Who are the ultra-poor and how can development policy address their particular needs? In today's blog, Professor Robin Burgess discusses the results of a research project with the Bangladesh-based development NGO BRAC.

The World Bank defines the poor as those who live on less than $1.90 (USD) day, but millions of people in the developing world survive on even less. Trapped in low-skilled, insecure, seasonal work, they live extremely precarious economic lives. With low assets and few skills, their labour is often their only resource. They are the ultra-poor.

I first became interested in this group while working on research on famines in British India where I found that agricultural labourers were heavily represented in the death tolls. Subsequent research on post-Independence India found that extreme weather patterns (very hot days) are associated with increased death rates in rural India. Although famines are a thing of the past in India, extreme weather damages crops, such as rice, affecting the size of the harvest and hence the employment prospects of agricultural workers. This can be disastrous for poor agricultural workers who often depend on these daily wages for survival. Therefore when, in 2006, I came across a BRAC programme trying to change the occupations of this ultra-poor group in Bangladesh, it was something of a eureka moment. I felt that here was an opportunity to do something for a group of workers (casual labourers) who had been stuck in poverty for generations.

Labourer in Naogaon District, Bangladesh © BRAC

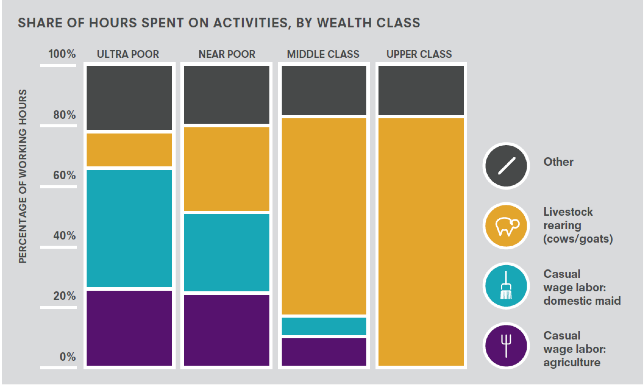

What also attracted me to this work is that this is a poverty trap for many. Casual labour is often the dominant form of employment in rural areas. Without the skills necessary to engage in more productive jobs, or the opportunities to save or borrow, to finance the purchase of productive assets or acquire human capital, the ultra-poor choose from a limited number of low paying and irregular jobs – most commonly agricultural wage labour or domestic service. In contrast, wealthier households in the same communities tend to be better insulated from seasonality and income shocks.

As depicted below, within poor villages in Bangladesh, wealthier households spend more time than the ultra-poor in more productive and stable self-employment typically rearing livestock. What is even more striking is that upper and middle class women in these villages work for more days of the year than the ultra-poor because the types of employment the ultra-poor are involved in only demand their labour at certain times of the year.

The BRAC model: Targeting the ultra-poor

Several previous studies that have tried to increase the productivity and incomes of the poor by improving their access to capital or skills, have had disappointing results. In contrast, the Bangladesh-based development NGO, BRAC developed a programme targeted at the ultra-poor that used a ‘big-push’ approach, combing both a large-scale asset transfer and skills training. The programme has helped some of the poorest women to expand their hours of self-employment work in livestock rearing.

Without the skills necessary to engage in more productive jobs, or the opportunities to save or borrow, to finance the purchase of productive assets or acquire human capital, the ultra-poor choose from a limited number of low paying and irregular jobs – most commonly agricultural wage labour or domestic service.

Women in the programme are offered a range of productive assets, such as livestock, or assets for cultivating vegetables and making and selling handicrafts. The overwhelming majority – 97 per cent – choose livestock, with a cow or cow-goat combination, possibly because they see wealthier women in their villages rearing these animals.

The livestock received by each participant was valued at approximately $140 (USD)[1], nearly double the average baseline wealth of households eligible for the programme. A training programme of equivalent value was also provided over two years to support recipients in working with their new assets. Limited savings and access to credit mean that most ultra-poor households cannot afford such assets on their own.

BRAC staff talking with CFPR-TUP member in a meeting in Sampur slum, Sutrapur, Dhaka.[/caption]

BRAC staff talking with CFPR-TUP member in a meeting in Sampur slum, Sutrapur, Dhaka.[/caption]

How the programme works

Once a village was selected, BRAC conducted a household census documenting the household’s head, size, and occupations. Household wealth data was derived from a participatory wealth valuing organised by BRAC in each village. The women from the poorest households are offered the opportunity to take part in the programme.

Our research team worked with BRAC to develop a randomised control trial, a simple but rigorous test to assess whether the ultra-poor programme is effective at transforming the economic lives of these women. We evaluated 1309 communities in 13 of Bangladesh’s most vulnerable districts.

We surveyed households two, four, and seven years after the programme’s implementation. The study tracked all poor households, both eligible and ineligible for the programme, for comparison.

Unlike evaluations of similar programmes, our study tracked an additional 10 per cent random sample of households from other wealth classes. This was used to assess the effect of the transfers on other wealth classes in the village and to rule out the possibility that gains to ultra-poor households came at the expensive of non-eligible households.

Key results

One of the key things I was interested in, particularly for women who had been associated with the programme for four years, was whether they had diversified into other businesses. It turned out, a large number had.

Strikingly, although programme households were permitted to liquidate the assets after the programme ended, the vast majority not only retained their initially transferred livestock but many even purchased additional livestock.

Access to livestock enables ultra-poor women to spend more time in self-employment. Four years on, the women worked 25% more days in the year and increased their average earnings by 37%.

Results persist seven years after the start of their programme, and five years after programme support ends. The fact that having access to self-employment seems to drive poverty alleviation in this study suggests that the ultra-poor are not poor because they are unwilling, or unfit to work similar jobs as their wealthier neighbours. Instead, a core research finding was that the ultra-poor face a myriad of barriers, many stemming from their initially low levels of wealth and human capital, that prevent them from independently accessing the capital and skills they need to work in the same occupations as wealthier women. Engaging in more productive self-employment also enables the ultra-poor to better smooth their labour supply throughout the year so that they work more regularly throughout the year than they were at baseline. This reduces the negative impacts of income shocks from irregular or seasonal work.

Due to the programme the share of the households living below the extreme poverty line is reduced by 8 percentage points after four years. Data on consumption, expenditure and savings of ineligible households support the conclusion that gains to ultra-poor do not come at the expense of other households.

the ultra-poor face a myriad of barriers, many stemming from their initially low levels of wealth and human capital, that prevent them from independently accessing the capital and skills they need to work in the same occupations as wealthier women

As is illustrated below, pilot programmes based on BRAC’s model have been adapted and tested in six other countries, with highly promising results. Positive impacts on the earnings and welfare of ultra-poor households suggest that the programme can be scaled up and replicated in other contexts and by other implementing organisations. The programme is also rapidly attracting the attention of governments. If it can be integrated into the social protection programmes of governments across the developing world, this programme has the potential to contribute to achieving the first Sustainable Development Goal target – eradicating extreme poverty by 2030.

Further research is still needed for us to determine exactly which programme components were the most effective at reducing poverty and how different components affected different participant groups. Overall, the success of the programme suggests that approaches that combined asset and skills transfers have the potential to transform the economic lives of the millions that currently live in extreme poverty.

[1] All monetary values are reported in 2007 USD.