Reigniting economic growth after COVID-19 in Uganda

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has come at an enormous cost to both developed and developing countries, and Uganda is no exception to this. Decisive policies to promote household and firm survival alongside longer-term planning for growth will be crucial to Uganda’s recovery.

Early this year, the Government of Uganda took decisive action to limit the spread of COVID-19, aware of the potential disastrous effects of this disease in a country with only 55 functional ICU beds for a population of over 42 million. After putting in place a 14-day quarantine for those traveling from ‘high risk’ countries, strict nation-wide lockdown measures were put in place between March and May, limiting all non-essential business activities and public gatherings in the country. In addition, personal motorised travel was banned, a national curfew was put in place, and airports were closed for all travel.

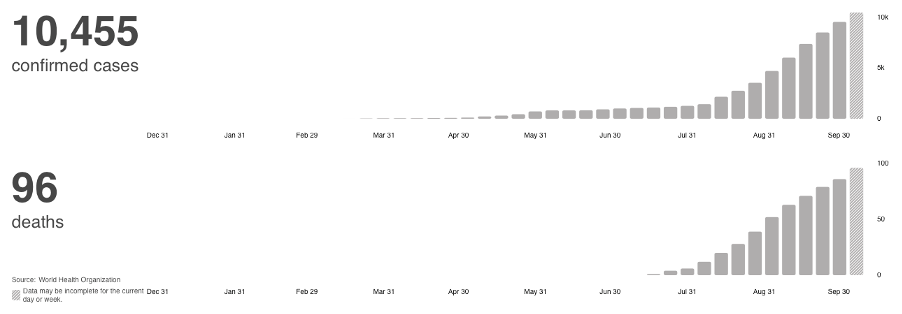

Despite worrying predictions of the potential impact of the disease on countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the health impact of COVID-19 in Uganda has, to date, been relatively limited. While the number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 have grown steadily since March (and have increased particularly since the relaxing of lockdown measures in June), we have not yet seen the exponential growth in mortality rates experienced in other countries. Infections per million of the population are currently at 229, compared to over 24,000 in the USA and 10,000 in the UK.

To some extent, the numbers may not reflect the true extent of transmission, with resource limitations preventing ongoing wide-scale testing. Daily positivity rates as a share of tests performed have been increasing in recent weeks, at around 5-7% at the time of writing. However, fatalities still remain low, especially when compared to other diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS. The relative resilience of Uganda’s population to COVID-19 is likely due in part to both swift government policies informed by past pandemics to strictly impose social distancing measures, and a notably young population – almost 50% of the population was less than 14 years old in 2014.

An economic crisis

Though the country has so far been shielded from the worst in terms of health impact, the sharp global downturn in economic activity and containment measures put in place as a result of COVID-19 have come at an enormous cost to the economy. Severe limitations on international transport have reduced exports and tourism and have further restricted access to key industrial inputs. At the same time, the collapse in the world economy has lowered remittances from Ugandans living abroad. Lockdown measures have compounded economic difficulties by preventing people from working, constituting another supply shock and a strain on people’s livelihoods. Recent estimates suggest that as a result of the global crisis and lockdown measures, 3.3 million people fell into poverty and 9.1% of monthly GDP was lost during the lockdown.

As a result, economic growth is estimated to have fallen drastically to 3.1% in 2019-20. A survey conducted by EPRC in April 2020 highlights that small businesses have been hit particularly hard, with close to 600,000 jobs lost temporarily, of which more than 80% of job losses were in the service sector. While there has been some recovery in economic activity since June, this has not been met with a commensurate increase in employment. At the same time, government revenues have dramatically fallen at a time when additional support has become most important.

Short-term policy priorities

Effectively responding to the current crisis will require a combination of short-term policies to mitigate the effects of the crisis on those hardest hit, and effective planning for medium-term recovery.

In the short run, there is an urgent need to provide assistance to households that have fallen into poverty and firms whose survival is at risk. In addition to necessary investments in improving both the quantity and quality of healthcare across the board, cash transfers to households and expansion of credit to firms is likely to play a crucial role in recovery. In a context of limited fiscal space, providing immediate assistance may require innovative thinking to improve household welfare. A recent study by the IGC, for example, highlights the potential for reducing tariffs on staple agricultural goods in raising average household incomes by 1.3%.

Planning for recovery

Alongside short-term measures, it is critical that policy remains forward-looking in planning for longer-term growth. Four priority areas for policy are clear:

- Supporting the recovery of the tourism sector, both through targeted measures to build and promote Uganda as a tourist destination, and targeted investments in necessary infrastructure and skills.

- Encouraging competitive production of tradeable goods, not through restrictions on imports that often form essential inputs for firms in Uganda, but instead through lower trade costs and targeted programmes to raise the competitiveness of domestic firms (for example, through supplier development programmes).

- Investment in the agricultural sector to ensure that it remains relatively resilient to the effects of the crisis. Investments in raising the quality and supply of coffee, for example, are likely to be particularly important in maintaining longer-term growth in exports.

- Efforts to rationalise and reform government spending in sectors such as healthcare and public service to deliver greater value for money in public investment.

There is undoubtedly a long road ahead in recovering from the current crisis. However, there are already reassuring signs of recuperation, with an early recovery in export performance since April 2020. As the country begins to open its borders, one can be optimistic that an effective balance of immediate support and longer-term reform will set Uganda on the path to recovery.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.