Curse of anonymity or tyranny of distance? The impacts of job-search support in urban Ethiopia

Urban jobs are key drivers of economic growth in developing countries. Finding ways to connect and match young and skilled workers with better jobs remains a key policy challenge. In Ethiopia, experiments with training and transport subsidies show great promise.

Unemployment is high among young people in Africa, especially in urban areas. While many young people come to big cities to find jobs, urban lives can be vulnerable. Jobs available are often irregular, informal, and unpleasant.

The existing evidence on how to effectively support young unemployed people in cities is limited. Cash grants, public works programs and training programs to improve skills for either employment or self-employment, have been shown to work with only limited success.

Golden opportunities

Source: DFID - UK Department for International Development

In this IGC project we show that job search assistance programmes can help young unemployed people in Addis Ababa to access formal urban labour markets and find better employment.

Can labour market policies improve youth outcomes?

We set out to test whether labour market policies can improve youth outcomes in two ways:

Signalling: Helping job seekers’ signal their skills to employers. Job seekers were invited to a job-search workshop. This was comprised of one day of testing where applicants engage in cognitive and non-cognitive skills tests, developed through discussions with hiring firms in the city, as well as a local educational institution. On a second day, participants were trained on how to apply for jobs, using certificates that reported the results from the tests that they took.

Matching: Giving job seekers the means to pay the high costs of transport in order to get information about better jobs. Here, we gave young people money to cover the costs of a return trip to the centre of the city, on a daily basis for up to three days a week, for 4 months.

Through the use of a randomised controlled trial we are able to estimate the impact of these two programmes for a sample of nearly 4000 young job seekers in the city, who were without permanent work when we first met them in March 2014.

In Addis, the farther residents live from the centre, where most good jobs are found, the more detached they are from the formal labour market.

Both experimental treatments had a positive and significant impact on the quality of jobs held by participants one year later. Both treatments increased the probability of finding a formal job, with clearly written agreements, by about 5.5 percentage points (a 25% increase) and the signalling workshop increased the probability of having a permanent job with secure tenure by 6.7 percentage points (a 40% increase).

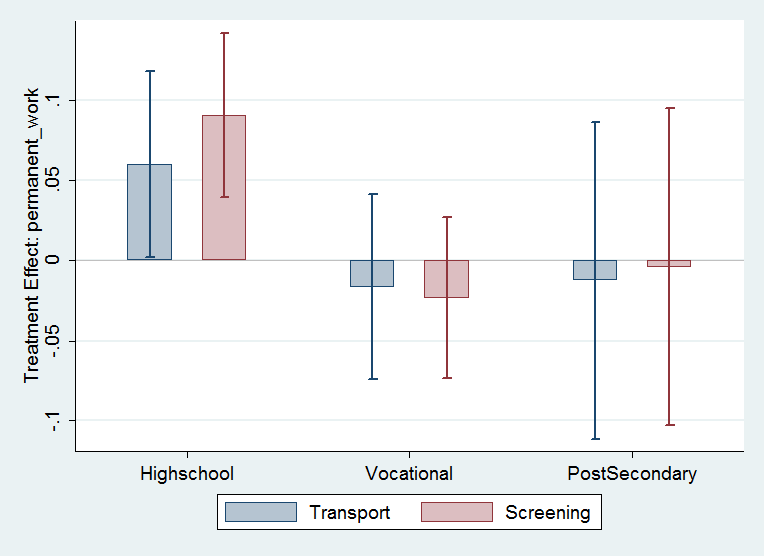

Figure 1: Impact of the transport and screening treatments on having a permanent job, showing heterogeneous effects for different educational attainment. Post-secondary includes all University degrees and diplomas, which Vocational education refers to TVET graduates. 95% confidence estimates on the treatment effects are shown.

We found that the results were strongest for those that were most detached from the labour market: women, and young people who had finished high school but not gone on to higher education benefited the most from both interventions.

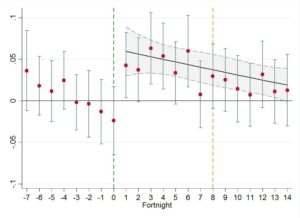

We use a phone call survey to follow individuals in our sample over time, to track the trajectory of their employment and search strategies. We find strong evidence that the transport treatment improved employment by allowing young people to spend longer searching for jobs. By contrast, the information and certificate program did not increase job search intensity, but rather improved the efficacy of job search: we find a significant impact on the conversation rate of job applications into interviews and job offers.

Figure 2: Impact of the transport treatment on job search, estimated for each fortnight. Fortnight 0 is the week at which the treatment began, fortnight 8 is when the transport subsidies ended. 95% confidence intervals are shown. The black line is a quadratic estimate of the treatment effect over time, starting from week 1, with a 95% confidence interval shown in grey.

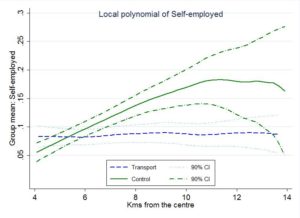

The job seekers in our study lived at least 2.5kms from the city centre. In Addis, the farther residents live from the centre, where most good jobs are found, the more detached they are from the formal labour market. Self-employment in the informal sector is much more common outside of the city centre. People who live farther from the centre are less likely to apply for jobs using formal means, with CVs and certificates.

Our transport treatment completely mitigates this effect of distance, causing a shift in job search methods and employment towards the formal sector for people living further away from the city.

Figure 3: Probability of being self-employed as a function of distance from the city centre, comparing the control group to the transport treatment.

Policy recommendations

This research shows the distance between where jobs seekers live and where they can access to jobs, as well as their ability to signal skills reduce young people’s chances to obtain good jobs.

Young people in Addis Ababa want good jobs. Not all of them will find one, but our research shows that some of them are missing out because of disadvantages that they face. Policymakers should concentrate on helping motivated young job seekers overcome constraints preventing them from getting access to jobs for which they would be a good match.