Adjusting the export-for-growth model

Trade brings numerous benefits, chief among them competition, yet today’s outlook for trade remains uncertain. Is it time to re-think the primacy of exporting for growth? This third blog in a series explores the issue.

A successful development model in the last few decades has been for developing countries with low labour costs to jump on the lowest rung of the value chain, export, and subsequently work their way up. As a country’s workers get skills and expertise from dealing with international firms, the economy can jump up onto the next rung of the value chain. Economic development, a process of continuous economic and technological upgrading, is open to all those who can develop industries consistent with their comparative advantage. China has been following in the footsteps of Japan, with new suitors such as Vietnam or Bangladesh eyeing to take its place.

Slowdown in demand for consumption

All of this presumes ample trade opportunities, easy integration into value chains, and a competitive edge in low-cost production. However, with an uncertain international trade outlook, it is not obvious whether a developing country should rush to export to global markets. First, the insatiable demand for consumption is finally losing its appetite. Growth is picking up but there are questions over whether we will return to the rapid consumption seen previously (IMF, 2016). In the three decades preceding the financial crisis, the ratio of world merchandise trade growth to GDP growth was around 1.8%; in recent years this figure has hovered only slightly above 1%.[1] As China gradually reorients its economy into becoming a centre for growth with more advanced industries, new opportunities for export may sprout up for a fortunate few. However, such changes will take place over many years.

A bleak trade outlook

On top of weak demand, a globalisation backlash in Europe and the United States affects traditional export markets. A trade war started by one will spark retaliatory protectionist measures by others. Countries who initially avoid the fray might see a new influx of diverted goods come their way under a trade war, forcing them to enact their own measures to protect domestic interests. The first impact of this comes from uncertainty. A fuzzy trade outlook holds back investments and increases the risk of exporting. The door to certain markets may even be shut altogether, be it from isolationism or conflict. Once enacted, protectionist measures reduce both exporters’ cost competitiveness and domestic consumers’ demand through higher prices. The combined effect is that the expected profitability of exporting falls significantly.

In addition, some businesses may be forced to slice up value chains while others might double down on existing relations within their supply chain to ride out the storm together. Newcomers looking to enter the export market will find it even more challenging to find a prospective suitor.

Domestic trade may be more sustainable in the long run

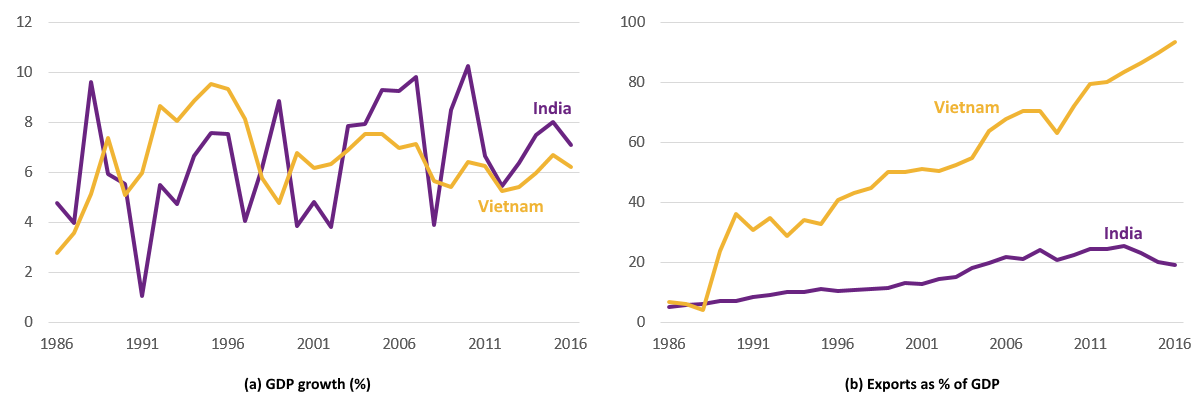

Instead, a safer model might be to look at countries which may have grown less quickly, but which have done so by relying less on the export of goods. This applies even more to economies that have already struggled to get a foothold on the export market under calmer times, such as many countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Catering to domestic demand might produce smaller headline figures but prove more sustainable in the long-term. Vietnam, for example, is a textbook case of implementing a successful export-for-growth model, but several other stars have experienced decent growth for other reasons. India and Vietnam have experienced similar levels of growth over the last three decades but their blueprints have been very different.

GDP growth and share of exports in GDP. Data: World Bank

GDP growth and share of exports in GDP. Data: World Bank

Services, not manufacturing, drew in labour from agriculture in India, resulting in a much lower share of exports in GDP. An important caveat, however, is that the services which India moved into are both tradable and routine – exposing them to similar risks that manufacturing faces from automation in the future.

Of course, India is fortunate in having a vast domestic consumer base. For other countries wrestling with poverty and unemployment, they will find it difficult to emulate India. What is clear, however, is that exporting as the panacea for rapid development may no longer hold in today’s context, especially for those who are just taking their first few steps. A balanced approach focused on building up local firm productivity while gradually interacting more in global markets may ultimately prove more successful in unorthodox times.

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of a 5-part series on unorthodox policies for unorthodox times.

[1] https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres18_e/pr820_e.htm