Despite reducing gender inequalities over the past two decades, COVID-19 threatens to erode Mozambique’s gains as the pandemic’s social and economic consequences disproportionately impact women and girls. To prevent backsliding and continue progress towards gender equality, Mozambique needs greater investments in access to basic services, enhanced social protection systems, and greater gender sensitisation of pandemic response policies.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our International Women’s Day series.

The COVID-19 pandemic has produced severe socioeconomic implications, deepening pre-existing inequalities and exposing vulnerabilities across social, political, and economic systems – which in turn amplify the impacts of the pandemic. In this context, this blog seeks to analyse the gendered impacts of COVID-19 in Mozambique by describing the country’s gender profile; reviewing the gendered dimensions of poverty, employment, and education; and identifying the main challenges and ways forward to improve gender equality in the post-COVID-19 era.

Gender profile in Mozambique

Since its independence in 1975, Mozambique has made strategic efforts to eradicate the barriers that limit Mozambicans' socioeconomic development, seeking to include men and women equally in the development process. According to the United Nations, in the age of the SDGs “gender equality is not just a fundamental human right, but the necessary basis for building a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world”. Without equitable development of half of the world’s population, achieving the SDG goals and targets will not be possible.

Along this path, Mozambique pledged to adopt national mechanisms and strategies, as well as regional and international agreements, to reduce gender inequalities. In this effort the government has initiated the Gender Policy and the Strategy for its Implementation, the National Plan for the Prevention and Combat of Gender-Based Violence (2018-2021), and the approval of the Health Sector Gender Inclusion Strategy (2018-2023).

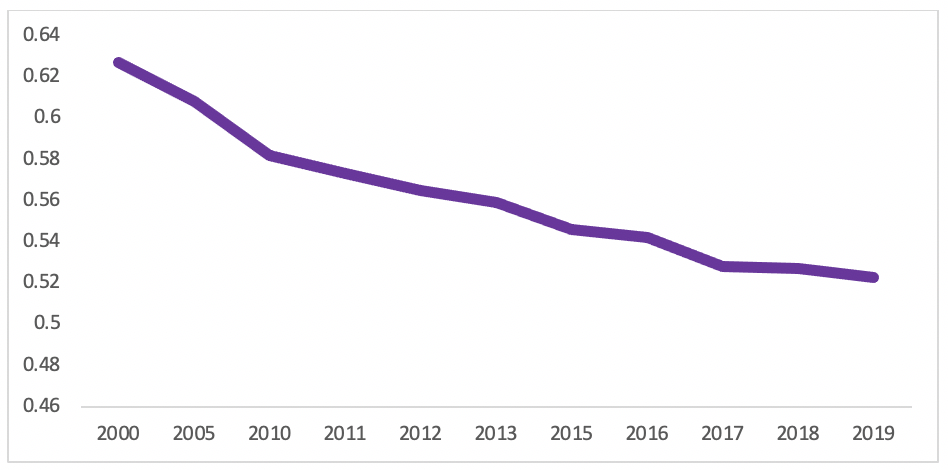

These mechanisms along with past efforts have made it possible to realise significant progress in combating gender inequality, as shown in Figure 1 on the country’s performance on the UN’s Gender Inequality Index.

Figure 1: Gender Inequality Index, Mozambique Source: UNDP- Human Development Report, 2019

Source: UNDP- Human Development Report, 2019

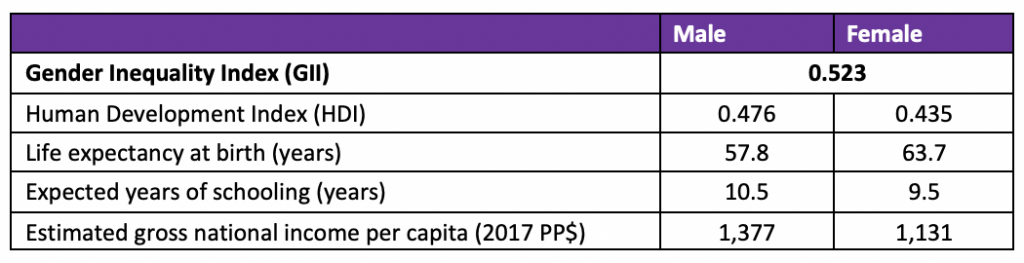

Despite significant progress, however, gender equality still requires continued effort, as seen in Table 1. While women’s life expectancy at birth surpasses men’s, their educational outcomes and incomes still fall short. These disadvantages can worsen in the context of COVID-19 and undermine past achievements as the pandemic has shown to have a greater impact on vulnerable populations, such as women, children, and informal workers.

Table 1: Gender Inequality Index in Mozambique Source: UNDP- Human Development Report, 2020

Source: UNDP- Human Development Report, 2020

Gendered impacts of COVID-19 on poverty, employment, and education in Mozambique

Around 46% of people in Mozambique live below the poverty line, according to the 2014-15 Family Budget Survey (IOF). The IOF report states that poverty is higher in rural areas (53.1%) and relatively lower in urban areas (40.7%). Poverty affects more women than men, with 63% of female-headed households being poor and exposed to food insecurity, compared to 52% of male-headed households. These statistics support the implication that as the effects of COVID-19 disproportionately impact poor and vulnerable households, women face a greater burden. Looking to gender gaps in educational outcomes, 57.8% of women are illiterate, compared to 30.1% of men, placing women in a greater situation of vulnerability to secure stable employment and break the cycle of poverty.

According to a recent report by OMR conducting micro-simulations based on the consumption poverty criterion, poverty is projected to significantly increase in Mozambique following the pandemic. At the national level, poverty rates may increase from 46.1% (IOF 2014-15) to 77.7%. Using the US$ 1.90 international poverty line, that share rises to 93.1% due to the impacts of COVID-19.

In the second quarter of 2020, employment decreased by 29.3% and 75.9% compared to the previous and homologous periods, respectively, according to the analysis of the labour market. Women disproportionately work in informal labour activities, without any form of insurance or formal social security. In Mozambique, around 92.3% of the informal employment outside of agriculture is done by women, predominantly with low education. Female agricultural workers also have lower technological adoption rates and more limited access to credit compared to male agricultural workers. Labour market disruptions, including movement restrictions imposed by COVID-19, therefore, further disadvantage women’s ability to make a living and meet their families’ basic needs.

The restrictive measures imposed to contain the spread of COVID-19 had a severe impact on education. In March 2020, the Government announced the closure of all public and private schools (including kindergartens and universities) for 30 days from 23 March 2020, suspending education to around 8.5 million students in close to 15,000 schools. With the interruption of face-to-face classes in some grades and complete paralysis in others, mainly without exams, the risks of backsliding on past achievements to keep girls in school and combat premature marriages became more pronounced. These risks in the long term may cause further distortions in the labour market and threaten the quality of women’s employment.

Challenges and way forward

Understanding the gender-differentiated impacts of the COVID-19 crisis through sex-disaggregated data is fundamental to designing policy responses that reduce vulnerabilities and strengthen women's agency. This is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities but also about building a more just and resilient future. Therefore, Mozambique should continue its efforts to increase women’s access to basic services like education, health, sanitation, and electricity, as well as access to labour markets and means of production. Specifically, the county should:

- Continue to develop sex-disaggregated statistical surveys that allow for the design of gender-sensitive policies with localised interventions.

- Strengthen the capacity to implement and interpret instruments on equal rights between women and men.

- Rethink and revise the education curriculum to the current context in order to increase the access to and quality of education.

- Maintain the health and nutritional needs of the population, with a special focus on vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women and young children.

- Within the scope of national social protection programs, prioritise vulnerable groups such as women, children, and female-headed households, particularly in rural areas, in support of access to basic services. Furthermore, the ‘I want to be formal’ campaign should be intensified in the informal sector to support economic activities such as microfinance, banking, and microinsurance.

- Rethink and reflect on the current social security system to more effectively respond to the needs of pensioners in times of crisis such as that imposed by the pandemic.

- Intensify professional training programs in rural areas with a focus on agriculture (the sector employing a majority of women), including best practices and promotion of cash crops.