Transforming secondary cities in Uganda for job creation

Across developing countries, the combined forces of rapid population growth, a burgeoning youth workforce, and urbanisation have created a policy imperative to generate jobs at an enormous scale. While primary cities must play a role in this job creation, it is unrealistic to imagine that all the necessary jobs, or even the majority, can be created in a single metropolitan area. Governments must focus on creating jobs and promoting economic development in secondary cities.

Developing secondary cities in Uganda

Uganda is one of the countries where this development challenge is most apparent. From 2002 to 2014, the size of the labour force increased by six million – far exceeding the 500,000 new wage jobs created in Kampala, the capital city, during the same time period. In recognition of this challenge, Uganda is taking steps to strengthen secondary city economies.

In a recent study, JustJobs Network studied the characteristics of labour markets in urban settlements across the country to identify viable job creation strategies. Findings indicate that structural transformation and the growth of non-farm employment opportunities are proceeding slowly in the secondary cities of Uganda — with the capital city of Kampala currently dominating the country’s economic and urban system. Uganda must reconsider existing policies to stimulate growth and job creation in cities beyond Kampala in order to achieve inclusive development and realise the potential of a young workforce.

Kampala is growing swiftly but labour market prospects are dimming

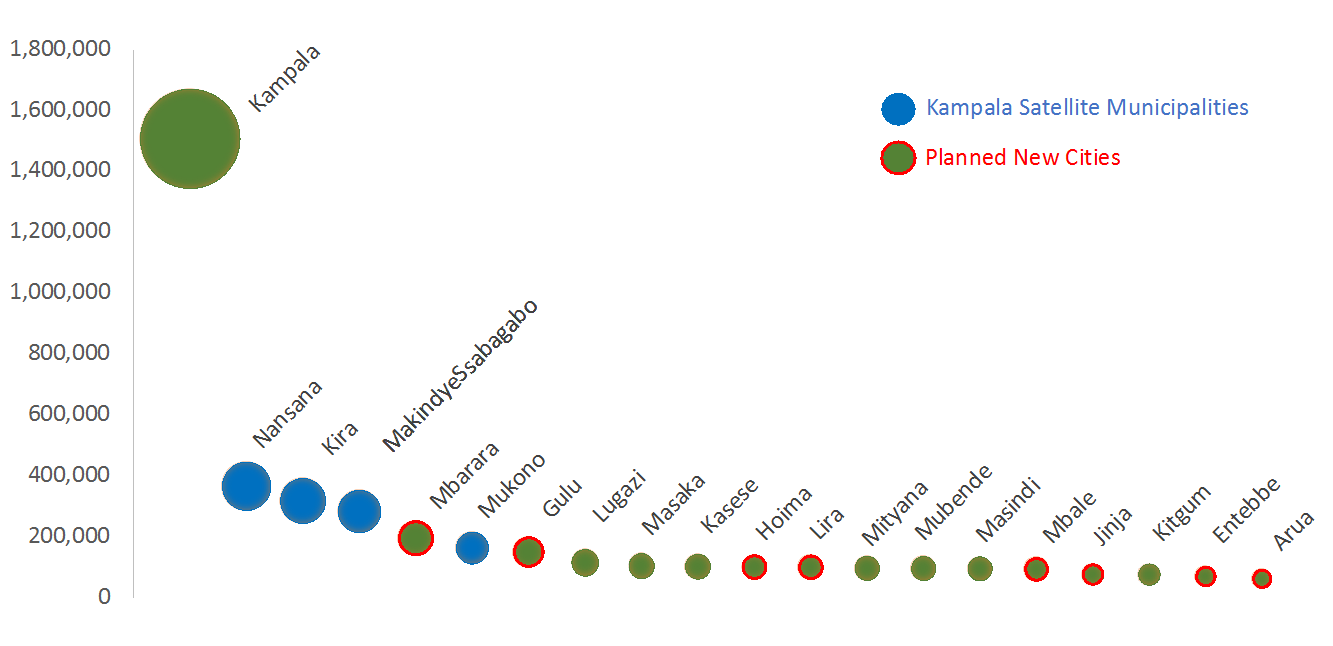

Uganda has one of the highest population growth rates in the world at 3% per year. The capital city of Kampala dominates the country’s urban system, with over 4.3 million inhabitants in the metropolitan area. Beyond Kampala and its satellite municipalities, Uganda has a very flat urban hierarchy, with no cities above 200,000 inhabitants (Figure 1).

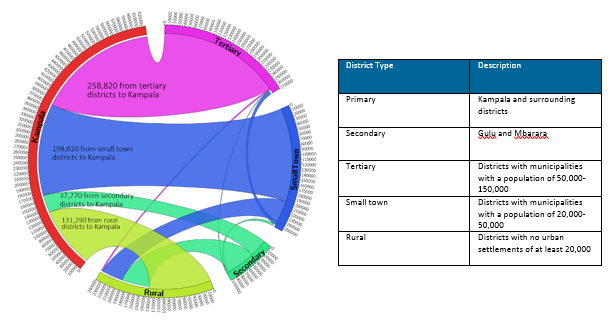

About 38% of the population growth in the capital city region is due to migration from other parts of the country, including smaller urban settlements. Due to out-migration (Figure 2), population growth in secondary and tertiary cities lags far behind Kampala, with these urban settlements growing more slowly than small towns and more rural settlements.

Figure 1: Population of urban settlements in Uganda, 2014

Source: National population and housing census 2014

Source: National population and housing census 2014

However, as the city continues to grow rapidly with migration from other parts of the country, a declining real wage (wages fell by 5% during 2013—2016) and increasing unemployment demonstrate that its labour market may be growing saturated.

Figure 2: Net migration flows across district types, 2002-2014

Source: National population and housing census, 2014.

Source: National population and housing census, 2014.

Note: Net migration flows are calculated by taking the number of people that have migrated from one typology to another and deducting the number that have migrated in the opposite direction.

Secondary cities lag far behind

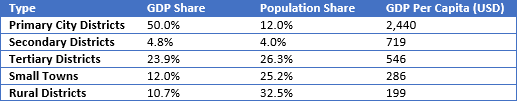

Even as Kampala’s economy shows signs of weakening, higher-value economic activity remains highly concentrated in the capital, as evidenced by gross domestic product (GDP) shares by district (Table 1). Compared to other cities, Kampala has higher wages (real wages are 50% higher than in any other city), a diversified economy, and more non-farm job opportunities and wage employment per capita.

Table 1: GDP, GDP per capita, and population shares across district types, 2014

Source: National population and housing census data, 2014.

Source: National population and housing census data, 2014.

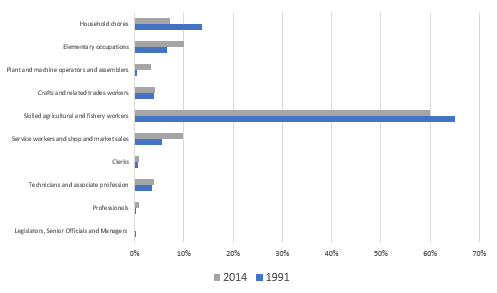

The out-migration observed in smaller urban settlements can be attributed to a lack of economic opportunities. Structural transformation in secondary and tertiary cities is proceeding slowly, and productive non-farm employment opportunities remain limited (Figure 3).

Moreover, outside Kampala, wage employment is limited. In 2014, most workers (at least 75%) in smaller urban settlements remain in more vulnerable forms of employment, such as self-employment or unpaid labour.

Figure 3: Secondary city district workers by occupation category, 1991-2014

Source: National population and housing census, 1991, 2014.

Source: National population and housing census, 1991, 2014.

Note: Figures represent the percentage share of total workers in secondary city districts.

Some bright spots, however, signal the potential of secondary urban centres. First, wage jobs are increasingly being created outside of Kampala. Second, the educational attainment of workers in secondary cities has grown since 2002. Third, rural households are diversifying into higher value-added crops and there is growth of non-agricultural household enterprises. Greater focus on job creation and economic development in these geographies can accelerate the momentum.

Job creation initiatives translate poorly at the local level

The existing institutional architecture for job creation in Uganda initiatives is characterised by fragmentation. The most relevant and effective job creation initiatives are controlled by the central government, with local governments having limited ability to adapt these programmes to local needs and locational advantages.

Moreover, current efforts by the central government to support job creation focus on promoting self-employment through entrepreneurship as opposed to more vigorous support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are positioned to grow and become job creators.

An initiative to establish industrial parks across the country to encourage foreign investment has so far created few new jobs outside of the capital and may even exacerbate regional inequalities. And without deliberate government policies to support linkages to local firms, industrial parks are unlikely to have a sustainable impact on job creation.

What policies can jumpstart growth of secondary cities?

As more young people join the working-age population and those in proximity of smaller urban settlements look for non-farm work opportunities, secondary cities can play an increasingly important role as centres of economic opportunity. Leveraging their potential requires more deliberate policy aimed at transforming smaller cities from market and service centres into productive hubs of job creation.

To transform secondary cities for job creation, there is a need to:

- Support the growth of SMEs through a systematic value chain approach to vocational training and bolstering initiatives to promote local content.

- Revise the approach to industrial parks to strengthen linkages to local supply chains.

- Adopt place-sensitive policies that — unlike the industrial parks programme —leverage existing infrastructure and business clusters while encouraging investment in a larger area, such as a city or district, and targeting sectors that are strategic for secondary city growth.

- Strengthen local government capacities to promote local economic development by reinvigorating the push for decentralisation and promoting increased policy autonomy and funding for local governments.

These strategies should be adapted to the locational advantages of specific settlements. For several secondary cities, these opportunities could be found in tourism and food system value chains.