Mining taxation policy in Zambia: The tyranny of indecision

Instability, massive increases and novel taxes not seen anywhere in the world’. That is the way the outgoing Zambia Chamber of Mines President, Nathan Chishimba, described the new tax measures targeted at the mining sector in the 2019 budget. The Zambian government has charged that these new measures will ensure that the sector is paying its fair share of taxes, but the mining firms have pushed back, declaring the new set of taxes will make them loss-making entities and render Zambia un-investable.

Mining taxation policy has been thrust back into the fore in Zambia’s policy debates. At the heart of this is the question of how a government can maximise revenues from its extractive sector without compromising mining firms’ ability to make profits. Equally important is whether the mining firms that operate in the developing world are contributing their fair share in their respective countries. In this blog, the first in a two-part series, we begin by examining the policy stance of the Zambian government by peering into insights these new changes reveal about mining taxation policy in Zambia.

Mining taxation policy in Zambia is unstable

Zambia’s policymaking in the area of mining taxation has been characterised by frequent policy changes and reversals. In the 2019 budget, slightly over half of the revenue measures proposed were directed at the mining sector representing yet another seismic shift in mining taxation policy. By one estimate, Zambia on average has had one tax change every 18 months since 2001 (Zambia Chamber of Mines 2018).

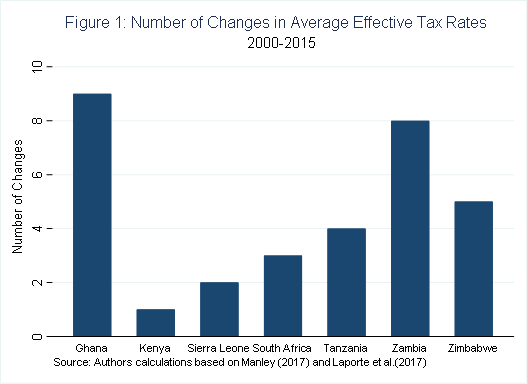

This is frequent even by sub-Saharan African standards. The Average Effective Tax Rates (AETR)[1] applicable to the mineral sector in several resource rich sub-Saharan African countries over the period 2000 to 2015, reveal that Zambia ranks second after Ghana in terms of the frequency in changing measures.

This does not appear to be a recent problem. Table 1 presents a summary of changes in the mining tax regime since independence. Fiscal stability emerges as a major challenge with nine out of the eleven regimes rated as lacking fiscal stability. The authors do not define what they mean by fiscal stability. However, at a minimum a fiscally stable regime should be designed with in-built flexibility to both automatically capture increased government revenue when copper prices rise and automatically reduce the tax burden for mining firms during periods of low copper prices without requiring frequent legislative changes (Manley 2013).

Table 1: Features of the major mineral tax regimes in Zambia: 1964-2016

| 1964 | 1966 | 1970 | 1983 | 1986 | 2000 | 2008 | 2009 | 2012 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Royalty | 13.5 | 13.5 | 0.6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6-9 | 4-6 | |||

| Export tax | 40 | 4-8 | 13 | ||||||||

| Mineral tax | 51 | 51 | 51 | ||||||||

| Corporate Income Tax | 37.5 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Variable income tax | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |||||||

| Windfall tax | 25-75 | ||||||||||

| Capital allowance | 5 | 5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 25 | 100 | 100 | 25 | 25 |

| Reference price | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ring fencing | No | No | No | No | N | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Loss carry-forward | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tax haven owner | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Share of govt ownership | 51 | 100 | 100 | 10-20 | 10-20 | 10-20 | 10-20 | 10-20 | 10-20 | ||

| Fiscal stability | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

Source: Adapted based on Lundstøl and Isaksen (2018). All figures in percentages.

It is, however, easy to cite policy instability as a major problem in developing countries which can easily become a simplistic description of a complex problem. The Natural Resource Governance Institute, for instance, reports that in many resource rich countries, frequent policy changes are common in their tax regimes. Further, at times these changes do not always have a negative impact on variables such as investment. The evidence on Zambia is mixed. In Zambia, the mining sector dominates FDI inflows accounting for about 60% of Zambia’s FDI inflows and investment into the sector has continued to flow (Phiri 2011). Sachs et al (2013) find that in the countries they study, investment continued rising despite the rhetoric of companies in the face of tax increases. Manley (2013) surmises that Zambia’s case may be similar with an indication of increased investor confidence over the period until 2015 although it is unclear as to whether this will continue to be the case.

Why policy changes are important

What is often crucially important are the reasons underlying a policy change. A policy change initiated to take advantage of a boom in commodity prices for instance can be perfectly justifiable. In the Zambian case, the 2019 changes seem to flow from misguided motivations. A non-too-hidden clue is reflected in the country’s deteriorating fiscal position in the recent past. The fiscal deficit in recent years has been high. In 2015 the deficit on a commitment basis exceeded 12% of GDP before reducing slightly to 9% in 2016 (IMF 2017). It increased again to 10% of GDP in 2018, fully entrenching the trend of excess expenditure over revenue (IMF 2019). The Zambian government, in an attempt to return to ‘fiscal fitness’, may be prioritising short-term mobilisation of revenue from the sector, at the expense of building a sustainable fiscal regime with consistency over time.

A tax administration struggling to effectively and efficiently collect tax

The instability in mining taxation policy in Zambia seems to signal constrained capacity in the revenue administration’s ability to collect revenue from the sector. Arguably problems of tax administration are sought to be addressed by changes in tax policy. Thus, the multiplicity of policy changes could potentially be a symptom of this. This is an area that needs further research. The shift to an increased reliance on mineral royalty versus profit-based taxation is a clear indication of this. Mineral royalties are much easier to collect and require less effort as opposed to a profit-based tax system that requires more sophisticated audit skills to verify mining firms’ reported profits (or losses) (Sunley and Thomas Baunsgaard 2001).

However, what Zambia needs to focus on is building the ability of its revenue authority staff to understand not only the mining sector but matters to do with Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEEPs). This might entail looking beyond traditional methods of training and finding innovative ways of transferring skills to inspectors so that they keep adapting to the changing business environment. As the World Bank (2015) aptly put it, ‘Without solid tax administration, risk assessment, auditing, environmental monitoring, and regulatory capacity, even the best designed policies will not work.’

Mining taxation policy changes often come with unintended consequences

What may have escaped policymakers is the unintended ways these tax changes will affect the economy. For example, the removal of VAT in order to eliminate refund payments to the mining sector will affect businesses and consumers outside of the mining sector acutely. VAT replaced sales tax in the majority of countries precisely to eliminate the negative effects of sales tax. These effects include an increase in prices for consumers due to price cascading (Gerard and Naritomi 2018), a distortion in production efficiency with firms vertically integrating to minimise the effect of the tax (Keen 2016), and a reduction in tax revenue due to a rise in collusive evasion among firms (Garard and Naritomi 2018).

Some of the other changes further conflict with other national development goals. A diversified and export-oriented mining sector is one such goal articulated in Zambia’s Seventh National Development Plan. Contrary to spurring on diversification from large-scale copper mining, the switch from VAT, the mineral royalty changes, and the 15% export tax on precious metals and manganese, will negatively affect the emerging Gold and Manganese sectors - two nascent sectors - mostly in the hands of small-scale Zambian miners. This might push some of them back into informality and smuggling and subvert the goal of diversification.

While policy limitations exist on the side of the state it is equally important to look at the contribution of the mining sector to Zambia’s development story. We explore this in part 2.

References

Gerard, F and J Naritomi (2018), “Value added tax in developing countries: Lessons from recent research”, IGC Growth Brief Series 015, London: International Growth Centre. Accessible: https://www.theigc.org/publication/value-added-tax-developing-countries-lessons-recent-research/

International Monetary Fund (2017), “Zambia: 2017 Article IV consultation — press release; staff report; and statement by the Executive Director for Zambia”, IMF Country Report 17/327, October 2017. Washington, DC: IMF.

International Monetary Fund, (2019), “IMF staff completes 2019 article IV visit to Zambia”, IMF Press Release 19/130, April 2019. Washington, DC: IMF. Accessible: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/04/30/pr19130-zambia-imf-staff-completes-2019-article-iv-visit?fbclid=IwAR32rwPVGrIrRLuxOpeRz_nkB-8LB1QdgVZNllxZusO6Sg9QM-PUfIxEV-Q

Keen, M (2016), “Taxation and development—again”, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, Fiscal Affairs Department.

Laporte, B, C de Quatrebarbes, Y Bouterige (2019), “Mining taxation in Africa: The gold mining industry in 14 countries from 1980 to 2015”, halshs-0154536, Accessible:

Lundstøl, O and J Isaksen (2018), “Zambia mining windfall tax” UNU WIDER Working Paper 2018/51.

Lusaka Times (2018), “2019 budget will break the back of Zambia’s economy, warns Chamber of Mines”, Accessible: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2018/10/04/2019-budget-will-break-the-back-of-zambias-economy-warns-chamber-of-mines/

Lusaka Times (2018), “First quantum minerals warns that it will cut production at sentinel once sales tax kicks in”, Accessible: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2018/12/19/first-quantum-minerals-warns-that-it-will-cut-production-at-sentinel-once-sales-tax-kicks-in/

Manley, D (2017), “Ninth time lucky: Is Zambia’s mining tax the best approach to an uncertain future?’, Natural Resource Governance Institute”, Accessible: https://resourcegovernance.org/analysis-tools/publications/ninth-time-lucky-zambia%E2%80%99s-mining-tax-best-approach-uncertain-future

Manley, D (2013), “A guide to mining taxation”, Zambian Institute for Policy Analysis and Research, Lusaka.

Ministry of Finance (MOF) (2018), “2019 budget address by Honourable Margaret D. Mwanakatwe, MP, Minister of Finance, delivered to the National Assembly on Friday 28th September 2018.” Government of the Republic of Zambia, Lusaka.

Phiri, W (2011), “FDI in Zambia’s mining and other sectors: Distinguishing drivers and implications for diversification”, Macroeconomic and Financial Management Institute of Eastern and Southern Africa (MEFMI), Working Paper, Harare.

Sachs, L, T Perrine and M Jacky (2013), “Impacts of fiscal reforms on country attractiveness: Learning from the facts”, In Yearbook on international investment law and policy 2011–2012, ed. Sauvant, K, 345-386. Oxford: Oxford Press.

Sunley, E, T Baunsgaard and D Simard (2001), “The tax treatment of the mining sector: An IMF perspective”, In World Bank Workshop on taxation for the mining sector (April 4-5, 2001), Washington DC.

World Bank (2015), “Zambia economic brief fifth economic brief: Making Mining Work for Zambia”, The World Bank, Washington.

Zambia Chamber of Mines (2018), “’Taxing the mining sector’ A report”, Lusaka.

Zambia Revenue Authority (2018), “2019 budget overview of tax changes”, Zambia Revenue Authority, Lusaka.

[1] AETR measures the state’s share of income over the lifetime of a mining project and is a way of measuring and assessing different taxation regimes overtime.