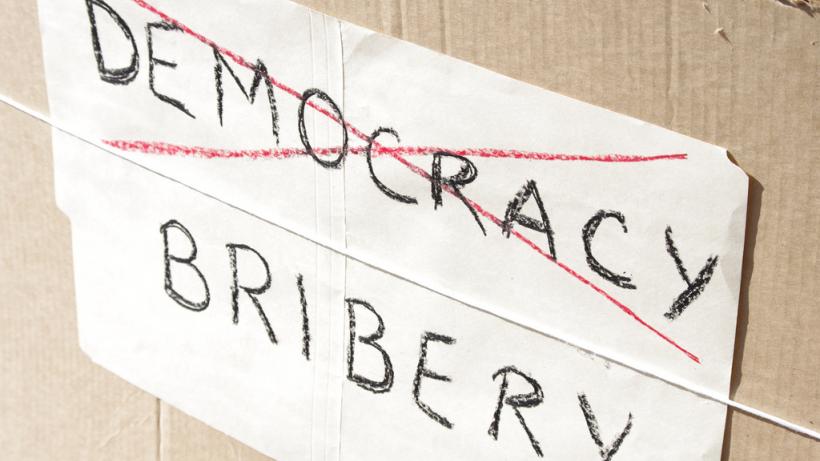

Local government corruption in Ghana: Misplaced control and incentives

Bureaucrat corruption corresponds to the control politicians have over their careers. Politicians distort processes to extract funds and garner influence. A more structured bureaucrat transfer process and the monitoring of procurement can curtail corruption.

In Ghana in early 2017, a police officer became embroiled in a conflict with a renowned Member of Parliament (MP). The police officer was attempting to close down a broadcasting company that was operating without a license. The MP attempted to transfer the officer to the hinterland for his apparent “wrong doing” in holding the company accountable. It was then revealed that the company was one of the MPs’ donors. The defiant police officer hired a lawyer, who successfully petitioned the President's advisory board to revoke the transfer. Similar cases often emerge in Ghana where local bureaucrats are transferred or threatened for holding opposing views to politicians.

Corruption: Politicians and bureaucrats

Existing theories on why bureaucrats engage in corruption focus on the numerous opportunities to be corrupt on account of limited monitoring. Alternatively, bureaucrats are said to be motivated to steal from public coffers to get wealthy or meet financial pressures from their family members.

Scholars have written less about the potential coercion of bureaucrats by politicians, the pressure that bureaucrats face to flout laws, and why bureaucrats may be willing to engage in corruption that benefits politicians, even when bureaucrats themselves do not personally benefit (or benefit only minimally).

The study: Control and corruption

The International Growth Centre (IGC) project analysed politician-bureaucrat relationships in local governments in Ghana, with the aim of documenting:

- the prevalence of corrupt procurement practices among local government civil servants, and

- the incentives that politicians and bureaucrats have to facilitate this type of corruption.

Through surveys and interviews with nearly 900 civil servants across 80 local governments in Ghana, I measured levels of corruption and investigated incentives for bureaucrats to be corrupt. The key hypothesis that was tested was whether increased levels of political control over the careers of bureaucrats is associated with higher levels of reported corruption.

Public procurement

The need to invest in public infrastructure is very apparent in Sub-Saharan Africa. To build new infrastructure, politicians and bureaucrats must plan projects, select beneficiary communities, and award contracts to firms as part of a (theoretically) competitive procurement process. Procurement transactions, like most state-led development processes, involve a series of administrative steps that are handled by professional civil servants.

Politicians have an incentive to distort procurement processes to distribute contracts to private donors or their partisan allies. In the case of Ghana, qualitative evidence suggests that politicians attempt to award contracts to firms operated by local party activists who they rely on to get out the vote for the party on election day.

If politicians want to distort procurement processes, in most cases they must work with bureaucrats to do this. In an era where bureaucrats are selected for professional positions, for the most part, by merit, the question becomes why bureaucrats would be willing to forgo their professional integrity and undermine competitive procurement processes for the benefit of politicians?

Measuring corruption

Corruption, and one’s engagement in it, is a sensitive topic. When topics are sensitive, respondents have an incentive not to answer truthfully because they fear repercussions or because they find it embarrassing to admit to the truth.

To promote honest responses, I adopted a range of techniques:

- I allowed bureaucrats to self-administer their responses to sensitive questions.

- Questions were designed to provide respondents with plausible deniability: To measure bureaucrats' engagement in corruption, I use a randomised-response (RR) survey method. The randomised-response technique aims to solicit honest answers about sensitive behaviour, such as corruption, through inducing random noise into the responses of individuals (Blair, Imai and Zhou, 2015). Importantly, research shows that RR-techniques can recover unbiased estimates of sensitive outcomes that researchers are trying to measure (Rosenfeld, Imai and Shapiro, 2015).

- The “forced-response" RR-method design was employed: Researchers give respondents a randomisation device, such as a die or a coin, which they use to determine whether they should give an honest or predetermined ("forced") response. When using a die, the enumerator does not observe what the respondent rolls. By introducing random noise to responses, individuals are protected because enumerators are unable to know if a positive response is because of the roll or because it is their honest answer.

Political control over bureaucrats: Measuring discretionary oversight

I operationalise the discretionary oversight that politicians have over bureaucrats as the ability of politicians to transfer bureaucrats to undesirable posts. I focus on transfers because Ghanaian politicians cannot fire bureaucrats who resist their demands.

Variation in politicians' ability to transfer bureaucrats results from both politicians and bureaucrats having differential access to administrative higher-ups who have the final say on transfers. Transfers are a powerful tool of control in low-income countries because of significant subnational variations in levels of development and hence, quality of life.

Results:

- Widespread abuse in procurement with nearly half (46 percent) of the surveyed bureaucrats admitting that public contracts in their assembly are awarded to contractors in exchange for campaign finance.

- Evidence that bureaucrats facilitate corrupt procurement in response to threats from local politicians of being transferred to less desirable districts in the country.

- Bureaucrats’ propensity to grant contracts to partisan contractors varies according to the extent to which politicians can control bureaucrats’ careers through transfers.

- Bureaucrats are more likely to report abuse in public procurement when they perceive their mayor as easily able to transfer them.

- Specifically, when bureaucrats perceive their local mayor (District Chief Executive) has no influence on transfers, 34.3% report corruption in procurement. This figure increases by 15 percentage points to 49.8% when bureaucrats say the mayor has a lot of control over transfers.

Implications: Incentives and power

The central argument here is that local bureaucrats in Ghana engage in corruption because politicians retain discretionary control over their careers through their ability to transfer them. Therefore, the introduction of meritocratic hiring is not enough to protect against widespread corruption because unchecked politicians hold strong incentives to distort administrative processes. These incentives stem from politicians' need to generate funds to finance political parties and election campaigns.

The results call into question the traditional view in the literature that giving politicians greater control over bureaucrats improves policy outcomes. While granting politicians oversight tools (such as control over bureaucratic transfers, salaries, or promotions) may align bureaucratic incentives with politicians' goals, it can weaken overall government accountability to the citizenry by allowing politicians to threaten or bribe bureaucrats to enable corrupt activities.

Recommendations:

- Bureaucrats should be posted to work in districts for a fixed number of years, with the transfer process centralised in the hands of the Local Government Service Secretariat (LGSS). A more structured transfer process would allow bureaucrats to resist pressures from local politicians to undermine competitive procurement processes.

- Local mayors in Ghana should be removed as the chairs of district tender committees. This would help to minimise their influence on the selection of contractors.

- Members of the local procurement committee (District Tender Committee) should declare their assets to the Auditor General upon taking their position. Ghana’s Local Government Act 462, 1999 demands that members of the District Tender Board declare their assets to the Auditor General within three months of taking office. This practice is rarely followed. Such practices should be institutionalised to guard against politicians and local bureaucrats making private gains from the distribution of public contracts.

- To ensure that local governments award contracts to experienced contractors, the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MoLGRD) should monitor contracts awarded by local governments.