Government decentralisation and reform in Myanmar’s roads sector

Myanmar is in the midst of an historic shift towards a more democratic and responsive government. In a radical departure from a highly centralised structure, the 2008 Constitution established 14 sub-national governments, with partially elected parliaments. In addition to their devolved political authority, a range of finance and administrative functions were ceded to this newly minted level of government. Local politicians at sub-national level must now win elections, conceptualise policies and manage their own budgets to be used as tools to respond to their citizens’ needs.

Decentralisation in Myanmar

In theory, such decentralisation of political power and fiscal responsibilities, away from the centre and closer to the people, is often perceived to be a good thing. After decades of dictatorial central rule, these reforms have been celebrated as an important early step toward a more democratic, responsive and accountable system of governance in Myanmar (Nixon et al., 2013). The citizens’ enthusiasm to engage and participate in the political process carries encouragement and hope.

In contexts with weak traditions of citizen participation, decentralisation can be an important first step in creating regular opportunities for citizen-state interaction. It can help create demand for downward accountability and for more participatory channels to voice local needs. However, decentralisation itself cannot spontaneously translate to improved governance and downward accountability (Bardhan and Mookherjee, 2005).

Decentralisation and accountability

There is a growing understanding that local political economy factors are also integral to the success of decentralisation reforms. This includes the incentives of the individual government officials involved in decision-making processes and the mechanisms through which they are held accountable. The accountability of decentralised governments is shaped considerably by the scope of local decision-making autonomy.

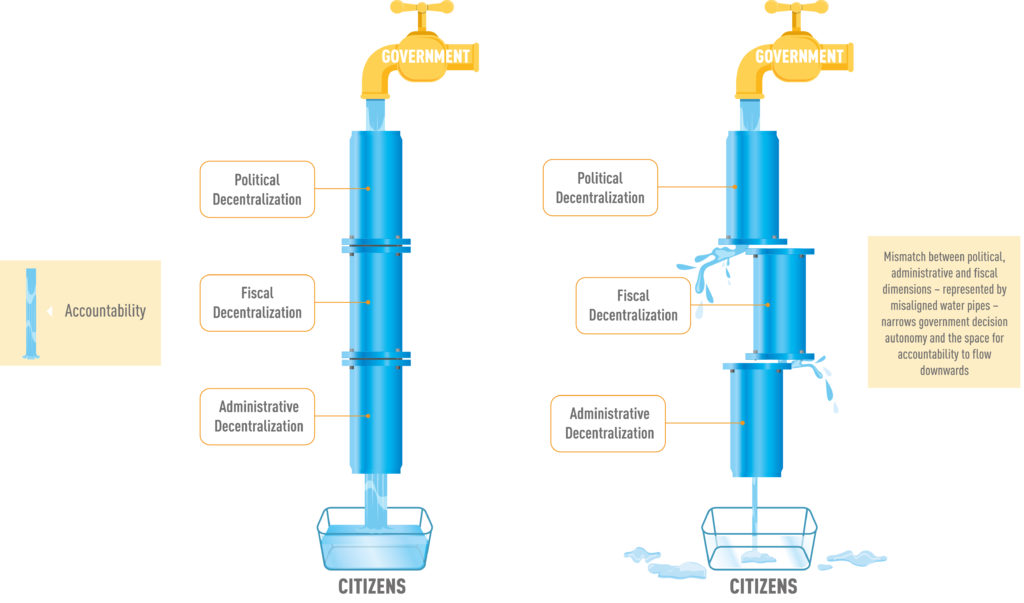

Local governments require political, administrative and fiscal authority to capitalise on their informational advantage and adequately respond to citizens (See Pranab, 2002 and Oates, 2005). However, these dimensions also need to be aligned – like segments of a pipe – if local governments are to be incentivised and able to be accountable to citizens.

Without sufficient authority, local governments are unlikely to be able to respond to citizens’ demands – even if they are politically incentivised to do so – and citizens have less reason for political participation. It is, therefore, important to distinguish between the mere shifting of workloads to lower level offices and the appropriate balance of political, administrative, fiscal authority of local governments

Figure: (Mis)alignment and accountability

The study

Responding to these concerns, our new report (Valley et al.) explores the institutional context of reforms and decision-making of local governments as it relates to road investment in Myanmar. The roads sector is the most fiscally decentralised and accounts for the largest share of sub-national budgets. Road spending therefore provides an important example of regular interactions between the central and sub-national governments – providing a basis from which lessons can be drawn to guide future decentralisation reforms.

Findings

The study’s findings suggest that:

- The unstructured nature of decentralisation reforms in Myanmar means that these dimensions are only partly aligned so far.

- Imbalances exist across the political, fiscal and administrative dimensions of decentralisation, which creates uncertainty and weakens local authority.

- In the roads sector, these misalignments are acute, resulting in:

- ambiguous divisions of responsibilities for roads between levels of government,

- highly fragmented administration across different government agencies,

- blurred distinctions in administrative accountability, and

- mixed financial responsibility for certain types of roads.

Implications:

- These uncertainties compound weak budgeting process and contribute to an opaque and politicised decision-making process in the early parts of the project cycle.

- In the absence of a systematised project selection and appraisal processes, space is created for individual “VIPs” to exercise their own authority, commensurate with their relative bargaining power in the local context.

Whether good outcomes are achieved through this arrangement is debatable:

- Local authorities may well be better informed about balancing local needs in the specific cultural context, particularly in conflict-sensitive areas.

- However, when project selection decisions are ceded to lower levels of government with fragmented authority and opaque decision-making process, greater space is potentially created for elite capture.

- It also risks damaging the emergence of local democratic accountability, without which the hypothesised benefits of decentralisation are likely to be lost.

What’s next?

Further reforms are currently underway in the roads sector that have the potential to reduce fragmentation and increase decentralisation, however there are some important unanswered questions:

- Some responsibility for funding works on rural roads is being shifted to sub-national governments. There is currently no expectation of a corresponding increase in sub-national revenue raising powers or intergovernmental fiscal transfers. This risks adding more fiscal pressure to relatively small state and region budgets. It is unclear how sub-national governments will fund rural roads and implement the centrally defined rural roads strategy.

- It is also unclear whether this change is an effort in greater decentralisation or simply a shift of workloads to the lower level offices.

As Myanmar continues on its path towards more decentralised governance, reforms should aim to build more sub-national autonomy and transparency in the decision-making process. In the near term, they could include pursuing further decentralisation – to align decision-making authority – by:

- experimenting with administrative models;

- introducing appraisal tools and data requirements in the budgeting process;

- formalising financial arrangements for national roads;

- earmarking revenue to finance rural roads; and

- strengthening accountability by bringing citizens closer to the decision-making process.

References

Bardhan, Pranab and Mookherjee, Dilip (2005). “Decentralisation, Governance and Accountability: Theory and Evidence”, Journal of African Democracy and Development, Vol. 1, Issue 2, 2017, 1-16, for the “Handbook of Economic Corruption”, edited by Rose-Ackerman, Susan and Elgar, Edward. Accessible: https://eml.berkeley.edu/~webfac/bardhan/papers/BardhanDecent,Corruption.pdf

Bardhan, Pranab (2002). “Decentralization of Governance and Development”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 16, Number 4, Pages 185–205. Accessible: http://people.bu.edu/dilipm/ec722/papers/28-s05bardhan.pdf

Nixon, Hamish et al. (2013). “State and Region Governments in Myanmar”, The Asia Foundation and Centre for Economic and Social Development. Accessible: https://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/StateandRegionGovernmentsinMyanmarCESDTAF.PDF

Oates, Wallace E (2005). “Toward A Second-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism”, International Tax and Public Finance, 12, 349-373. Accessible: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9

Valley et al. (2018). :Where the rubber hits the road: A review of decentralisation in Myanmar and the roads sector”, Renaissance Institute and the International Growth Centre.