Barriers faced by women in labour market participation: Evidence from Pakistan

Data from a job-matching service in Pakistan reveals differences in how men and women search for jobs, and lends insight into the barriers women face in labour market participation.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our International Women’s Day campaign and is based on this IGC project.

At 22%, Pakistan has one of the lowest female labour force participation rates in South Asia. The emerging reasons behind this low rate are a lack of access to safe transport, social norms, and household responsibilities that prevent women from having the time to work. However, one area which has received less attention is the job search process itself. We discuss the differences in job search methods across women and men, and what this reveals about the barriers that women in the labour market face.

Our team at Duke University and the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) created “Job Talash”, a job-matching platform. Our team first conducted a representative survey of over 50,000 households in Pakistan’s Lahore that included a question on whether members were interested in signing up for a job-matching service. Over 10,000 individuals signed up for Job Talash.

By asking questions about job search methods at the sign-up stage, our survey limits the sample to people with a revealed preference for participating in the labour market, thus making our data especially relevant to the employment-seeking process. In addition to collecting data on the job-seeker side, CERP conducted a survey of over 1,200 firms (enrolled on our platform) in Lahore that provided information on recruitment methods and candidate preferences.

Like in any country, job-seekers in Pakistan search for jobs through different methods including searching through networks, sending applications, answering ads, and visiting worksites. The most popular job search method in this sample was searching through networks, with 27% of the sample using this method. Additionally, 16% of the sample applied to prospective employers, and 11% checked worksites (this included people who search for work on a daily basis, such as carpenters, masons, and household helps, as well as people who visit businesses that may be hiring, such as office workers.)

How job search processes differ by gender

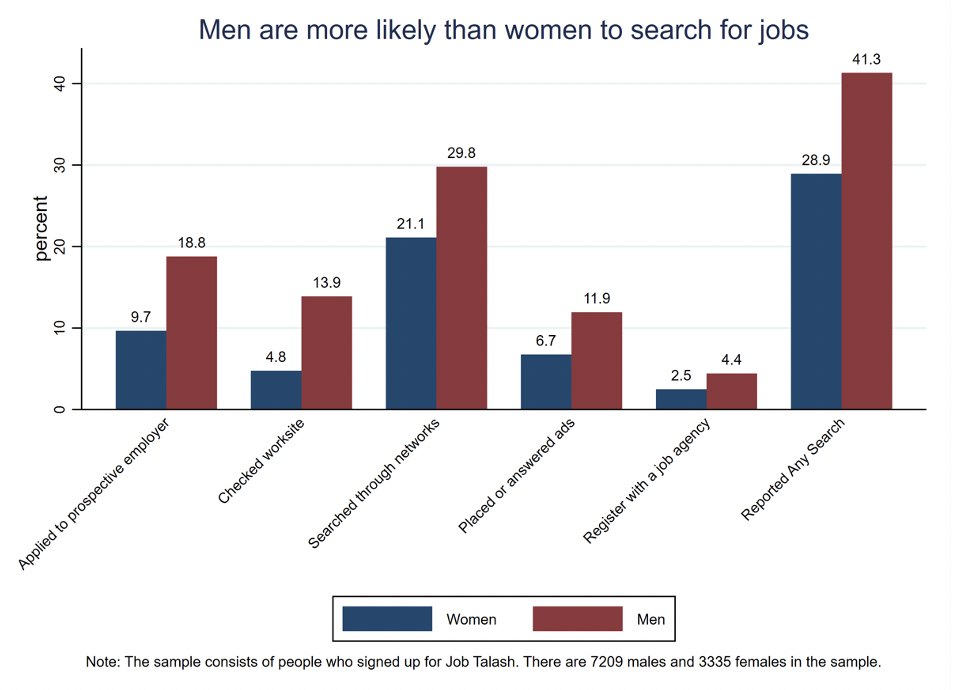

Women and men in Pakistan who are interested in working search for jobs at different rates and using different methods. For instance, men are more likely than women to search for jobs; indeed, 41% of men looked for jobs using any search method, compared to only 29% of women. Further, men were also more likely to look for jobs within each job search method.

Figure 1: Among people looking for work, men are more likely than women to have searched actively for jobs

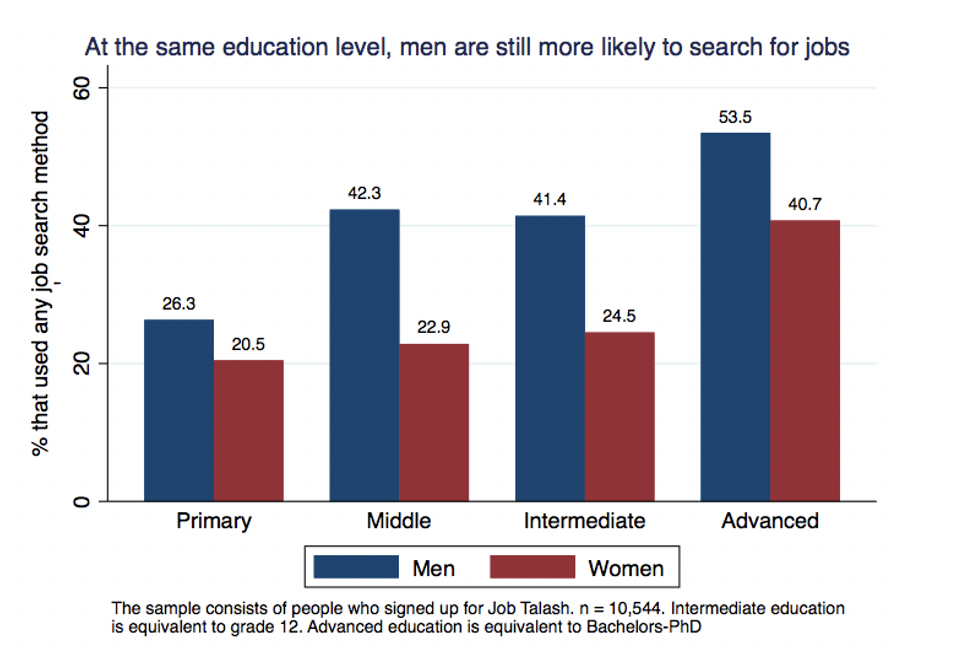

Even within men and women at the same education level (for example, people with advanced education), we find persistent differences with 54% men actively searching for jobs compared to just 41% of the women. For women and men with more than three years of work experience, 44% of men actively search for jobs, while this figure is only 35% for women.

Figure 2

From the time and effort that respondents put in to enrol in the Job Talash service, we infer that women who applied for the service are just as interested and motivated to find a job as men. This is because the enrolment process requires respondents to participate in a long and detailed survey that an individual not interested in finding a job would be unlikely to undertake. Yet, as the data above demonstrates, men are consistently more active in their search efforts than women in the sample, regardless of education and experience. This could indicate that women may be facing certain barriers to their job search efforts relative to men.

For instance, in their job search process, women may have less time to search for jobs due to household responsibilities, difficulty finding safe transportation to interviews, and a lack of access to networks that provide referrals and information about jobs. Through a household survey, we collected data on job searching through networks that allowed us to investigate the potential job search barrier of a lack of access to networks.

Networks play a vital role in recruitment

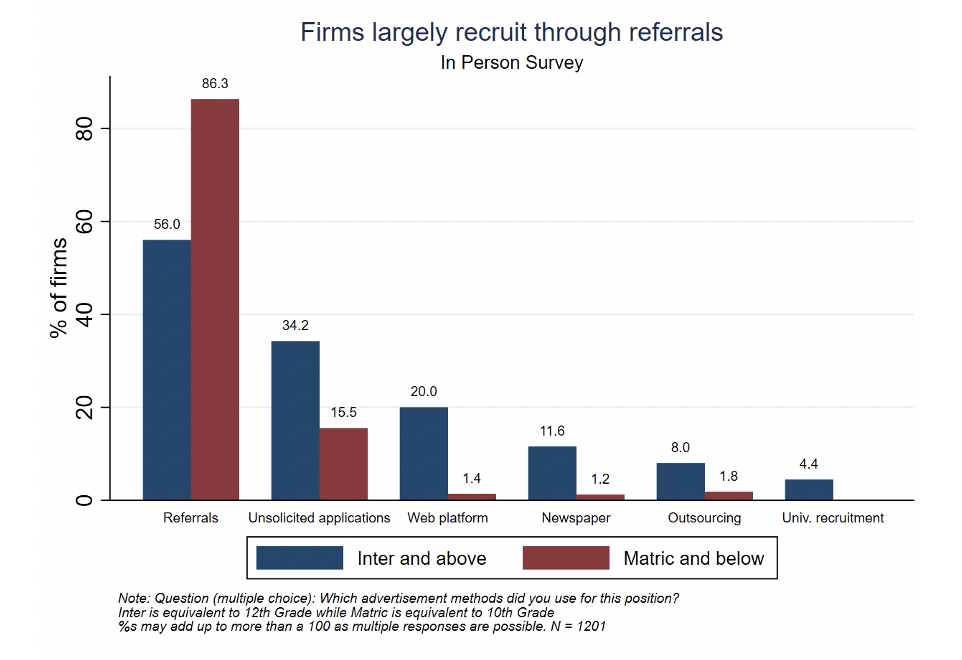

We find that job search through networks is the predominant job search method (see Figure 1). Through a representative survey of 1,200 firms across Lahore, we also found that referrals from networks were the most common hiring method. Indeed, 86% of firms hiring for people who have completed 12th grade (final year of schooling), and 56% of firms open to hiring people who are less educated used referrals to recruit candidates.

While firms largely recruit through referrals for both male and female roles, women are less likely to search through their networks to find jobs. As shown in Figure 2, 21% of the women in our sample search through networks, while this number for men is 30%. This difference could imply a significant barrier to job searching for women: since they use networks less than men, they may not be learning about job vacancies available to them.

Figure 3

Do women lack access to networks?

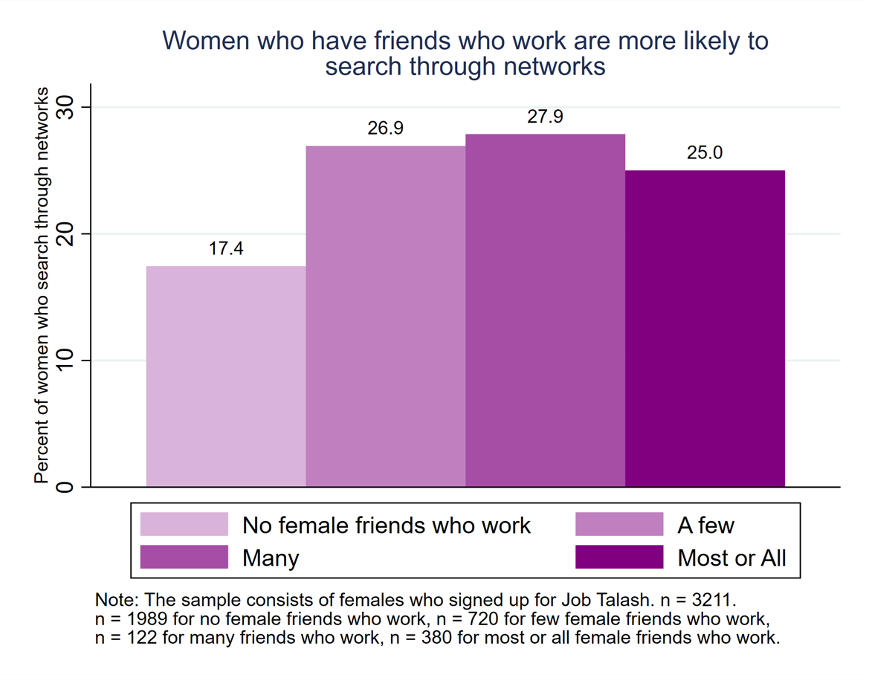

One potential reason for the pattern seen above could be that women search less through networks because they simply do not know many other working women. In the Job Talash sample, 62% of women reported having no working female friends, and 47% did not have any working female relatives.

Moreover, among women who expressed an interest in searching for jobs via Job Talash, we find women who have working female friends are more likely to search through networks, compared to women who did not have any. Further, women who reported having a few or more working female friends are 10 percentage points more likely to search through networks than women who did not have any. There is no significant difference in the percentage of women who search through networks between women who have a few, many, or almost all working female friends. This could suggest that a woman with any number of working female friends will ask those friends about job openings. However, women with more working female friends are more likely to be successful in their network searches since they have more connections.

Figure 4

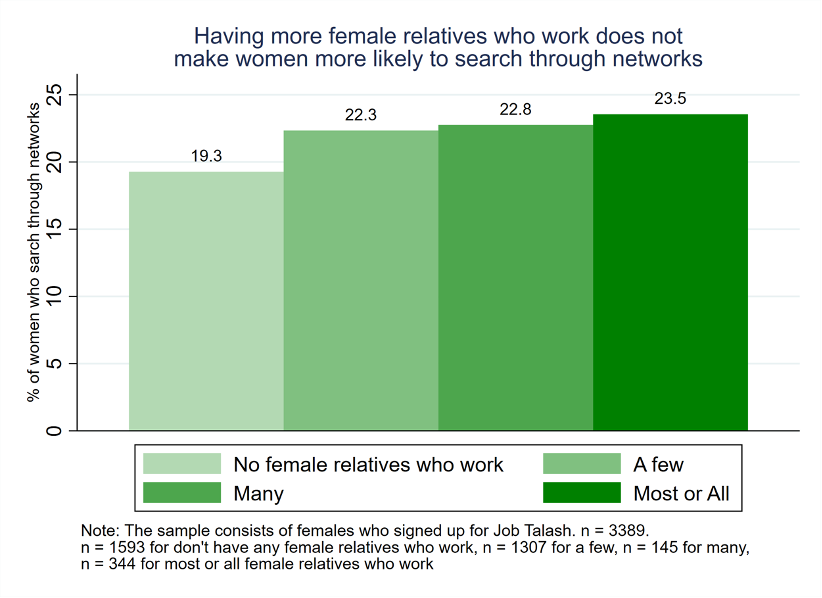

However, there is no significant difference between women with working female relatives and women without them. One potential reason for this could be that women are more likely to search for jobs through their friends than their relatives, potentially because their friends are likely of similar age and education and thus, have more relevant information about job vacancies.

Figure 5

Next steps for research

These findings indicating that women in urban Pakistan are interested in working but face barriers in their job search demonstrate a potential area for policy to address. Policies that reduce the barriers women face in job search would serve to economically empower the many women that are interested in working but have not found work. This could increase economic activity and enhance GDP potential for the country by expanding the workforce.

Our research suggests that one barrier women face in the job search is that they lack access to networks that can provide information about job vacancies. Potential policy solutions to address this barrier could include the organisation of women collectives for networking and the creation of opportunities for firms to share job postings outside of their networks. Analysis is under way on how women and men respond to job postings they are sent by text message through Job Talash. Since Job Talash provides job vacancy information without the need for networks or transportation, we can analyse if a job posting platform can help eliminate barriers women face in job search.

In addition to the job search barrier of women having limited access to networks, CERP and researchers at Duke University are also investigating the potential barrier of women not being able to find or afford safe transportation. We are conducting an RCT to investigate how door-to-door pick-up and drop-off service to places of employment affects job search behaviours for women and men.