Blurred lines: East African Community integrates in fits and starts

Efforts to integrate regional trade in East Africa gathered some, albeit weak, momentum this summer, with the implementation of the EAC Common Market (CM) protocol, which aims to harmonise commercial regulations between Partner States. This post documents the events driving and preventing the progress of integration.

This summer’s news paints a conflicted picture of integration in the East African Community. The EAC Common Market protocol went into effect July 1, with more ongoing clashes than fanfare. Observers and policymakers alike remarked on the persistence of non-tariff barriers, while local producers and their representatives worry over how trade disruptions will affect incomes and local revenue.

Reviving momentum through infrastructure…

Yet signs of progress remained highly visible: local press reported plans to launch One-Stop-Border-Posts between Kenya and Tanzania (Holili-Taveta), Kenya and Uganda (Busia-Malaba), and Burundi and Rwanda (Kanyaru-Akanyaru). In July, observers saw over $200 million dedicated to massive highway improvements linking Mombasa port to Tanzania. July saw proposals for a joint railway project being pitched by Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania; the proposal aims to raise over $7 billion for lines interlinking the three markets. The public also received some encouraging soundbites in August from the EAC’s respective governments on energy projects and infrastructure for oil exports.

Energetically optimistic reports with catchphrases like, “fast-tracking development” and “unlocking East Africa’s potential,” echo a widely broadcasted, and by no means unwarranted, hope that improving internal transport infrastructure will facilitate the exploitation of gains from additional trade. This includes the recently renewed and extended Africa Growth and Opportunity Act. American President Obama’s visit to the region also reinforced the accepted belief that “It shouldn’t be harder for African countries to trade with each other than it is […] to trade with Europe and America.”

But the spirit is not moving us

Less encouraging has been the trade disputes over sugar and rice, as the region’s less efficient members adjust to competition with a common market. For example, Tanzania had initially been granted a zero percent duty for rice imports due to its high domestic prices. June saw it first threatened then punished with the imposition of the EAC 75% duty on its rice exports to Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya, following charges that its traders were blending local rice with Asian imports. Tanzanian officials called on its traders to follow EAC guidelines, reasoning that foreign rice in Tanzanian markets was falsely imported under the pretence of transhipment to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

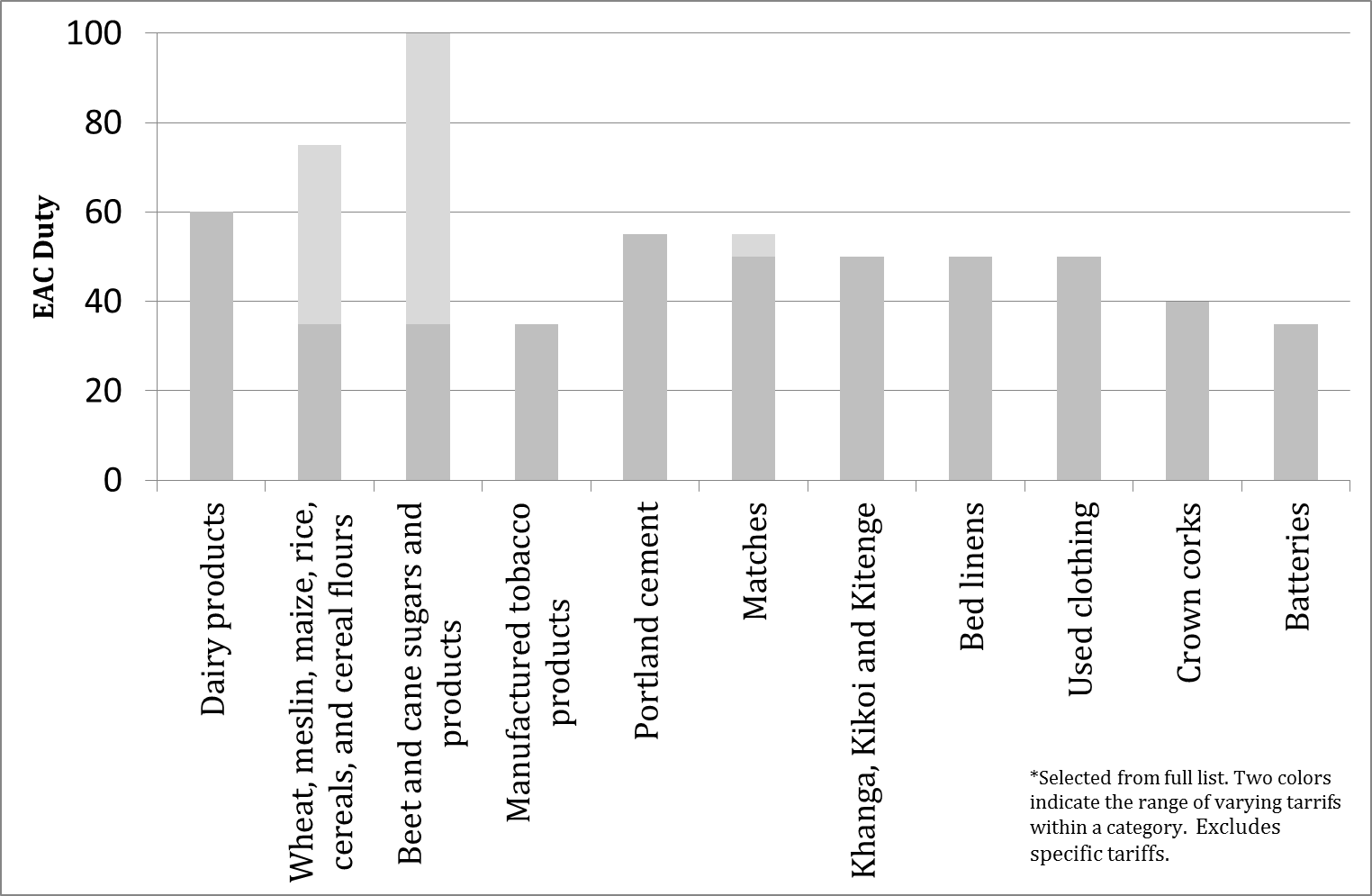

EAC sugar trade had a more amicable start in July, with Tanzania and Rwanda being granted permission to import sugar “from partner states that have excess production,” using the CM protocol’s “stay of application” provision which allows member states to temporarily deviate from the common external tariff’s Sensitive Item duty (see Figure 1). Under the stay of application, Tanzania and Rwanda can apply duties below 100% (50% for three months and 25% for twelve months, respectively) to imported sugar. In a perfect world, these limits, combined with adequate enforcement of rules of origin (RoO), should prevent traders from exporting local sugar mixed with imports.

Figure 1: EAC Sensitive Item List

However, deals affecting levels of protection have historically been associated with subsequent accusations of export dumping into partner markets, as was the case in the EAC’s other big summer news event. August saw a controversial bilateral deal between Presidents Museveni and Kenyatta to reopen the Kenyan market to Ugandan sugar and the Ugandan market to Kenyan beef.

The deal resolved Uganda’s nearly twenty year import ban of Kenyan beef due to unsettled concerns about mad cow disease. Kenya, meanwhile, had been blocking Ugandan sugar imports since 2012, when it accused Ugandan traders of exporting cheap imports to Kenya and thus required them to carry permits. (Of special note is that these imports were duty free, under a prior deal brokered in order to help Uganda fill a domestic shortage.) The permit requirement prompted Uganda’s retaliatory accusation of a Kenyan non-tariff barrier. While the dispute’s resolution is a step forward, the political backlash in Kenya demonstrates how difficult removing protection can be.

Slow and complex, not short and sweet

While the summer’s celebrated infrastructure investments signal commitments to integration, the rice and sugar controversies highlight the challenge policy-makers face in simultaneously adhering to EAC regulatory obligations while improving the competitiveness of domestic production. Of obvious priority is the need to better monitor and enforce EAC rules of origin. This is reflected in a comment by the secretary general of United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD): “If there was an efficient and properly working customs union authority there would be no notion of exporting from Uganda to Kenya because you would not call that exporting.”

Consistently identifying domestic production can help address a second issue blunting the spirit of regional free trade: EAC states’ repeated reliance on extra-EAC suppliers to meet domestic production gaps. The real test of progress for the region is whether its leadership can foster a regionally-focused mind-set and promote norms that consistently forward EAC priorities, notwithstanding the ultimate beneficiaries’ national origin. This challenge is currently exemplified by Pakistan’s request to Kenya to lower its import duty on rice.

Finally, while inconsistent customs practices disrupt market integration, broad similarities in the region’s principal products—like rice and sugar—create competitive frictions that run against harmonisation efforts. Regional integration is thus a politically complicated process to implement, given persistent incentives to protect local groups. Ideally, the EAC will gain competitiveness as a block and benefit from improved economies of scale and access to regional and international markets. However, should they fail to harmonise processes and uniformly apply rules, the EAC members risk a zero sum situation and further delays.