West Africa’s artisanal gold mining sector: An overlooked driver of development?

Most recent research on mining sector policy reform in West Africa has focused on the potential of large-scale multinational mining companies to transform developing economies. There has been comparatively less analysis of the economic impact of mining activities carried out informally and at a micro-scale.

The artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector – informal, low tech, labour intensive extraction and processing, which is carried out predominantly by local people – has, for many years, been overlooked by African policy makers as an important alternative livelihood and driver of rural development. Yet, in the four Mano River Union countries – Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Cote d’Ivoire – artisanal gold mining occupies a central position in the rural economy, with hundreds of thousands of poor people depending on it to make ends meet.

The study: Livelihoods of artisanal gold miners in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Focusing on Sierra Leone and Liberia, the locations of two of West Africa’s most buoyant and dynamic artisanal mining sectors, we undertook an 18-month study to better understand how individuals engaged in artisanal gold mining manage their finances and draw upon their social networks to negotiate the informal structures of the sector.

Over an 11-month period, we monitored 73 artisanal gold miners and their financial supporters, all of whom were living and working in close proximity to the border between Sierra Leone and Liberia. Employing an innovative methodology involving the compilation of the ‘financial diaries’ of those engaged in the sector, the findings confirm that gold is an important mechanism of trans-border exchange.

Key findings: Untapped potential

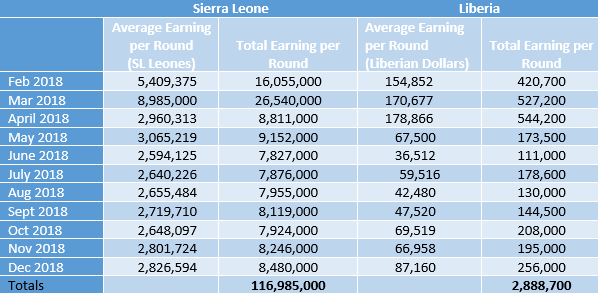

- Despite being associated with a host of environmental, health and safety, and social concerns, the artisanal gold mining sector in Sierra Leone and Liberia provides essential livelihood support to hundreds of thousands poor people, supplying valuable start-up capital for other economic activities (Figure 1). The highest levels of income from gold mining tended to be generated during the dry season (November to May), while earning tapered off during the rainy season (June to September), when miners returned to their farms to plant their crops.

Figure 1: Income earned from gold mining across all sites in each country

Figure 1: Income earned from gold mining across all sites in each country

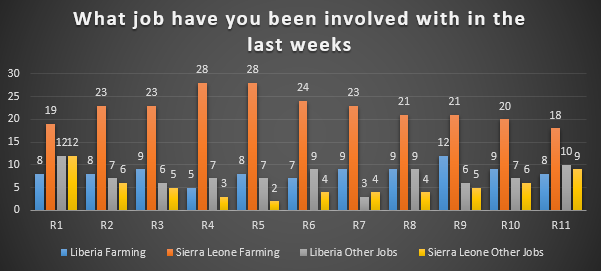

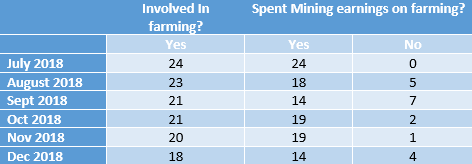

- At all of the study sites surveyed, the data revealed that respondents on both sides of the border generally managed diversified livelihood ‘portfolios’, engaging in a variety of economic activities over the duration of the year (Figure 2). In particular, mining-farming linkages were strong, with the income generated from the gold mining sector contributing significantly to the farming economy. The financial diary exercise revealed that the farming and mining economies complemented each other, with miners carrying out farming activities throughout the year, and investing a considerable amount of gold mining revenue in farm labour and inputs (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Rural livelihood activities at study sites in Sierra Leone and Liberia (Feb - Dec 2018)

Figure 2: Rural livelihood activities at study sites in Sierra Leone and Liberia (Feb - Dec 2018)

Figure 3: Mining income spent on farming in Sierra Leone (July - Dec 2018)

Figure 3: Mining income spent on farming in Sierra Leone (July - Dec 2018)

- The findings revealed that gold is an important mechanism of trans-border exchange, particularly across the Sierra Leone-Guinea border. Many respondents in Sierra Leone described how gold was used as a form of currency in Guinea. The close proximity to the border made it possible for miners and supporters to cross into Guinea and exchange gold for merchandise, which would then be brought back into Sierra Leone to sell or trade.

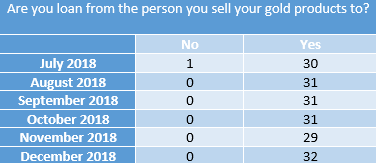

- In both Sierra Leone and Liberia, finance and lending systems remain informal and unregulated, leaving poor people susceptible to exploitation. In Sierra Leone, respondents were asked about money lending arrangements between the months of July and December 2018, and almost all respondents reported that they received loans from gold buyers, which they repaid over time in gold (Figure 4). Conditions for the loans varied, but it was clear that buyers were paying below market rates for the gold, in exchange for their loan services.

Figure 4: Are you receiving a loan from the person you sell your gold to (Sierra Leone)?

Figure 4: Are you receiving a loan from the person you sell your gold to (Sierra Leone)?

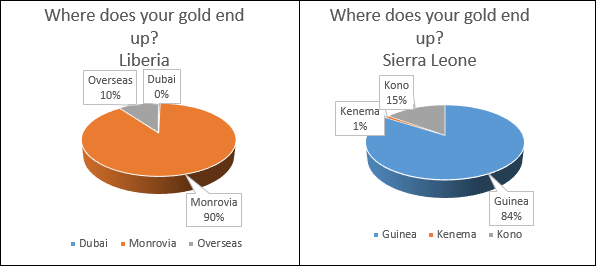

- Market mechanisms for buying gold remain poorly-developed and are dominated by informal buyers who operate outside the legal domain. Geographical remoteness from urban centres, poor road connectivity to gold buying centres, and the high cost of transportation create dependencies with informal buyers (jullas), who purchase gold from diggers at the point of extraction. In Sierra Leone, the majority of gold was ending up in Guinea due to the close proximity of sites to the border. In Liberia, it was much easier and less expensive to travel to the capital city, so most gold, it was reported, ended up in Monrovia (Figure 5).

- As artisanal gold mining is largely informal and unregulated, a sizable share of income disappears into informal channels. Consequently, governments are deprived of substantial revenue, which could be captured if effective taxation schemes were in place under a formalised system.

Figure 5: Final destination of gold in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Figure 5: Final destination of gold in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Policy recommendations: Formalisation of the sector

The formalisation of artisanal gold mining – that is, moves made specifically to bring illicit operators into the legal domain, whilst at the same time improving both working conditions and financial inclusion for diggers at the bottom of the chain – could have a transformational effect on rural livelihoods in Sierra Leone and Liberia, whilst simultaneously bolstering revenue for government, principally through taxation and export earnings.

In mapping the financial flows that take place in close proximity to border regions in Sierra Leone and Liberia, this research provides a more nuanced understanding of the socially-embedded nature of informal economic systems in gold mining areas. It demonstrates that better access to markets is an important step in reducing miners’ dependencies on informal buyers.

If more regulated buying systems were put in place, miners would likely receive a better price for their gold, and the government could generate tax revenue at the source of production. This would be a more effective way for the government to generate tax revenue, since the various export taxes between the Mano River Union countries are currently not harmonised, which creates a situation that encourages smuggling across porous and unregulated borders.

There is also an urgent need to support policies and programmes that create better financial loan systems for miners. Debt bondage and parasitic relationships with buyers prevent diggers from escaping poverty. But policies that are more fine-tuned to connect with diggers and ultimately empower them financially could improve the economic position of poor mining communities, whilst simultaneously providing a steady stream of tax to the state.

At the policymaking level, more research is ultimately required to provide the fine-grained evidence that is needed to inform policy debates on informal artisanal mining, formalisation, and income-generation, particularly evidence that centres on the gold mining sector and rural economic development.

Editor's note: A policy brief from this project can also be found here.