From transport to growth corridor: Do communities benefit from the Central Railway Transit Corridor in Tanzania?

The government of Tanzania has embarked on a journey to revive the railways, through its investment in the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) on the central corridor.

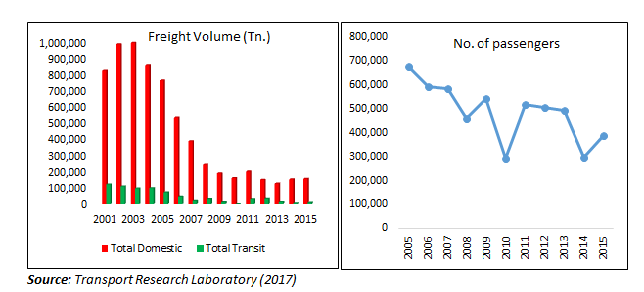

The 2,561 km Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) line will connect the port of Dar es Salaam to Tanzania's land-locked neighbours (Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and Eastern DR Congo). The project is estimated to cost $14.2 billion, and is due for completion in 2024. Construction of the first phase (from Dar es Salaam to Morogoro) is under way. Clearly, the importance of the Railway Corridor project is not only in facilitating transit and domestic freight and passengers, but also the economic stimulus it provides to the communities along the corridor. However, despite its importance, performance of the present central railway has deteriorated dramatically in recent decades, largely due to operational challenges arising from under-investment (see Figure 1). The share of central railway in domestic and transit freight decreased from 70% in 1980s to less than 10% in 2015.

Figure 1: Freight volume and passenger number by Central railway

This present study builds on a previous IGC funded project that surveyed enterprises and households along the central railway route. The current project examines the potential for a rehabilitated central railway in stimulating socio-economic transformation of communities in the transit corridor.

Findings

1. Poor and worsening railway operations have eroded any economic potential the railway might previously have brought to communities along the corridor.

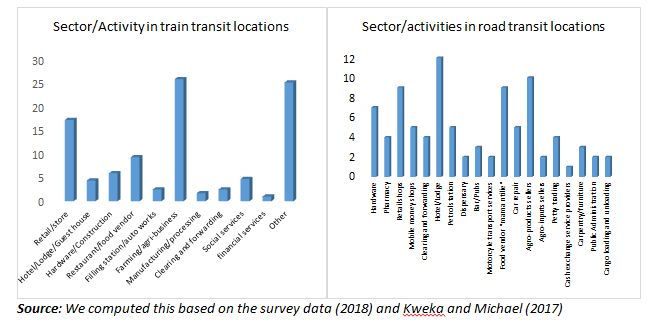

Following the deterioration of the railway transport sector over the past 10 past years, the growth prospects of the transit locations have faded away. Improved road infrastructure has led to the emergence of new and thriving townships (e.g. Igurusi, Chalinze, Gairo, Igunga, etc.), with a number of them becoming major secondary cities (e.g. Dodoma, Morogoro, Tabora, Isaka, etc.). By contrast, towns along the central railway that are far from the central road network have been deteriorating (e.g. Ruvu, Kaliua, Malampaka, etc.). Businesses in railway towns are small and less diversified compared to business activities along road (trucking) transit towns (Figure 2). With a lack of diversification, job opportunities (and hence income) are limited.

Figure 2: Type of economic activities in transit locations

2. With limited choice, road is currently the most used and preferred mode of transport, but the potential demand for railway transport is significantly high.

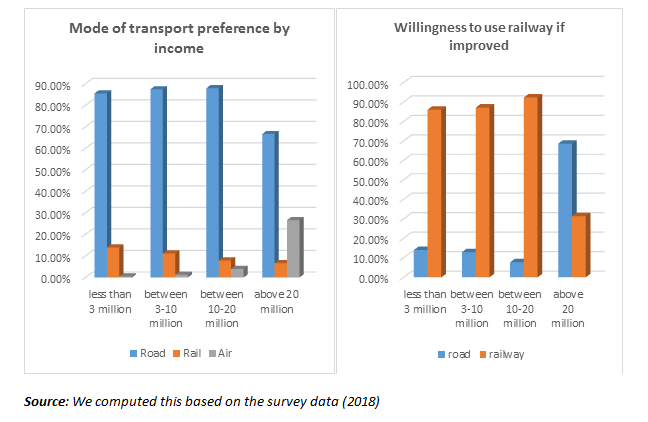

Findings reveal that road transport is currently the most used and preferred to railway. Travel time and costs are the major considerations in determining the choice of mode of transport between rail and road for both passenger and freight transport. Interestingly, the findings show that respondents with relatively higher levels of income use road transport more compared to the lower income category. However, despite the deterioration of railway operations, the potential demand for railway transport services appears to be significantly high. First, in some cases, railway is the only transport service available, including in remote areas where road transport is relatively too expensive (e.g. Kigoma) or underdeveloped (e.g. Mpanda). Second, there is huge potential for transporting agricultural produce and industrial output, showing the opportunity for railway transport to facilitate access to markets and bring about efficiency by reducing transport time and cost.

3. The impact of railway rehabilitation on domestic market integration will depend on the quality of complementary (especially road) infrastructure.

In principle, one of the advantages of the railway is to drive down transport costs, increase rural-urban linkages, and improve access to markets. However, our survey suggests that chronic inefficiency undermines this contribution. Traders use the road network which, though costlier than railway, is quicker and more reliable. For instance, although Ruvu, a ‘railway town’, is closer to Dar es Salaam, the price of sugar is 12% higher compared to Isaka, which is further away, but road connected. Even allowing for the fact that the railway is not fully and efficiently running, unreliable feeder roads connecting to the railway infrastructure, contribute further to the ineffective use of the railway by the surrounding communities and producers. This implies that the SGR would need to be complemented by better feeder road networks to enhance its envisaged impact to the communities along the corridor, particularly the productive areas.

Survey data show that that 68% of agricultural produce is transported and sold in distant regions or towns. Furthermore, the data show a total of 234 small industries in all the stations, most of which dealt with food processing, agro-processing, household items, textile and leather products, metal and metal products, and building materials. Third, the survey results show that almost all households are engaged in one form of travelling or another, with frequent trips (about three times a year per household) to/from Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Kahama, Mwanza, and Tabora. Finally, as shown in Figure 3, over 80% of traders and households are willing to use railway if it is available and improves efficiency. Most traders reported that they would be willing to pay slightly more for a faster and more reliable movement of cargo.

Figure 3: Preferred mode of transport by income level

4. Prospects for the SGR are positive but there is a risk of over-optimism, which presents both opportunities and challenges.

Ideally, when completed, the SGR will have the potential to significantly lower transport costs in Tanzania and the region, hence reducing prices of goods and increasing welfare. Indeed, most respondents reported high expectations on SGR as a vital lever for transforming their local economies and social lives, especially through increased market and business linkages. Nonetheless, these expectations also come with some speculations and anxieties. First, communities along the corridor are curious to know if their station will be picked for SGR, understandable given the fact that the new railway stations will potentially benefit from improved railway operations.

Another important question is what would be the implications for the existing and thriving truck or road transport industry. Many believe that the transport efficiency arising from full scale development of railway transport will lead to downsizing the number of trucks and buses along the central corridor, especially for long-distance trucking for some goods. As an indication of the expected efficiency in cargo movement, data from Tanzania Railway Corporation (TRC) show that one single SGR train is expected to handle 10,000 tonnes, which is equivalent to replacing 500 trucks in a single trip. Views expressed by respondents indicate that some business activities will drop, thus affecting livelihoods and jobs at least in the short-term. Although there is no empirical evidence so far, our qualitative surveys point to a more general implication that in the long-term, efficiency gains will outweigh the short-term losses.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Overall our findings indicate that, although the railway in its current state adds very little to the national or local economy, the benefits to rehabilitation of the SGR may be substantial in supporting economic transformation. Based on the above findings, we recommend the Government to:

(i) Focus on the need for complementary infrastructure linking train stations to the production areas to improve access to markets and bring about expected transformation. This includes roads and other railway lines linking potential ‘value’ sites (farms, production sites, industries, etc.) to the train stations.

(ii) Put more emphasis on strategies for supporting production activities along the corridor, which would potentially increase cargo volumes for the SGR in future. That is, in addition to current emphasis on physical infrastructure, efforts should be put on promoting investment in economic activities which have potential to generate future cargo volumes and stir local economic development.

(iii) Manage expectations around SGR by collaborating with Local Government Authorities (LGAs) to develop proactive strategies for amplifying the benefit of transport infrastructure to the communities along the corridor. This involves two levels of interventions. First, support LGAs in their formulation of strategies or plans to empower communities to take advantage of the SGR project during and after construction. Second, the Government should engage with industry operators on the opportunities for providing complementary services (e.g. linking destination/source) for the SGR.

(iv) Conduct a follow up study to assess potential opportunities for increased production and propose viable projects for realising those opportunities. Our current study provides a useful starting point for identifying investment opportunities that would generate increased traffic for the new railway capacity and support the transformation from transport to a growth corridor. Indeed, a follow-up study can help in identifying the complementary infrastructure to maximise benefits to the communities as well as generate data for assessing performance of the corridor overtime.

References

Kweka, J and S Michael (2017), “Assessing the economic benefits of transit trade: The case of Tanzania”, IGC Project, https://www.theigc.org/project/assessing-economic-benefits-transit-trade-case-tanzania/