How Zimbabwe can embrace the future of work

Local contexts must be given as much prominence as global in the debate about the future of work, argues LSE’s McDonald Lewanika.

The future of work is at the centre of the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) centenary conversations for 2019 when it turns 100. This multi-sector global debate focuses on four conversations: work and society; decent jobs; organisation of work and production; and the governance of work. The emerging consensus is that the exponential pace of automation and other technological advances are the leading global trends informing the future of work. There is also an acknowledgement that the future of work is being influenced not just by the rise of emerging markets, demographic transitions, and global value chains, but also by social concerns such as changes in work consciousness, rising inequality, climate change, and rapid urbanisation. Despite this, there is disagreement on their expected impact in various contexts.

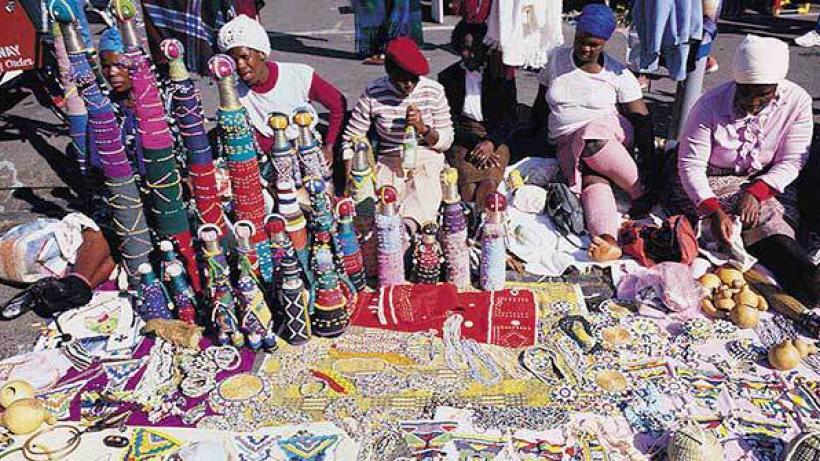

Credit: Gauteng Department of Economic Development

Credit: Gauteng Department of Economic Development

While some see technological advancement as promoting profit and progress, others view artificial intelligence and automation as heralding Armageddon and possible subjugation. When considered through a positive lens, optimists see technology reshaping labour markets, making them more digital, online, mobile, and more efficient. Automation and machines serve people, helping them to work less, produce more, specialise, and earn more, resulting in a better work-life balance. On the other hand, sceptics see automation as putting people out of work at scale, with the few jobs left being casual and informal, resulting in more glaring inequalities between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. Whatever the case may be, notwithstanding these ‘observable dynamics of change and some very harsh realities, the future of work is what we will make it,’ argues Guy Rider, Director-General of the ILO.

Despite the nomenclature, the question of the future of work is not a futuristic academic conversation. It is relevant today, and we feel its effects in our professional, political, social, economic, and personal spaces. While global discussions on the future of work also have tremendous appeal and are heavily sponsored by international actors and capital, conversations in the developing world acknowledging global trends while giving importance to local contexts must start to take place. The latter have so far received scant attention.

For Zimbabwe and the bulk of sub-Saharan Africa, these contextual realities comprise underdeveloped industries, premature deindustrialisation, and an underemployed and untrained labour force mostly located in the “precarious” informal economy, where gender gaps in both access to work and remuneration persist. For instance, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Index (GCI) gives Zimbabwe’s capacity to innovate, business sophistication, labour market efficiency, and education and training a comparatively low rating. While there may be real concerns about these measures and how accurately they reflect Zimbabwean reality, they identify some deficiencies, which conversations on Zimbabwe and the future of work need to address. Additionally, variations between contexts – as suggested by the GCI ratings – entail that strategic conversations on the future of work in Zimbabwe need to be different from debates on the future of work in the Global North where technological advances, industry, and global competitiveness are supposedly at the ‘higher end’ of the spectrum. This approach would also apply to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

For a country like Zimbabwe, the conversation on the future of work has to be informed by the state of the economy, human development, and attendant gender disparities. Given that over 94 per cent of Zimbabweans work in the informal sector, this sector should feature as an integral part of the country’s development and as the bastion of work, production, creativity, and innovation, rather than viewing it solely as a potential tax base for the state or criminalising and penalising its participants. Zimbabwe’s high rate of informality indicates that the future of work conversation in the southern African country may need to centre on dealing with decent work challenges. In this respect, conversations should aim to ensure that technological accelerators and economic regulation do not unduly destroy livelihoods in the name of efficiency and progress, and do not fortify existing social inequalities.

Zimbabwe, like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, faces a myriad of challenges, which include natural (geographic) and political issues (policy choices and global economic and geopolitical dynamics), as well as challenges stemming from political and economic colonial legacies. Dealing with these challenges as part of preparing for the future of work will need conversations on visionary, long-term integrated planning. Through such an integrated future focus, countries like Zimbabwe can manage staggered economic transitions that include improving education and building technological capacity, transitioning production and jobs from the primary sectors of agriculture and mining possibly to light mining and agro-industries based on value addition, and further heavy industrialisation. This can also facilitate transitions of jobs of the future from informality to formality.

Zimbabwe, like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, faces a myriad of challenges, which include natural (geographic) and political issues (policy choices and global economic and geopolitical dynamics), as well as challenges stemming from political and economic colonial legacies.

The future of work in Zimbabwe and beyond should be the subject of continuing discussions, planning, and action of a broad range of societal interests at local and global levels, beyond celebrations and events. Apart from traditional ILO social partners such as organised labour, the private sector, and government, collective conversations on the future should include the youth and women, who are both the primary actors in the informal economy as well as the biggest stakeholders in the future given current demographic transitions. Such a process can allow for reflections on the future of work that locate the roles of the main societal sectors and may need to consider the following issues:

- Transformation of the education system, going beyond ensuring access to enhancing recipients’ innovation capacities and their global competitiveness through quality, fit for purpose curriculums.

- Political and economic institutional credibility challenges that impede local and international investment into Zimbabwe’s productive sectors, which can produce decent work.

- Policies and measures that support entrepreneurs and innovators in the informal sector, and aid a transition of the sector’s participants from informality to formality.

- Private sector investment in and promotion of innovation in the firms of these entrepreneurs as well as in the informal sector through sponsoring and supporting the incubation of ideas there.

- Making informal economy actors part of the value chains of industry, while also investing in curriculum development and research in secondary and tertiary institutions of learning.

- Preserving spaces for collective action and organised labour and as a corollary the decent work agenda and the sacrosanctity of social justice.

The above issues highlight the interconnected nature of challenges central to the future of work and all four ILO centenary conversations. Conversations and actions taken to shape the future work must address these issues, pivoting towards decent work deficits and possible threats to social justice. This will be of fundamental importance if Zimbabwe and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa are to counter the looming threat that the fourth technological revolution could foster the advancement of a few while banishing millions to poverty in a highly unequal world.

This piece has been originally published on the LSE Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa blog and extracted from a draft discussion paper on Zimbabwe and the future of work developed after a high-level debate that took place at the 2016 edition of “theSpace” in Harare on 16 September 2016. The draft discussion paper is a work in progress but is available here.