The challenge of water provision in rural Tanzania

Despite significant recent investment, levels of access to clean drinking water in Tanzania remain similar to those of 20 years ago. Why is it that although money has been flowing, water continues to trickle?

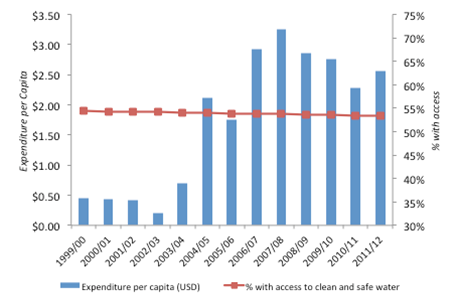

The Tanzanian NGO Twaweza recently released a research brief detailing the ongoing challenge of access to clean water in the country. The brief showed that just over half of all Tanzanians (54%) obtain their drinking water from an ‘improved’ source; the figure for rural citizens is even lower at just 42%. These findings become even more striking when put in the context of recent investments. As shown in the figure below, Tanzania’s current level of access is similar to that of 20 years ago, despite a lot of money having been spent.

Sources of data: Tanzania Public Expenditure Review (PER) of the Water Sector, 2009; Tanzania PER 2010; 2013 Overseas Development Institute Rapid Budget Analysis of the Water Sector in Tanzania; National Accounts of Tanzania Mainland 2011; World Bank World Development Indicators; World Bank/IMF Consumer Price changes data.

So why is it that although money has been flowing, water continues to trickle? There are several reasons. The first has to do with priorities. Prior to the Water Sector Development Programme (WSDP) – a sector-wide approach launched in 2006 – the vast majority of investments in the water sector were directed to urban areas (where only one quarter of all Tanzanians reside).

Furthermore, a recent WSDP evaluation carried out by Oxford Policy Management (OPM) suggests that while more money is being directed toward rural water supply, it is not being spent efficiently. The OPM evaluation found the average cost per rural water point beneficiary to be roughly 59USD - substantially higher than the planned cost of 36USD, as well as considerably higher than DFID’s cost per capita for rural water programmes in the region, which range from 22USD to 36USD.

The OPM report does not try to account for what seems to be driving the apparent lack of value for money. In this blog we draw from our recent work in Tanzania to suggest some answers.

The WSDP to date has been characterised by closer observers of the water sector as highly flawed. The biggest single problem appears to be implementation of the “10-village schemes”, through which local government authorities were supposed to select the 10 neediest villages within their jurisdiction to receive new, WSDP-funded projects. Design and construction of the projects was contracted out to private consultants who were to visit the villages selected and consult with community members in order to come up with suitable designs. Through a combination of poor coordination and procurement bottlenecks, the design process proved to be extremely time-consuming and expensive. But the main driver of cost inflation was the designs chosen: communities chose (or were encouraged to choose) much costlier technologies than anticipated. It was in the consultants' interest to design more expensive projects, which would ultimately increase their cut of the funding. As a result, in most districts only two or three WSDP projects have been implemented to date, out of the 10 originally planned.

Beyond the problems with the design stage, one of the key culprits for weak implementation of WSDP to date is thought to be the widespread lack of accountability or performance management that characterises the water sector. One long-serving consultant to the water sector (who has since left after years of frustration) described his experience trying to build a financial management system for the WSDP. The exercise proved to be nearly impossible, as no one in the Ministry had ever compiled a list of contracts signed, recorded how much was spent against each one, and how that reflected the budget. Compiling this information took four months and, despite being incomplete, revealed a “staggering amount of wastage.”

Similarly, there is very little monitoring of funds from the central government down to the district level. The lack of monitoring relates to a challenge of coordination of the over 300 government agencies involved in implementing the WSDP. In particular, there is a lack of clarity regarding the responsibilities of the Prime Minister's Office - Rural Administration and Local Government (PMO-RALG), which has traditionally been the main oversight body governing district authorities, and the Ministry of Water (MoW), which leads the WSDP and sends WSDP funds down to the district level.

A lack of information is not the main culprit, however. As one World Bank employee noted, “the Ministry knows everything that goes wrong, but that doesn't lead to action. They need something more than just information.”

The question then becomes: what would lead to action? There is a clear need for better incentives - for both the Government of Tanzania (GoT) and donors who fund the water sector - to ensure that money spent in the water sector is not wasted. Two recent initiatives on the horizon offer some hope.

First, the government has included rural water provision among the six priority sectors that are part of Big Results Now (BRN). BRN was launched with great fanfare in February 2013 and represents an attempt to duplicate a similar development initiative from Malaysia. After selecting six priority sectors the GoT convened intense eight-week, heavily focused problem-solving ‘labs,’ which were to produce concrete action plans with clear milestones and targets. The goals and targets that emerged from the lab for the water sector are very ambitious: According to the Minister for Water, the three-year initiative would result in access for more than 15.4 million people living in rural areas, raising the percentage of people with access to clean water to 75 percent by 2015.

Despite being seen as politically motivated (BRN targets align neatly with the 2015 election), many working in the water sector see BRN as bringing much-needed momentum and attention the long neglected rural water sector. Most importantly for this discussion, BRN includes performance management as a key ‘enabler’ for delivering results. While the details of the performance management enabler are still sketchy, some proposals have included a ranking system for local governments that will publicise officials’ achievement (or failure to achieve) targets, and then be used as a key criteria in determining the budget allocation to local governments. BRN also includes Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that higher-level officials are supposed to achieve within specific timeframes.

Of course, if the government is left to monitor itself, the problem of poor incentives still looms. This is where the second recent initiative comes in.

Late last year, the Ministry of Water released a comprehensive water point mapping database, with information on all 74,289 public improved ‘water points’ (communal standpipes, hand pumps, improved springs, dams and cattle troughs) serving rural communities in mainland Tanzania. The release of the WPM data has already forced the Ministry to concede that coverage in rural areas was much lower than they had been saying (34% rather than 64%).

If the water point mapping data is used to see if the BRN targets are achieved, and well-publicised to people who can make a difference (the donors who fund the water sector and the citizens whose votes ruling party politicians rely on), perhaps there is more than a trickle of hope for things to improve in Tanzania’s water sector.