Learning to navigate a new financial technology: Evidence from Bangladesh

How do consumers learn to navigate a new financial technology? An experiment with workers from Bangladesh suggests that experience makes a difference

In the past decade, more than one billion people have gained access to a bank or mobile money account (World Bank 2017). While this shift has provided households with greater choice and autonomy, there is also widespread concern that financial intermediaries can profit by exploiting inexperienced consumers (Campbell et al. 2011, Badarinza et al. 2019).

Indeed, the available evidence suggests that financial intermediary misconduct is rampant in developing countries. Survey evidence indicates, for example, that mobile money customers are overcharged in 20% of all transactions in Ghana (Annan 2019), and in Nigeria 40% of financial agents were found to overcharge their customers (EFinA 2020).

In light of these risks, the expansion of consumer finance to less experienced customer populations has given rise to a debate about the trade-off between access and consumer protection. Some regulators argue that predatory practices are so widespread that limits should be placed on access and product features—potentially at the cost of greater financial inclusion. Proponents of lighter regulation, on the other hand, emphasise the benefits of new financial products and technologies and advocate for information-based policies that strengthen transparency and consumer awareness.

One important question at the heart of this debate is how much ’learning by doing’ occurs naturally as consumers adopt and begin to use new financial technologies on an everyday basis. Exploring this is particularly timely as payroll accounts are currently being rolled out to millions of workers worldwide in response to demands for greater supply chain transparency and contactless transactions.

Introducing a new financial technology: Payroll accounts with automatic wage payments

In our research (Breza et al. 2020), we examine this question using an experiment that introduced bank and mobile money accounts with automatic wage payments in a population of largely unbanked manufacturing workers in Bangladesh. Prior to our study, all workers in our sample received their wages entirely in cash, as is the case for approximately 85% of all employees in developing countries. We tracked workers over a period of approximately two years using surveys and administrative data and examine impacts on consumer learning and real outcomes.

In order to identify ‘learning by doing,’ our experiment was designed to vary both access to accounts and incentives to actively engage with the account. We divided workers into two treatment groups:

- Workers in the main treatment group received a bank or mobile money account with automatic monthly wage payments.

- Workers in a comparison group received an account but continued to be paid in cash.

In this way, we are able to compare workers who gain access to an identical financial product with workers whose wages are automatically deposited in their accounts facing exogenously stronger incentives to actively engage with their accounts.

We measure consumer learning using two outcomes:

- Workers’ comfort with the technology: Our first learning outcome measures whether workers start making transactions at banking and mobile money facilities outside the study locations, where assistance with transactions is not readily available.

- Learning to make direct transactions: Our second learning outcome measures whether workers learn to make send-money transactions directly from their mobile money accounts.

At the beginning of the study, participants were generally unable to complete a transaction without the assistance of an intermediary, typically a mobile money agent. This gives rise to various consumer protection risks. In our setting, we found that in more than 30% of cases, mobile money agents charged an extra fee of 2–5% of the transaction amount to provide this service – a practice explicitly prohibited by the mobile money provider. To capture consumer learning, we thus measure whether consumers learn to make transactions directly from their account, thereby avoiding the risk of illicit extra charges altogether.

Consumers become more confident and learn to avoid extra charges

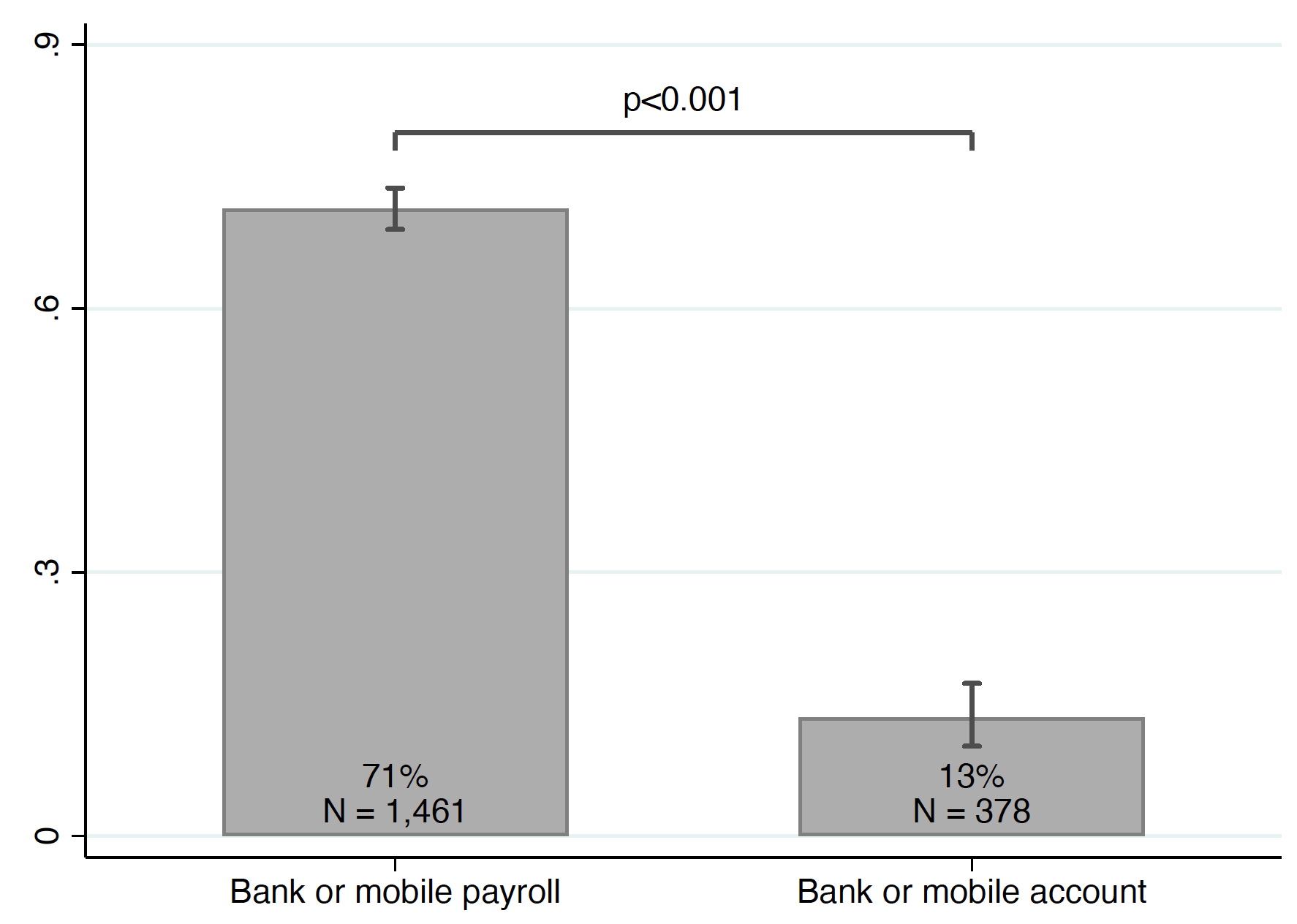

We find evidence of ‘learning by doing’ along both dimensions. Compared to workers who received an account but continued to be paid in cash, workers in the payroll accounts group become comfortable with the technology more quickly and begin making transactions in settings where assistance is not readily available. At the end of the study, workers in the payroll accounts group were 58 percentage points more likely to make a transaction outside the study locations than participants in the accounts-only group (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Learning: Transactions without assistance

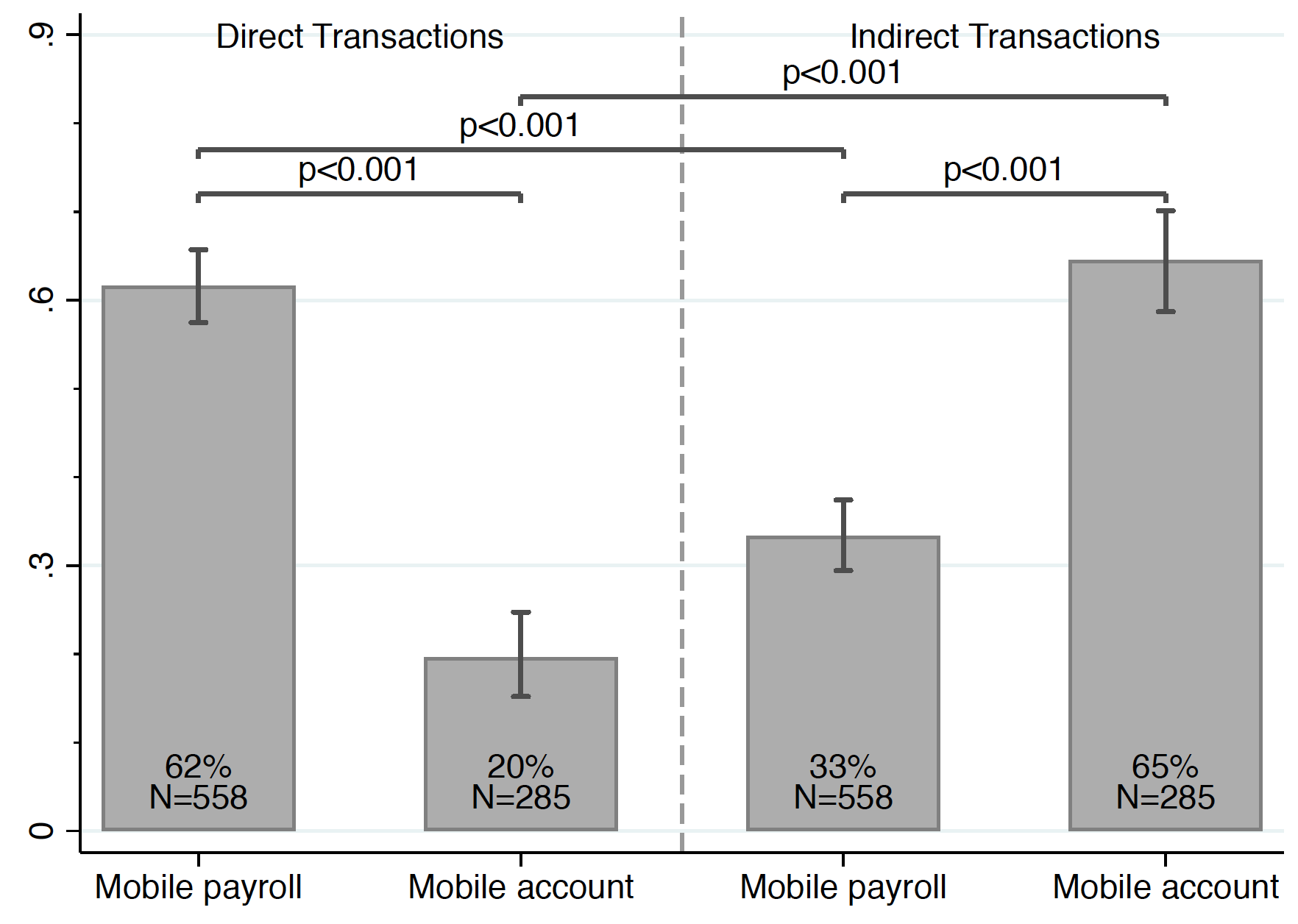

We find the same pattern of results for our second learning outcome. Compared to workers in the account-only group, workers in the payroll account group were 42 percentage points more likely to make transactions directly from their account and 32 percentage points less likely to make transactions through a mobile money agent (Figure 2). It is worth noting that the learning effects are concentrated among workers assigned to a mobile money payroll account – the newer and arguably more complex version of the financial technology, which workers trust much less at baseline than a conventional bank account.

Figure 2 Learning: Direct versus indirect transactions

Real effects: Savings, remittances, and consumption smoothing

In addition to facilitating consumer learning, payroll accounts with automatic wage payments also have direct benefits for consumers. They facilitate savings by reducing transaction costs, enable workers to have greater control over their income, and may act as a commitment device that reduces temptation spending. Consistent with these mechanisms, we find that workers in the payroll account group are 4 percentage points more likely to have any savings at endline. They are also more than twice as likely to have savings in a formal account (from a base of 25%) and are better able to weather unanticipated income shocks. Most of these effects are larger for women, who experience a greater increase in control over their own finances as a result of gaining access to a payroll account.

Externalities from consumer learning

Finally, we try to understand whether consumer learning generates positive externalities as new financial technologies are introduced at scale. That is, do inexperienced consumers benefit as the average consumer in the local market becomes more knowledgeable about the technology?

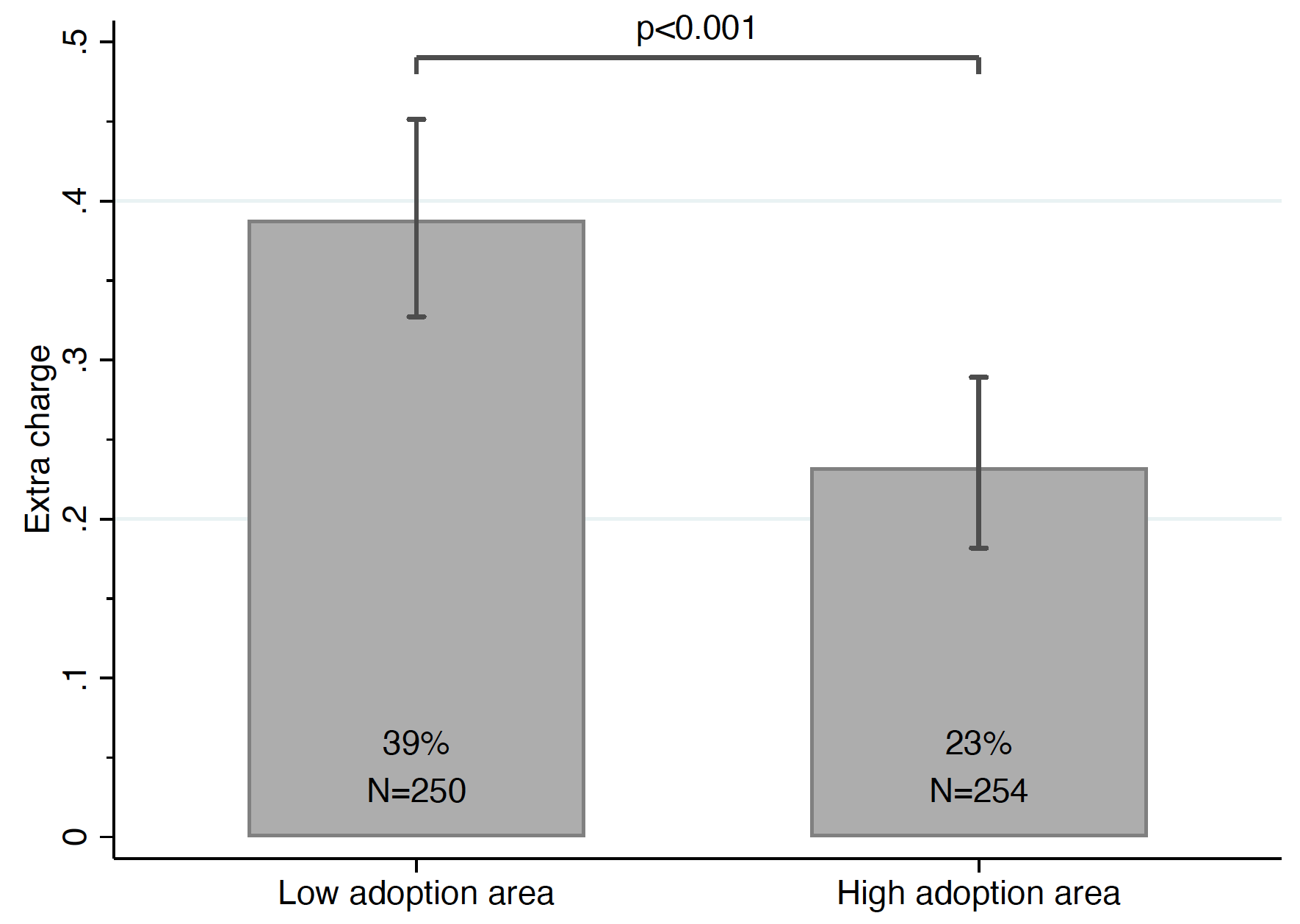

To examine this question, we conducted an audit study in which we trained workers to attempt to send money transactions at randomly assigned mobile money agents located in neighbourhoods with different levels of payroll account adoption. We then measured whether agents are less likely to overcharge consumers in areas with higher adoption of payroll accounts.

We find that the same consumer is 16 percentage points less likely to be overcharged in areas with higher (above median) payroll account adoption (Figure 3). While we cannot fully disentangle the underlying mechanism, we interpret this as suggestive evidence of positive market externalities of consumer learning inexperienced consumers are less likely to be overcharged in areas where the financial technology is more widespread.

Figure 3 Externalities from consumer learning

Who learns to use the financial technology?

While we document substantial ‘learning by doing’, our results also highlight that the ability to learn through experience is not uniform across the population. An examination of individual characteristics suggests that the ability to learn through experience is lowest among individuals with low baseline levels of literacy, financial experience, and control over household resources. These are all characteristics that correlate strongly with requiring an intermediary to access an account. At the same time, our results suggest that the same group of study participants is most likely to benefit from the traditional advantages of account ownership – namely, the ability to accumulate savings and mitigate economic shocks. Our results therefore also shed light on where traditional financial training and education interventions would have the highest marginal effect.

This article first appeared on VoxDev (you can see the original here) and is based on this IGC project.

References

Annan, F (2019), “Gender and Financial Misconduct: A Field Experiment on Mobile Money”, Working Paper.

Badarinza, C, V Balasubramaniam and T Ramadorai (2019), “The Household Finance Landscape in Emerging Economies”, Annual Review of Financial Economics 11(December): 109−29.

Breza, E, M Kanz, and L Klapper (2020), “Learning to navigate a new financial technology: Evidence from payroll accounts”, NBER Working Paper 28249.

Campbell, J Y, E J Howell, B Madrian and P Tufano (2011), “Consumer Financial Protection”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(1): 91–114.

EfinA (2020), Financial Services Agents Survey 2020 Report.

World Bank (2017), Global Findex Database.