COVID-19 funding in federal systems: Lessons from Nepal

With COVID-19, the federal governments of many developing countries are grappling with a crisis that requires both a central and local response. Coordinating across spheres can be tough, especially when the effects of the disease are amplified by other emergencies. Our survey of local governments in Nepal shows how mismatches between COVID-19 caseloads and funding can arise, and suggests an approach to close such gaps.

In many developing countries, the COVID-19 crisis has increased vulnerability to other shocks. Bangladesh is reeling from the pandemic with over 2,000 new cases announced in a 24-hour window at the beginning of August. This coincided with devastating floods hitting half of the country’s districts, killing 135 and injuring 21,000. Bihar in India is similarly battling the twin emergencies of COVID-19 and floods. International and domestic return migration gives an additional shock to overstrained health systems. For instance, in Ethiopia thousands of migrant workers are returning home, over 900 of whom have tested positive for COVID-19, placing extra strain on the medical system.

Federalism creates an additional vulnerability

The political economy of federalism means that developing countries with significant administrative decentralisation, such as Nepal, Sierra Leone, India, Rwanda, and Uganda, face an additional vulnerability. Many aspects of an effective response to the virus, such as testing, contact-tracing, and running quarantine facilities must be implemented at the local level. However, local governments often rely on federal funds to carry them out. This means coordinating across different spheres of government at a time when public health funding is both more vital and in shorter supply than at any time in living memory.

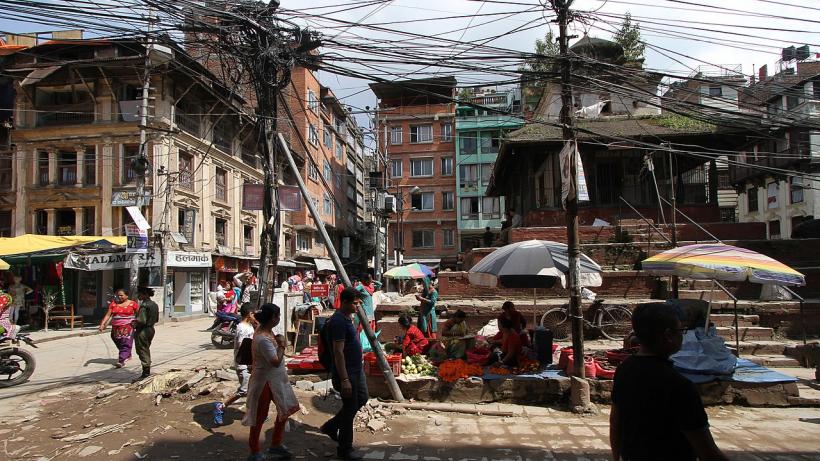

Nepal is the world’s youngest federal democracy, and its new institutions are up against a formidable test: the COVID-19 pandemic and severe floods, along with the imminent lean season. The federal, provincial, and local spheres of government need to coordinate to rise to these challenges.

Nepal’s federal structure

Nepal’s federal structure delegates many administrative decisions to the local level. Public health is a shared responsibility across governmental spheres, but primary healthcare and sanitation are exclusively local government functions. These local governments have an experience of less than three years to implement these newly assigned constitutional responsibilities. Municipal and ward officials are in charge of getting food to the needy, managing quarantine centres, and implementing testing and tracking schemes. These responsibilities will only grow more important in the coming weeks and months, as COVID-19 numbers rise at an alarming rate and the floods and landslides continue.

Our team of researchers conducted a survey of provincial-level officials across seven provinces and elected chiefs and deputies across 115 local governments, to assess the dynamics of the COVID-19 response. The data, collected in June prior to the end of Nepal’s full lockdown, reveal four key issues and inequities with local funding:

- Local governments roundly report a lack of adequate funds. They largely rely on their own budgets for COVID-19 related health activities, which are not sufficient. As such, local governments have a poor revenue base and they largely depend on federal transfer. There is also asymmetry in the capacity of local governments in terms of human resources, institutional arrangements, and political networking.

- There is substantial dispersion in the amount of local funding available. Officials report an average funding availability of $69,500 per locality (8.3 million Nepali Rupees), which ranges across local governments between 50¢ and $4.22 per person. To put this in perspective, at the low end that funding is enough to provide four surgical masks per resident, whilst at the high end it would enable rapid diagnostic tests for 52% of the population.

- The local governments facing the most serious outbreaks reported the least amount of funding to respond. This mismatch arises, in part, because high COVID-19 caseload areas are in the lowlands near the border of India, the Terai, where local governments had already exhausted much of their annual disaster funds on flood relief.

- Inter-sphere coordination remains messy. Provincial and federal authorities target funds to high COVID-19 areas by bypassing local governments and directly allocating funds to hospitals and district bodies. Local governments, however, continue to remain responsible for multiple federal government orders.

While the nationwide lockdown has ended and Nepali local governments have begun a new fiscal year, these problems may persist. Flooding has been severe in this season. And, as of 9 August, 100 local governments, around one-seventh of the total, had yet to present their budgets for fiscal year 2020-2021, according to data released by the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration. Concerningly, the highest number of unsubmitted budgets were from the hard-hit Terai region.

A need-based model

Our research leads us to suggest that a need-based model for health financing can help, and this is a model that could be developed for other federal systems. Present and anticipated COVID-19 caseloads can regularly inform additional budget allocations to local governments. Local governments with higher caseloads require access to additional funds for broader public health activities such as contact tracing programmes. These budget allocations can also be updated based on other local emergencies. Alongside, ensuring that provincial and federal governments develop transparent and justifiable criteria for allocating their funds across different bodies can help with coordination across spheres.

Rwanda provides an instructive example. The government is leveraging grassroots networks and local governments which have targeted more vulnerable households and areas. Already, the Rwandan government has been praised for its ability to mobilise funding in a focused and localised way.

Concluding remarks

As COVID-19 enters into the community transmission stage following the surge in infection and death rates, Nepal is facing strained challenge in managing health facilities like testing, tracing, and treatment through isolation. The specific case of quarantine financing demonstrates that need-based financing is indeed feasible: allocation of federal funds for quarantine management aligns well with caseloads.

It is now critically important that Nepal focuses on testing, tracing, and treatment. There are already more patients needing treatment than hospitals can absorb in the parts of the country most severely impacted by the crisis. Money needs to be directed to where it is needed. To achieve this, health financing needs to be evidence-based, and not just one-size-fits-all.

Our full brief, along with open access to our survey instrument, is available on the Yale Economic Growth Center website.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.