Road to legitimacy: Takeaways from the Fragility Commission’s 2nd evidence session

The road to reforming and rebuilding the legitimacy of a state and its institutions is long and difficult. Elections, even when free and fair, are only a piece of the foundation upon which a state must re-establish trust with citizens and can start to rebuild public services, infrastructure, and its economy.

“People don’t need ideas, they need bread.” This statement from Former South African Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan summed up the central issue debated at the second evidence session of the LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development, held at Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government on 8 June 2017.

Moderated by the Commission Chair and Former UK Prime Minister David Cameron, the session on state legitimacy highlighted the tension between ‘process legitimacy’ and ‘performance legitimacy’, that is, what makes a state legitimate – its processes and institutions or its ability to deliver to its citizens?

The commission called on four witnesses, experts with diverse backgrounds in international organisations, government, academia, and first-hand experience of political transitions, to weigh in on this issue. This blog summarises some of the session’s key takeaways.

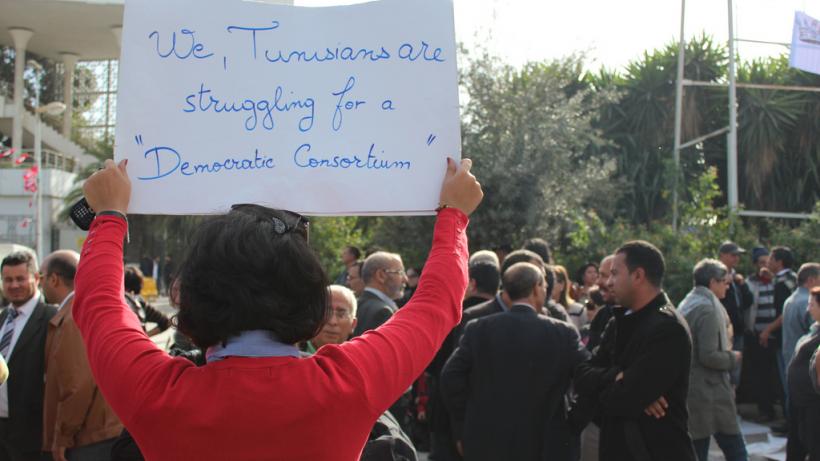

The Fragility Commission discusses building legitimate government during its second evidence session.

Elections are not enough

The witnesses agreed that the international community’s emphasis on democratic elections to grant legitimacy to a government is misplaced. Especially in fragile situations, building legitimacy requires states to address much more pressing issues such as establishing physical security for citizens, delivering basic services, and generating job opportunities.

Hedi Larbi, former Minister of Economic Infrastructure and Economic Advisor to the Prime Minister of Tunisia, pointed to the seemingly ‘legitimate’ transition in Tunisia as an example. In 2011, following a popular revolution that unleashed the Arab Spring, democratic elections were held on time and according to an agreed roadmap, but the legitimacy gained from the democratic process quickly disintegrated. The elected representatives did not deliver what they promised in terms of addressing the population’s economic and social grievances.

Source: Flickr | Amine Ghrabi

Mr Larbi argued that trust between institutions and the people is fundamental, and building that trust should be prioritised over all else. You cannot have trust without delivering services to the people, and you cannot have legitimacy without trust.

During his time in the Tunisian transition government in 2014-15, Mr Larbi said they focused on two priorities in order to build trust: 1) building the institutional capacity to deliver as many public services to Tunisians as they were capable of and 2) communicating to the people about what the government was delivering.

The risk of ‘best practice’

The witnesses also highlighted the danger of international ‘best practice’, a buzzword often used by the global community when advocating for policy solutions and processes that are widely accepted as effective across different contexts.

Keith Biddle, the former inspector general of police for Sierra Leone, said from his experiences in South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Somalia that adopting international best practices can often be a curse rather than a blessing. He pointed to success of community-based policing in South Africa and Sierra Leone. The governments requested help and expertise from abroad, but used that advice to develop their own model for community policing, led by the feedback they received from local communities. In contrast, Mr Biddle pointed to the Democratic Republic of Congo which failed to develop a coherent policing strategy, because its government was being led in too many different directions by too many international actors.

Mr Biddle also pointed out that international best practice can often be murky. For example, community-based policing could be considered a best practice for achieving security, but the practice is defined in a multitude of ways, and advice will be entirely influenced by the organisation giving it.

What to prioritise?

In fragile and conflict situations, where government capacity is extremely limited, sequencing is a key consideration – what challenge should you tackle first? The witnesses agreed that while policy priorities are very much dependent on the circumstances, providing stability and security is often the first step.

For South Africans during the transition from the apartheid system to majority rule in 1994, an interim solution in the form of a constitution to set up for a democratic election was one of the first steps, said Mr Gordhan.

In fragile states, however, a constitution does not usually fulfil the role of contributing legitimacy, said Christina Murray, professor of human rights and constitutional law at the University of Cape Town. Building a framework for governance must be accompanied by providing security, addressing corruption, and providing basic services such as access to water, healthcare, and education.

While it is clear that constitutional arrangements are necessary for legitimacy, said Professor Murray, bad constitution making can lead to long-term, negative effects on the country’s development. A constitutional process, therefore, must be preceded by having the right elements in place to make it a successful process – for example, political agreements between opposing (and sometimes warring) groups and ensuring new or existing institutions are embraced by all actors.

To build up legitimacy, reasonable compliance with the government must also be developed, said Paul Collier, academic director of the commission and director of the International Growth Centre. Citizens need to be willing to pay taxes and obey basic laws that provide security. In fragile situations, an extended period of modest legitimacy that disciplines the government to maintain constant trust with its citizens, rather than jumping into elections and making a constitution, could be much more beneficial for legitimacy in the long run, he argued.

Next steps

Mr Cameron closed the session by summarising the difficult questions regarding legitimacy that the commission will address in its final report – among them, the tension between process and performance legitimacy and the sequencing issue. Additionally, it was clear that the academic evidence on state legitimacy needs to be considered alongside the realities faced by countries in fragile and conflict situations and past experience.

State legitimacy is one of five key dimensions of fragility that the commission is examining as part of its work to form policy recommendations for national and international actors to better support economic growth in countries facing fragility and conflict. The third evidence session will take place in July 2017.