Why we don’t know the real number of COVID-19 deaths in Africa

The number of COVID-19 deaths is surprisingly low in Africa. Could the 'excess deaths' on the continent be hiding a different reality?

According to the African Centre for Disease Control, the total confirmed COVID-19 deaths for Africa has now reached over 41,200 – a staggeringly low number compared to the total deaths in other regions. Experts agree, however, that the number hides a very different reality. Many African countries’ official COVID-19 statistics don’t accurately reflect the true death toll due to a number of factors. This includes victims without a positive COVID-19 test being excluded from stats, lag times in the processing of death certificates, and indirect deaths from other diseases because people decide not to go to the hospital. More alarmingly, there are big data holes in countries like Tanzania, which hasn’t reported any COVID-19 cases or deaths in months.

Tracking ‘excess deaths’ – i.e., comparing the number of all deaths in a certain period with the historical average for that same period – is one way around this data accuracy problem. While media outlets like the Economist and New York Times have been tracking these ‘excess deaths’ since the start of the pandemic, data from Africa is largely missing, with South Africa typically being the only country tracked. The limited information available for African countries is creating a warped perception of COVID-19’s impact on the continent. Media outlets are already reporting that Africa has been spared the worst of the pandemic without accurate data.

The South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) is publishing weekly numbers of excess deaths but is one of the few institutions doing so on the continent. By mid-July, South Africa was seeing almost 60% more deaths than would be expected based on data from previous years – a significant contrast from the official number of COVID-19 deaths reported.

Where is the missing data?

The problem is accurate death data has always been missing – 45% of deaths globally go unregistered. This problem is even more acute in developing countries where civil registration of deaths is often less than 20% complete. According to a recent Vital Strategies and World Health Organisation (WHO) report:

“Hospitals, as the main source of cause-of-death data, are frequently not integrated into the civil registration system, and many systems are only partially digitised, leading to significant lag times in reporting. Furthermore, not all countries use the international standard form of the medical certificate of cause of death and hence are unable to apply the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) rules of mortality coding. This makes it difficult to statistically analyse cause-of-death data over time and to compare between jurisdictions—even where deaths are carefully certified.”

In Ghana, for example, each death is recorded by hand in each of the country’s 216 districts. The handwritten records then get sent to a central office in Accra and are eventually copied – again by hand – in a central death registry (see photo below). During a global pandemic, digital data on deaths is even more of an urgent need for governments to enact effective health policies, but the nature of current death records make real-time information almost impossible to access.

Source: Lagakos and Sowa, 2019

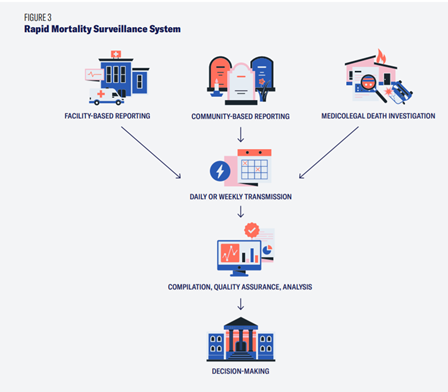

What can governments do in the face of these data challenges? Organisations like Vital Strategies and the WHO are advocating for the implementation of ‘rapid mortality surveillance’ systems, which draw from key sources to produce the data needed to analyse excess mortality on a weekly basis.

Source: Vital Strategies and WHO, 2020

In Cape Town, the city government developed a practical solution to record excess deaths by having various private and public sector bodies who are responsible for the burial and cremation of bodies report data to the city through a simple Google form and a WhatsApp group to coordinate the system among participants.

While we may never know the true death toll of COVID-19, these examples show practical steps that can be taken now to ensure policy responses are informed by real-time data.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.