of governments offering employees in-kind benefit programmes that are riddled with inefficiency so the justification for offering non-financial incentives over cash needs to be well-supported.

Key message 5 – Governments should focus more attention on recruiting more qualified, motivated staff in the first place

Often, governments focus too much on how to motivate their existing workforces and not enough on how to recruit the best job candidates in the first place. Hiring more qualified and intrinsically motivated workers to begin with is likely to go a long way toward raising overall public sector performance. Improved recruitment strategies and systems, along with offering performance-based incentives, have potential to help attract the right types of people.

Governments use different methods to recruit and screen applicants for public servant jobs. Some governments require civil servants to pass an exam or meet educational requirements like having a university degree, while others use approaches that allow more flexibility and discretion but may also be prone to corruption or patronage.

One clear finding from a large body of research in public administration is that public servants who have high levels of intrinsic motivation tend to perform better on the job (Boyne, G. A. et al., 2009; Perry and Hondeghem, 2008). This is further supported by a few experimental studies that find health workers who exhibit high levels of pro-social motivation achieve better outcomes (Ashraf, Bandiera and Jack, 2014; Dizon-Ross, Dupas and Robinson, 2014; Callen et al., 2014; Deserranno, 2014).2 However, intrinsic pro-social motivation tends to go along with other positive personality traits, and in practice, it is difficult for governments to select employees based on this characteristic. There is therefore room to identify creative strategies for governments to attract a more intrinsically motivated applicant pool in the first place.

Offering higher salaries is commonly used as a strategy for attracting better qualified new entrants to the public sector. Evidence shows that increasing salaries can help attract better employees who are not necessarily less pro-social or more corruptible. A field experiment by Dal Bó, Finan, and Rossi (2013) randomly assigns different wage levels during a drive to recruit community development workers and finds that higher wages help attract better quality applicants. In particular, the promise of a salary of 5,000 pesos per month instead of 3,750 pesos attracted smarter, more experienced candidates with higher previous earnings – and these applicants did not appear to be any less intrinsically motivated.

Along similar lines, an IGC-funded, randomised experiment on community healthcare workers hired by the Zambian government found that job advertisements with a ‘go-getter’ message emphasising the career promotion opportunities of the job – rather than a ‘do-gooder’ message emphasising the role’s potential to help the community – helped to attract more qualified candidates who were no less pro-social (Ashraf, Bandiera and Lee, 2014). In fact, health workers attracted by the career incentives were more effective at delivering health services to communities. However, higher salaries may be less appropriate and/ or effective in drawing in better candidates in contexts where public sector workers already earn well above comparable market wages.

As discussed earlier, problems of poor performance and poor service quality in the public sector cannot simply be attributed to government workers being underpaid. In fact, high pay may be part of the problem – particularly if it is not linked to performance and when combined with contractual rigidities that effectively prevent hiring. For example, the recent nationwide doubling of all teachers’ salaries in Indonesia failed to improve education outcomes because teachers did not risk losing their jobs if they underperformed (de Ree et al., 2012). Public sector jobs are typically secure, well paid, undemanding, and highly sought after. Unless hiring is merit-based and resistant to corruption, these jobs will be offered to well-connected, low-ability individuals rather than high-ability, non-connected individuals.

In practice, public sector positions are often not widely advertised in developing countries and positions are often filled by individuals with informal connections. More open, transparent recruitment processes could go a long way toward ensuring the best candidates are considered fairly for jobs. The application process needs to be democratised so that people from anywhere in the country have a chance to work for the government and serve their communities.

Policy recommendations

For decades, developing country governments have been introducing numerous strategies to improve public sector performance with mixed results.

Research is finally beginning to catch up by rigorously testing some of the latest public sector reforms to gain a more solid understanding of what approaches work in different contexts.

There is now some clear evidence that performance-based incentives, both monetary and non-monetary, can positively impact public sector performance – and the key lies in designing and implementing them well. Incentives should be tied to clear, measurable targets that meaningfully capture the desired outcomes, with care to avoid unintended consequences like shifting effort away from other important tasks not linked to incentives. Exploring politically feasible strategies to introduce merit-based reforms that may require some punishing or firing of under performers – rather than only focusing on the reward side – is an important related challenge.

It is also critically important to hire the right people from the start. In fact, focusing on new recruits may be a more effective strategy than trying to reverse the under performance of existing workers. Offering attractive performance-based incentives may help to draw in the right candidates, feeding a virtuous circle.

Finally, the long-term challenge for public sector organisations is not simply to attract more competent and motivated staff but also to begin changing institutional environments. Building institutional cultures that discourage corruption and promote sustained professionalism should help to ensure that good staff can be retained and continue to be motivated to perform well over time.

To conclude, some key points for policymakers include:

- Financial incentives linked to performance can help to attract better qualified staff and motivate better outcomes in the public sector.

- Performance incentives should be salient, simple, and based on desired targets that are clear and measurable.

- Be careful to avoid the risks – incentives can sometimes reward undesired behaviour or shift attention away from other important tasks not linked to incentives.

- Consider using non-financial incentives such as social rewards and performance-based postings and promotions, which can be both cheaper and more effective than cash incentives.

- Pilot-test, evaluate, and as needed adjust incentive schemes continually to ensure they achieve the intended goals.

- Effective, transparent advertising and selection processes are important for attracting qualified and motivated candidates to government jobs.

FURTHER QUESTIONS FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY

- How can incentive designs provide the right level of flexibility? How can workers be given more autonomy and discretion in ways that motivate good performance rather than inviting corruption and worse outcomes?

- What strategies can minimise the risk of financial incentives having unintended perverse consequences?

- What are innovative and cost-effective ways to motivate better performance using non-financial incentives such as leveraging social pressures

and recognition? - How can governments use improved, more open strategies for advertising and filling job openings in order to attract more qualified candidates?

- How can governments foster institutional cultures of diligence, pride and professionalism to promote productivity?

- How can data and technology be leveraged to support better public sector performance?

References

Baicker, K. and Jacobson, M. (2007). ‘Finders keepers: Forfeiture laws, policing incentives, and local budgets’. Journal of Public Economics.

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E. and Glennerster, R. (2008). ‘Incentives for Nurses in the Indian Public Health Care System’. Journal of the European Economic Association.

Basinga, P., Mayaka, S. and Condo, J. (2011). Performance-based financing: the need for more research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 89.

Boyne, G. A., James, O., John, P. and Petrovsky, N. (2009). ‘Democracy and government performance: Holding incumbents accountable in English local governments’. Journal of Politics.

Dal Bó, E. and Finan, F. (2016). At the Intersection: A Review of Institutions in Economic Development. Economic Development Institutions Working Paper Series.

De Ree, J., Muralidharan, K., Pradhan, M. and Rogers, F.H. (2015). Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on the Impact of an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increase on Student Performance in Indonesia. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Dixit, A. (2002). ‘Incentives and Organisations in the Public Sector’. Journal of Human Resources XXXVII.

Duflo, E., Hanna, R. and Ryan, S. (2012). ‘Incentives Work: Getting Teachers to Come to School’. American Economic Review, 102(4): Gertler and Vermeersch.

Finan, F., Olken, B. and Pande, R. (2015). The Personnel Economics of the State. NBER Working Paper No. 21825. Glewwe, P., Ilias, N. and Kremer, M. (2010). ‘Teacher Incentives Based on Students’ Test Scores in Kenya’. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2.

Khan, A. Q., Khwaja, A. I. and Olken, B. (2016). ‘Tax Farming Redux: Experimental Evidence on Performance Pay for Tax Collectors’. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Khan, A. Q., Khwaja, A. I. and Olken, B. (2016). Making Moves Matter: Experimental Evidence on Incentivizing Bureaucrats through Performance- Based Transfers. International Growth Centre: Working Paper.

Muralidharan, K. and Sundararaman, V. (2011). ‘Teacher Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from India’. Journal of Political Economy.

University of Chicago Press.

Nava, A., Bandiera, O. and Kelsey, J. B. (2014). ‘No Margin, No Mission? A Field Experiment on Incentives for Public Service Delivery’. Journal of

Public Economics.

Nava, A., Bandiera, O. and Lee, S. (2015). Do- Gooders and Go-Getters: Career Incentives, Selection, and Performance in Public Service Delivery.

Working Paper.

Olken, B., Onishi, J. and Wong, S. (2014). ‘Should Aid Reward Performance? Evidence from a Field Experiment on Health and Education in Indonesia’. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Olken, B. and Pande, R. (2011). Governance Review Paper. J-PAL Governance Initiative.

Perry, J. L. and Hondeghem, A. (2008). ‘Building Theory and Empirical Evidence about Public Service Motivation’. International Public

Management Journal.

Rasul, I. and Roggery, D. (2013). Management of Bureaucrats and Public Service Delivery: Evidence from the Nigerian Civil Service. International Growth Centre: Working Paper.

Citation

Bandiera, O., Khan, A. and Tobias, J. (2017). Rewarding bureaucrats: Can incentives improve public sector performance? IGC Growth Brief Series 008. London: International Growth Centre.