Consumer welfare impacts of high transport costs in rural Ethiopia

Access to a variety of manufactured goods reduces in relation to the distance from urban centers. Accordingly, reductions in transport costs increase consumer welfare through higher incomes, lower prices, and increased variety.

Transport and consumption in Ethiopia

Transport costs reduce consumer welfare, not only through lower incomes and higher prices, but also through reduced variety: choice fades with distance. We use data from a purpose-designed survey of shops and consumers in rural villages in Ethiopia and find that remoteness sharply reduces the variety of consumer goods available and estimate the costs to consumers of fading choice.

Geography

Ethiopia is an economy where issues related to high transport costs are particularly salient. The country is landlocked, meaning internal trade costs are strongly affected physical geography. It has a mean elevation of over 1000 metres, with the bulk of the population living on the high plateau, a terrain wrinkled with steep hills and mountains. As a result, Ethiopia has one of the lowest road densities in the world, despite substantial investment in new roads over the last decade.

Access to manufactured goods

For an average village, a fall of an hour in travel time is associated with an increase of about nine items or 18 brands. The average markup in prices between source and destination is between 10% - 15%.

Low urbanisation rates (at 17% compared to the sub-Saharan average of 33%) mean that for a large portion of the population, markets are remote and inaccessible. This particularly affects access to manufactured goods. Rural households produce much of their own food, and many services can be produced locally in rural areas.

Manufactured goods are typically either imported from abroad or produced in a small number of locations around the country. Consequently, domestic transport costs play a significant role in the availability of manufactured goods among Ethiopia’s rural communities.

Product variety

Remoteness affects product variety along several margins:

- In remote areas, previous research has shown that productivity is low and poverty is higher. If the demand for variety has a positive income elasticity, then remoteness will be associated with a reduction in variety.

- High transport costs will imply that individual varieties will be more costly in rural areas. If the cost of these (manufactured) goods is fixed, there will likely be a corresponding reduction in variety.

- The pricing power of retailers in remote areas – where market size may be too small to support much competition – may imply that shopkeepers prefer to restrict the set of varieties in order to focus on products with high margins.

The study

To examine the relationship between remoteness and market variety, we conducted a survey of 296 villages in 100 districts across the four main regions of Ethiopia. Villages were chosen so that the local market town was the only supplier of consumer goods, to serve as a benchmark for local availability.

We focus on manufactured consumer goods: this covers about 20 item groups from processed foods, drinks, garments, footwear, cosmetics to kitchen ware, hardware and small electronics. Within these groups there are specific items such as spaghetti, beers, soaps, plastic tableware, linens, notebooks, and batteries, and we can further disaggregate these by brands.

Methodology

Data were collected in shops in the market towns closest to the villages, and in shops and periodic markets (served by traders) in villages. Village officials and six households in each village were surveyed. These data allow us to examine how transport costs, incomes, the income distribution, and size of the local market affect the fraction of items available in a remote village compared to its nearest market town.

As road infrastructure is not randomly built across districts and villages; we needed to account for this non-random placement effect. By sampling up to three villages in the same district, and focusing on within district variation, we can account for placement at the level of the district. We find no evidence of placement effects within districts.

Findings:

Travel time and variety

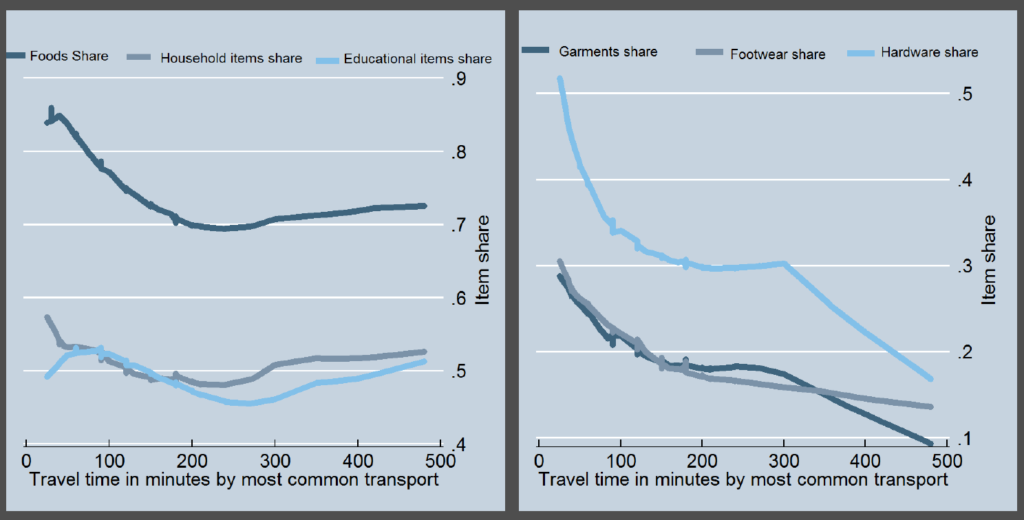

The first graph shows how the number of items drops off as transport times to town increase. There are sharp falls in the availability of processed foods and drink within 90 minutes of travel from town. Garments, footwear, hardware and electronics are even more limited in variety the further the travel time from town.

Figure 1: Share of items available against travel time to the nearest town.

Fixed transport costs

Part of the reason for the diminishing variety in remote villages are the fixed costs involved in taking goods further down the road. These costs include licences (for items), payment to village authorities, and the costs of transport and accommodation for itinerant traders, as well as inventory and storage costs:

- 38% of traders quote licences required (often by item type) as the reason for not trading other items.

- 33% quote lack of capital.

- 20% claim that the lack of demand in remoter areas dissuades them from carrying more items.

Availability

We establish that travel times to town, the level and distribution of income, and the size of the local market all serve to affect product availability in villages:

- Product vailability in a village increases by about four items for every half hour closer to town.

- An increase in market size of 10% raises availability by about 12 items.

- The average number of items in a village two hours from town is 43, relative to the 95 items available in town.

Thought experiment: The welfare impacts of low variety for consumers in remote areas

To assess the welfare impacts on consumers living in remote areas, we construct a theoretical framework of monopolistic competition among traders in manufactured goods. We use data on prices paid in town for identical (branded) items, and the prices they are sold for in the village, using two separate surveys to validate the date. We therefore estimate an average mark-up of 10-15% in remote areas.

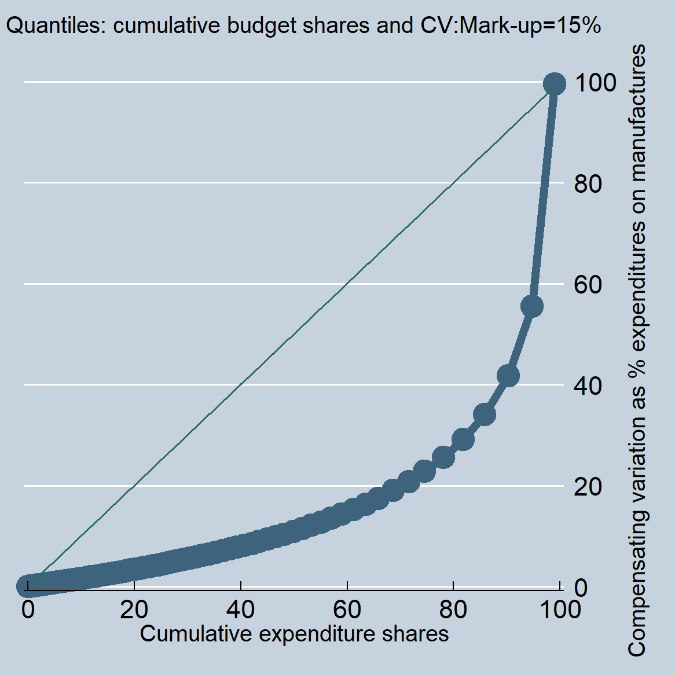

This finding allows us to estimate the welfare costs of low variety in manufactured consumer goods in terms of the compensating variation: if availability falls, what is the equivalent loss measured as a percentage of spending on manufactured consumer goods?

To determine this, we use information on the budget shares of spending by the median urban consumer.

This thought experiment considers the loss of not being able to consume the last or maginal varieties out of the full set in the consumer’s current basket – calibrating this loss based on both the estimated taste for variety and the budget shares. The total share of spending on manufactured goods for the median urban consumer is 18%.

Findings:

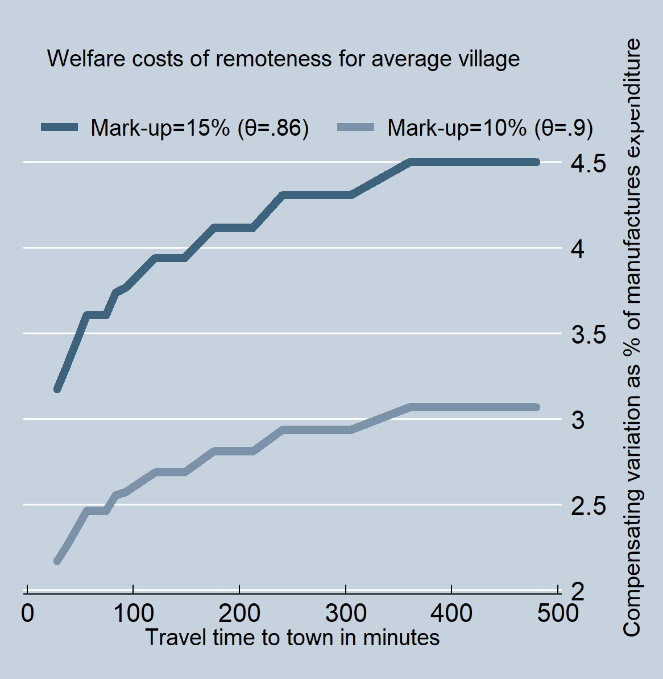

- The average welfare cost of loss in variety is estimated at an average of 5 - 7% of consumer expenditures on manufactured goods.

- Alternatively, the loss is 1 - 1.25% of total expenditure per capita.

- The top 20% of items take up more than half of spending on all manufactured items, which implies that the compensating variation from the loss of marginal items is small.

- The top 20% of items include processed foods (cooking oil, beer and flour) but also medicines and detergents.

We illustrate these findings below in two ways:

- Figure 2 shows a graph of how the compensating variation falls with cumulative budget shares (for the estimated mark-up of 15%).

- Using the data on remote rural villages, the particular way in which compensating variation increases across space for the “average” village for two different estimates of the mark-up.

Figure 2: Compensating variation: The costs of losing variety

Implications

The research shows how variety in manufactured goods reduces in relation to the distance from urban centers. Accordingly, reductions in transport costs increase consumer welfare through higher incomes, lower prices, and increased variety:

- There are significant welfare losses due to low variety in manufactured goods.

- Intra-trade costs (both mark-ups and transport costs) matter in affecting the margin of welfare losses.

- The average costs to consumers is about 5 - 7% of consumer expenditure on manufactured goods.

- Although the cost to consumers is not small, it reflects the fact that Ethiopian consumers are poor, meaning their share of spending on manufactured goods is low.

- Consumer costs will increase with rising incomes unless the corresponding domestic trade costs fall.

These findings also have implications for welfare measurement: poverty is underestimated since people in remote places have little to choose from. Equally, when access to manufactured goods increases, for example through infrastructure investment, estimates of the decline in poverty will be underestimated too.