How women can improve resilience and productivity of vulnerable households in Pakistan

In this IGC project, we look at evidence from Pakistan to understand the developmental and poverty outcomes of female labour force participation, particularly in low-income and vulnerable households. This is done in the context of informing a concessional finance programme targeted at vulnerable households. However, our findings yield broader results, suggesting that if challenges to female workforce participation are addressed, then developmental and productivity benefits could accrue at the national level, well beyond the programme.

Around 52% of the entire population in Pakistan is vulnerable to falling back into poverty. The Government of Pakistan invested PKR 1.4 trillion in Kamyab Pakistan Programme (KPP) launched in October 2021 to support income growth of small firms and farms through concessional finance and health insurance, to address this vulnerability that lurks behind the corner of every economic shock.

We analysed the sources of vulnerability with a slightly different lens, focusing on environmental risk factors affecting health and women’s contribution to household income. Existing data and papers were reviewed to better understand Pakistan’s current health burden linked with environmental risk factors and the situation with respect to gender inclusion, with a particular focus on vulnerable, low-income households. Here we focus on the latter.

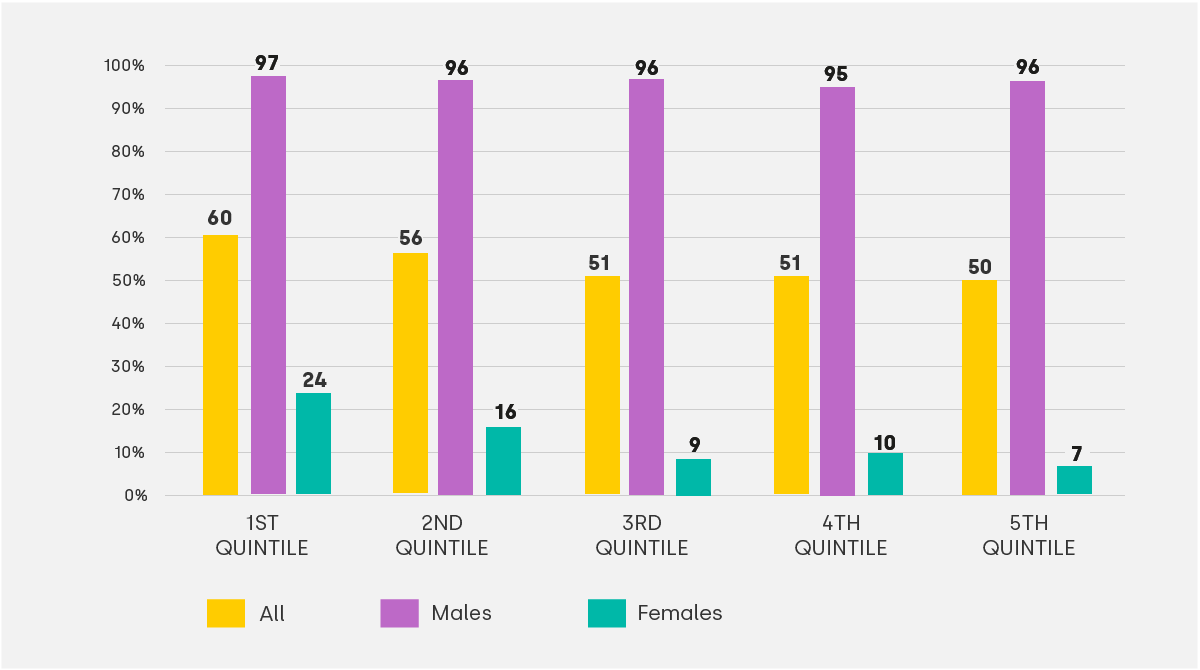

Pakistan’s female labour force participation is among the lowest in South Asia (21% in 2019), and so Pakistan loses out both in terms of untapped productive potential and the broader development gains and resilience that comes with women wage-earners in the household. In general, while labour force participation for men is high, women’s participation is substantially lower. There is also considerable variation across income quartiles, ranging from 24% for women from the lowest quartile to only 7% for women from the highest income quintile (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Female labour force participation by income quintile

Note: The graph plots female labour force on the y-axis and income quintiles– disaggregated by gender– on the x-axis. Source: Cho and Majoka (2020)

Data suggests that women from vulnerable households work because they need to augment income. Nearly a third (33.75%) of the households in Pakistan have more than one income earner, of which nearly half (43%) have at least one earning woman in the family. Multiple-earner households report a significantly higher monthly income: an average of PKR 34,000 compared to PKR 14,000 earned by single earner families. Multiple-earner households where women also work earn PKR 5,000 more than single-earner families (PSLM 2019-2020, based on authors’ calculations). This may be because women tend to engage in informal, often low-paid work and may not be compensated at the same rate as men.

The developmental impacts of female employment

Female employment has proven developmental impacts, both for women themselves and for their dependents. For instance, women who work in Pakistan are more likely to have a say in household consumption decisions and their own health decisions. Similarly, when women are part of household decision-making, households tend to spend more on young girls’ education than the average household (Data from Pakistan Rural Household Surveys 2014, 2016, 2017).

Societal norms may discourage women from working as household income rises and the need to augment household income decreases. Yet, when compared to households where women have the only business, when women set up a business in a household with other business(es), evidence from Punjab suggests that overall household income is greater, and businesses are larger with women expressing a greater willingness to take risks and experiment with new business products (based on authors’ calculation) .

Challenges to female labour force participation

Research in Pakistan suggests that major challenges to women’s participation in the workforce include: (i) financial exclusion and lack of access to finance; (ii) inadequate skills, including low digital literacy; (iii) lack of safe transport options; (iv) discrimination in the labour market); and (v) low returns to education. The overarching constraint appears to be social norms, with women requiring permission to work from other household members (including leaving the home) and some work being considered inappropriate or unsafe for women.

This suggests that a more concerted and broader push to encourage greater female participation in the labour force is important to improve national productivity and help shift mindsets about women in the workforce. One estimate suggests that closing this gender gap in labour force participation could lead to a one-off 30% boost in GDP.

While the focus is often on financially incentivising women to train or look for work, lessons from Pakistan and around the world suggests that such incentives alone are not enough. For instance, the Punjab Skills Development Fund found that the impact of technical training offered to women was manifold when the trained women were also linked with sales and other market agents to sell their products. Similarly, while women often lack finance for their business, microloans have failed to have a transformative impact on sales and profits of female-led businesses. On the other hand, financial products that allow women flexibility in repayment and reduce the likelihood of misappropriation of funds by other household members can be important factors impacting the welfare of the recipients.

Unlocking women’s productivity would require a policy intervention on multiple fronts. In addition to skills development and access to finance, equitable pays, quality childcare options, and safe transport to work can reduce concerns expressed by women and their household members, broadening the scope of work that they can engage in. Information interventions at the community level can reduce stigma around working women. A broad push should also include gender targets, KPIs, monitoring, and an oversight mechanism in all loan programmes, including the KPP.

In conclusion, addressing gender disparities in the labour force will benefit vulnerable households disproportionately in Pakistan. This suggests that any loan programmes focused on vulnerable households, such as KPP, can be made more effective by including gender KPIs. However, the benefits to increasing female labour force participation go well beyond such programmes, in terms of increased national productivity and development gains.