Pre-paid electricity metering and its effects on the poor

Pre-paid meters for electricity or water are spreading rapidly in the developing world. Households that switched from post-paid monthly bills to pre-paid meters in South Africa, reduced their electricity usage drastically. Given that the energy demand of households is typically relatively unresponsive to prices, the question arises as to where these reductions came from. Authors test two possible explanations and find that pre-paid metering might disproportionately increase the costs of paying for electricity for poorer households who buy electricity at higher frequencies, similar to the purchasing patterns of the poor in many domains.

Electricity demand is expected to grow dramatically in the developing world in coming decades. The governments and utility companies that need to meet this growing demand are re-thinking strategies for recovering revenue from their customers. In particular, the standard billing model -- a post-paid billing system in which a customer is charged for consumption over the past month – often results in a substantial share of bills going unpaid. Partly in response to this challenge, prepaid electricity metering is on the rise across the developing world.

In 2014-15, Kelsey Jack and Kathryn McDermott, were involved in data collection for a research project on the effect of converting customers from post-paid to pre-paid electricity metering in Cape Town, South Africa. With a pre-paid meter, households purchase electricity in the form of a voucher from the utility company, at sales points such as grocery stores, online or through mobile phones, and can use the electricity only if there is credit on the meter. This contrasts with monthly billing, where electricity is only paid post usage.

Surprising effects on purchasing patterns

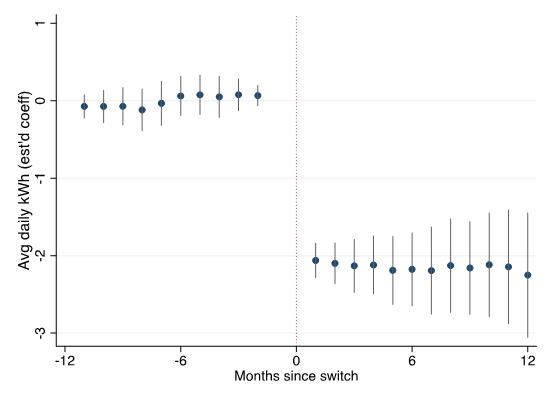

The authors of the resulting academic study (Jack and Smith 2019), documented an interesting finding: after switching from monthly bills to pre-paid meters, most households reduced their electricity usage drastically, by 14% on average. Compared with environmental policies to curb residential energy use, this is an astonishingly large effect. Moreover, the energy demand of households is typically relatively unresponsive to prices, raising questions about where these reductions come from. In this case, however, the authors found that poorer households reduced their electricity usage by proportionally more.

Figure 1: Electricity utilisation before and after switching to a pre-paid meter (Jack and Smith 2019)

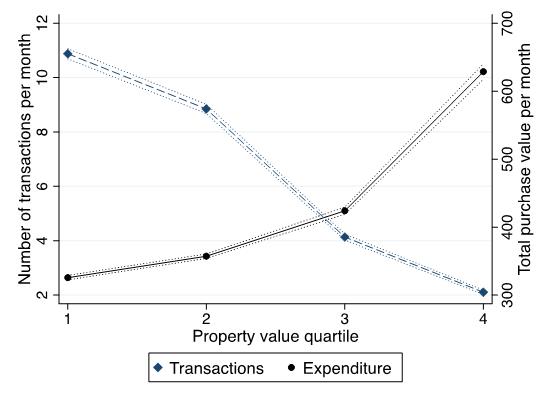

Another surprising discovery was that the poorest households began to purchase very small amounts of electricity at a time; i.e. they began purchasing electricity vouchers very frequently, sometimes daily or even several times per day. In principle, households could continue to purchase electricity almost the same way as if they received a bill, by paying a large amount once a month – however, authors found that only richer households did so.

Figure 2: Number of transactions and value per transaction for poorer vs. wealthier households, proxied by property value (Jack and Smith 2015).

Are there downsides to pre-paid meters?

Pre-paid meters for electricity or water are spreading rapidly in the developing world. They are primarily attractive to utility companies, who face lost revenue, high costs, and political barriers when enforcing bill payment on customers who struggle financially. Jack and Smith’s (2019) results suggest that the meters have additional environmental benefits by reducing residential energy use.

However, the observed purchasing patterns also suggest downsides for poorer households. Households with low meter balances are at risk of running out of electricity at times when a trip to the store is inconvenient or even unsafe. In addition, families who purchase 10 or more vouchers a month might be spending significant time and effort on meter management.

We, therefore, conducted a follow-up study to better understand why households changed their consumption patterns so dramatically, especially the poorest. This question is important, not least because these purchasing patterns are pervasive, not just in the household energy domain. Poor households tend to buy a variety of goods in small amounts and at high frequencies, often paying higher prices as a result.

Two possible scenarios: time sink or tool for consumption management

- One possible explanation is that poorer households prefer spending small amounts of money at a time, even at the cost of frequent, time-consuming transactions. Economic research suggests that households may have trouble with “self-control” (time-inconsistent preferences) and sometimes regret their choices later. With a “full” meter, it might be all too easy for example to boil another pot of tea or watch some more TV. Keeping the meter balance low might both improve self-control and reign in others in the household who do not behave responsibly. If this is the case, then the pre-paid meters and the fact that buying more electricity is not seamlessly possible, might actually help households keep their electricity use down. This, in turn, will allow them to save more money or use it for other purposes.

- However, another possible explanation is that poor households often have trouble putting together larger amounts of money, or are worried about tying up too much cash on the meter. They therefore buy smaller amounts even though it incurs the hassle of purchasing electricity more frequently. Electricity consumption goes down as a side-effect, because using less electricity is often easier than popping to the store frequently. In this case, the effort of purchasing vouchers and the resulting lower consumption of electricity creates a burden that falls disproportionately on poorer households.

A test of the two explanations: experimental evidence from Cape Town, South Africa

In order to test these two potential explanations, the authors conducted an experiment with about 800 poor households in Cape Town. In the first stage of the experiment, the households were given a relatively large transfer, either in cash, or in the form of electricity vouchers. The vouchers were either given as single vouchers or split into two, delivered three days apart. In the second stage of the experiment, the authors measured households’ “willingness to pay” to receive one form of transfer over the other, in order to infer how strongly households prefer either.

Although their results are preliminary, the authors conjecture the following from their current stage of analysis:

- Households do incur effort costs of purchasing electricity vouchers, and they dislike this cost. The typical survey respondent preferred to receive an electricity voucher over cash, even though electricity consumption increased slightly when the transfer was in kind.

- Smaller transfers do not help households curb electricity use: giving half of the transfer as a voucher right away and sending the other half to the respondent’s phone three days later did not reduce electricity use relative to the one-off large transfer. Respondents also had no preference for receiving the two small vouchers over the one large voucher, suggesting they did not find this delivery form useful for controlling their consumption better.

New technologies can differentially affect the poor

If these findings are verified in further analysis, they suggest that pre-paid metering might impose a hidden burden on poorer households. More broadly, they provide more evidence that households under financial strain spend considerable time on making frequent, small purchases of all manner of goods, in order to avoid large expenditures, and that this constitutes a real cost. This suggests another dimension to the detrimental effects of poverty: not only do the poor get to buy fewer goods, but they also spend much more time and effort in making those purchases.

This study does not provide a full welfare analysis of pre-paid meters relative to post-paid meters, because there may be other costs and benefits, for example, related to revenue recovery for the utility company. However, the results highlight one dimension of how new technologies may differentially affect the poor vis-à-vis the rich. Possible policy solutions in the electricity metering context might entail improving access to electricity vouchers, for example by setting up vending machines or phone ordering options.

References

Jack, B.K. and G. Smith (2015), “Pay as you go: Prepaid metering and electricity expenditures in South Africa”, American Economic Review 105(5), pp.237-41.

Jack, B.K. and G. Smith (2019), “Charging ahead: Prepaid metering, electricity use and utility revenue”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of the IGC’s 10 year celebration series. This blog is linked to our work on Energy for all.