Overcoming the middle-income trap: Policy priorities for Latin America

Boosting innovation, infrastructure and education policies, while improving institutions and finances can help the region reach the high-income range.

During more than half a century, most Latin American countries have been unable to significantly reduce the income gap with advanced economies and breakout from the middle-income range. Since the 1970s, this gap has been increasing. In Latin America and the Caribbean, only Trinidad and Tobago (since 2006), and Chile and Uruguay (both since 2012) have achieved high-income status (World Bank, 2018).

The long period of middle-income status in Latin America contrasts to that of European and Asian countries. These economies reached the status of high-income during the last half of the 20th century, surpassing middle-income defined in the range of USD PPP 2.000 - 11.750 in 1990 constant levels (following Felipe, Kumar and Galope, 2017) in about three decades.

The policy question therefore remains, what are the policy priorities Latin American countries should target to transition from middle to higher income? Our analysis aims to shed some light based on previous experiences from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and other emerging economies from Asia.

The middle-income trap

The middle-income trap is a recurrent empirical pattern when gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth slows down once the country approaches an intermediate level of development. The literature has identified the inability of the economy to adjust to new sources of growth, based on capital- and skill-intensive manufacturing and service industries, as the cause (e.g. Kharas and Kohli, 2011).

Economies that do manage to successfully transition have a set of requirements, which are not easy to achieve or co-ordinate. These include:

- skilled workers,

- a favourable investment climate,

- a developed system of national innovation,

- and a macroeconomic and institutional environment conducive to entrepreneurial activity.

Setting policy priorities: An empirical approach

In our recently published paper, ‘No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America’, we set out the policy changes needed to adjust new sources of GDP per capita growth and breakout from the middle-income trap.

Methodology

We test a wide set of variables from various strands of the literature on productivity and economic growth covering:

- macroeconomic indicators,

- tax structures,

- education attainment,

- openness and trade,

- financial development,

- institutions,

- demographics

- and income quality.

Our exercise is comparable with the growth diagnostics proposed by Hausmann, Rodrik and Velasco (2005), which focus on low social returns due to:

- poor human capital or infrastructure,

- government failures materialised as micro or macro risks,

- low domestic savings,

- and under-development of finance.

In addition to these, we include dimensions related to productive development policies (export diversification) and social policies (migration). Similarly, we complement some policy prioritisation efforts already established by international organisations and academia (e.g. the Global Competitiveness Report by the World Economic Forum, Doing Business by the World Bank, the Going for Growth analysis of the OECD) by adding new economic, social and institutional variables; broader country coverage; providing additional estimates; and increasing the time period. Izquierdo et al. (2016), from the Inter-American Development Bank, shares the most similar approach to our study, which determined policy priorities in Latin American economies in order to transition to different income per capita groups.

A discriminant analysis of middle- versus high-income countries

To determine these policy priorities, the empirical analysis is based on 1295 estimations and identifies which of a set of variables help differentiate (i.e. ‘good discriminators’ according to Fisher, 1936) between upper middle-income and high-income countries. The discriminant analysis assigns observations (of countries in our case) to a set of pre-determined categories (upper middle-income or high-income country) through a model of group discrimination based on the previous set of observed variables.

Additionally, to take into account the specificities of development paths (Lin, 2012), we apply the synthetic control method (Abadie and Gardeazabal, 2003) to find for each Latin American upper middle-income country, the weighted average of high-income countries that best replicates its characteristics ten years before passing the threshold from middle-income to high-income.

Findings

Based on the experiences of 76 emerging economies and OECD countries, and taking into consideration countries that evaded middle-income status since the 1950s, we show that the key policy areas needed for Latin American economies to breakout from the middle-income trap are:

- better institutions (rule of law and political stability),

- education (quality of secondary education and tertiary education attainment),

- improving the investment climate in physical capital,

- capabilities (technological diffusion),

- deepening of financial markets (liquidity in the stock market and domestic credit provided by the financial system),

- and taxation.

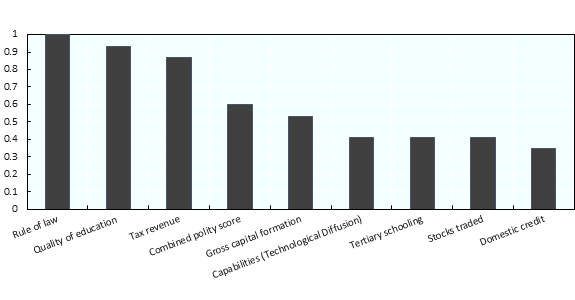

In other words, Latin American economies should boost their innovation, infrastructure and education policies, while improving the quality of institutions and securing financing for development thanks to higher level of taxes and better access to finance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap

(Ranking of importance from left to right. Average loading)

Source: Melguizo, A. S. Nieto-Parra, J.R. Perea and J.A. Perez (2017), “No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America”, OECD Development Centre Working Paper, No. 340.

Source: Melguizo, A. S. Nieto-Parra, J.R. Perea and J.A. Perez (2017), “No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America”, OECD Development Centre Working Paper, No. 340.

Applying the findings to Argentina and Colombia

The prioritisation strategy stemming from these findings should take into consideration specific policy interventions and the country context. As examples, we focus on two interesting contrasting cases in Latin America, Argentina and Colombia.

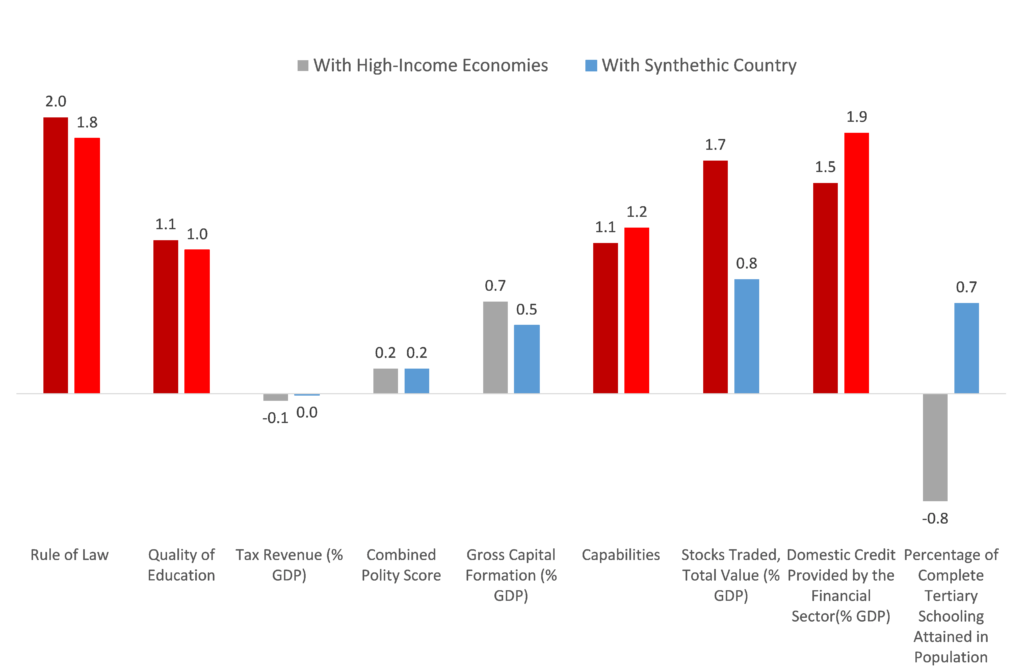

Argentina:

While Argentina has been an upper-middle per capita income economy since the 1950s, with relatively solid fundamentals, its economic development is characterised by very high volatility. Our empirical strategy points to:

- institutions,

- quality of education,

- working population,

- stocks traded in the market;

- the need to strengthen the economic complexity index (capabilities)

- and improve the domestic credit provided by the financial sector (Figure 2).

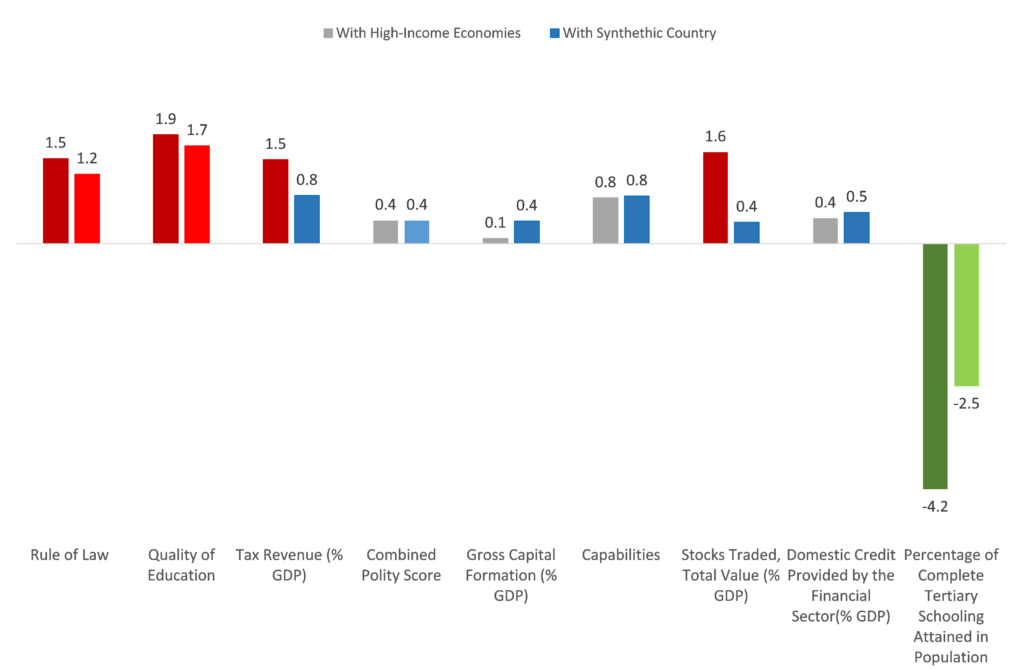

Colombia:

Colombia has shown remarkable progress, especially since 2000. Accordingly, it shows better figures than its peers in terms of tertiary education attainment (Figure 3). However, it is showing some of the limits of its development due to a pending agenda of productive diversification and investment in key inputs. Our empirical strategy suggests that policy priorities should aim for:

- improvements in the quality of secondary education,

- better institutions (efficiency and effectiveness of the State),

- a more efficient and fair tax system,

- and increasing stocks traded in the market.

Figure 2. Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Argentina

(Policy gaps vs high-income economies and synthetic country; standard deviation between 4 and 0 years with 0 a threshold year)

Note: The synthetic country is a weighted average of the following countries (weights in parenthesis): Sweden (42%), Lithuania (30%), Ireland (11%), Israel (10%), and Canada (8%). Dark red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with average higher-income countries. Red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with synthetic country.

Note: The synthetic country is a weighted average of the following countries (weights in parenthesis): Sweden (42%), Lithuania (30%), Ireland (11%), Israel (10%), and Canada (8%). Dark red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with average higher-income countries. Red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with synthetic country.

Source: Melguizo, A. S. Nieto-Parra, J.R. Perea and J.A. Perez (2017), “No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America”, OECD Development Centre Working Paper, No. 340.

Figure 3. Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Colombia

(Policy gaps vs high-income economies and synthetic country; standard deviation between 4 and 0 years with 0 a threshold year)

Note: The synthetic country is a weighted average of the following countries (weights in parenthesis): Australia (44%), Latvia (26%), Denmark (14%), Canada (11%), and Ireland (5%). Dark red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with average higher-income countries. Red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with synthetic country. Dark Green: advantage bigger than one standard deviation over the threshold compared with average higher-income countries. Green: advantage bigger than one standard deviation over the threshold compared with synthetic country.

Note: The synthetic country is a weighted average of the following countries (weights in parenthesis): Australia (44%), Latvia (26%), Denmark (14%), Canada (11%), and Ireland (5%). Dark red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with average higher-income countries. Red: gap bigger than one standard deviation with synthetic country. Dark Green: advantage bigger than one standard deviation over the threshold compared with average higher-income countries. Green: advantage bigger than one standard deviation over the threshold compared with synthetic country.

Source: Melguizo, A. S. Nieto-Parra, J.R. Perea and J.A. Perez (2017), “No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America”, OECD Development Centre Working Paper, No. 340.

Implications: Now is the time

Latin American economies are facing both an uncertain global economic scenario and an increased demand from the rising middle class for better institutions and public services, and formal jobs (OECD/CAF/ECLAC/EU. 2018). Now is the time for Latin America to consider reforms addressing potential downturns in the future, and also increasing citizens’ income and well-being.

Between 2016 and 2018 two in three Latin American citizens were in front a ballot box. Our research aims at bringing innovative tools for policy makers to prioritise economic policies that can pave the way for growth, meet the development aspirations of their societies, and ultimately lead the country to break-free from the middle-income trap.

References

Abadie, A. and Gardeazabal, J. (2003). “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country”, American Economic Review, 93 (1): 112–132.

Felipe, J., Kumar, U. and Galope, R. (2017). “Middle-Income Transitions: Trap or Myth?”, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 22(3): 429-453.

Fisher, R. A. (1936). “The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems”, Annals of Human Genetics, 7(2): 179–188.

Hausmann, R., Rodrik, D. and Velasco, A. (2005). Growth Diagnostics, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Izquierdo, A., Llopis, J., Muratori, U. and Ruiz, J. J. (2016). In Search of Larger per capita Incomes: How to Prioritize across Productivity Determinants?, Inter-American Development Bank, Working Paper Series 690.

Kharas, H. and Kohli, H. (2011). “What is the middle income trap, why do countries fall into it, and how can it be avoided?”, Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 3(3), 281-289.

Lin, J.Y. (2012). New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Melguizo, A., Nieto-Parra, S., Perea, J.R. and Perez, J.A. (2017). “No sympathy for the devil! Policy priorities to overcome the middle-income trap in Latin America”, OECD Development Centre Working Paper, No. 340.

OECD/CAF/ECLAC/EU (2018). Latin American Economic Outlook 2018: Rethinking Institutions for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017). “Going for Growth: Policies for Growth to Benefit All”, OECD Publishing, Paris.

World Bank (2018). Development Indicators Income Classifications, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Economic Forum (2016). The Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017, World Economic Forum, Geneva.