Breaking the clientelist trap: Creating demand for good governance in India

A perennial challenge for reformist politicians is how to sustain their governance reforms beyond their first term in office. In poor contexts, clientelist politicians can out-compete reformers by threatening to exclude those who vote against them from accessing public benefits. How can reformers in office counter these tactics, break the clientelist trap and create a demand for good governance from voters that ensures they are re-elected? This study seeks to gather evidence on how voters’ political attitudes and behaviour were affected by a sharp improvement in governance in Bihar state, India.

The study

Governance reforms in Bihar

In 2005, Nitish Kumar became Chief Minister of Bihar following the downfall of the Lalu Yadav regime. Rather than replicate the clientelist `jungle raj’ of the Lalu era, Nitish Kumar introduced extensive governance reforms, rebuilding bureaucratic capacity and improving public service delivery.

The political effect

As other International Growth Centre (IGC) studies have shown (see reference list), reforms have sought to enforce clear rules of access and to undermine opportunities for clientelism and corruption. While the economic and social effects of these policies have been studied, their political effect has not. Yet, how voters respond to these policies is crucial to understanding Kumar’s repeated re-election and the prospects for the longer-term continuation of Bihar’s governance improvements.

Existing analyses have been sceptical about the ability of policy to create its own political support, both because programmatic policy provides no selective reward to voters and therefore no incentive to vote for reform (Imai et al., 2016). Furthermore, poverty continues to make citizens acutely vulnerable to clientelist threats that might cut off their only source of income (Stokes et al., 2015).

Governance in Bihar today

In Bihar itself, reforms have been diluted by bureaucratic blockages, village-level politics, and the imperatives of coalition government, which have recently thrown Kumar and Yadav into an ad-hoc coalition of contrasting governance styles.

The survey: a comparative analysis of Bihar and Jharkhand

This research takes advantage of the administrative separation of the Bihar and Jharkhand states in 2000 to estimate the political effects of governance reform. Respondents on the Bihar side of the border live in very similar circumstances, but their experience of governance is now dictated by decisions in Patna rather than Ranchi, exposing them to more programmatic governance. The analysis compares the survey responses of individuals living within 4km of the state border, using a geographic regression discontinuity (Dell, 2010) to look for sharp changes in attitudes and behaviours at the border.

The results

The results from 3,514 respondents show that governance differences have had major effects on political expectations, attitudes and behaviour. In the short-term, Kumar’s policy reforms succeeded in inducing voters to support his reform agenda. Despite voters’ poverty and the strength of clientelist threats, the evidence suggests that programmatic reform played a vital role as a coordinating device, enabling voters to have collective confidence that each would resist the clientelist threat and vote for programmatic reform. This weakened the clientelist trap and coordinated voting around the re-election of Kumar.

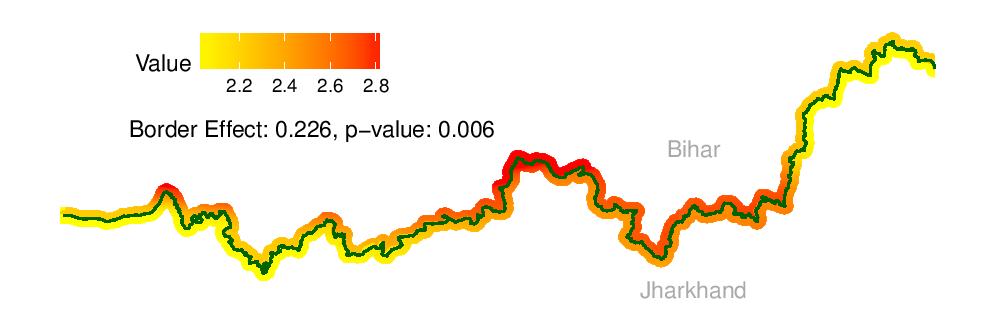

The results show, for example, that Biharis have strong expectations of public benefits if they re-elect the incumbent Chief Minister and, as Figure 1 illustrates, are much more confident that other voters will sanction poorly performing Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs).

Figure 1: Predicted value of perceived likelihood (5-point scale) that other voters will sanction poorly performing MLAs.]

Limits of reform

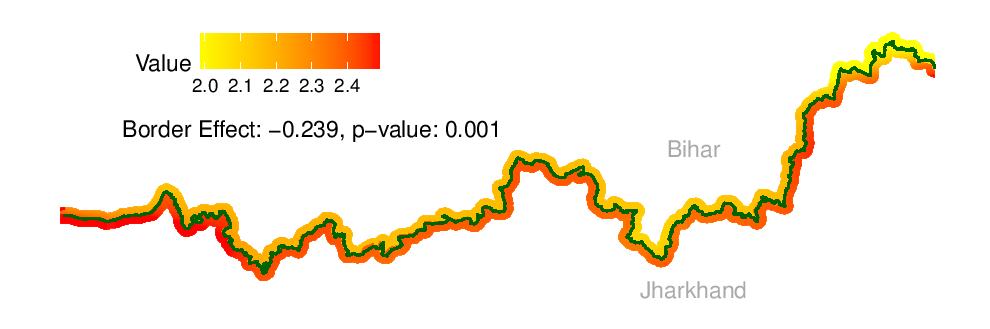

However, a side-effect of governance reform is that as Biharis loosened their ties to clientelist networks, they no longer constantly mobilised for political ends and, as a result, have become disengaged from and sceptical of politics. The results indicate, for example, that Biharis are less likely to attend Gram Sabha meetings and are less trusting in institutions (Figure 2).

Perhaps most importantly, a hypothetical conjoint survey experiment indicated no difference in Biharis’ willingness to elect clientelist or programmatic candidates, suggesting that the voting coordination effect of reform may not extend beyond the incumbent’s period in office.

Figure 2: Predicted values of Trust (5-point scale) in the civil service

Conclusion

The challenge for reformers, then, is to deliver highly visible and widely recognized improvements in service delivery while keeping citizens engaged in politics. In policy terms, the results highlight the importance of making public service improvements as inclusive and widely shared as possible – each voter must be confident that as many other voters as possible have benefitted, and will therefore be inclined to take the risk of abandoning clientelism. Marketing these reforms is crucial to creating a sense of common knowledge that the incumbent has delivered enough benefits to warrant re-election.

As bureaucratic reform thins clientelist networks, mitigating efforts to mobilise voters to participate in politics, replacing personalised trust with generalised trust in institutions may also be required. These may demand greater bureaucratic transparency, alternative avenues of participation, improved economic security, and more durable, disciplined political parties with a reputational stake in ongoing reform.

If Bihar is to surprise the world again and embed sustainable governance reforms it will need to transition from policy reforms to institutional reforms that anchor a long-term shift in citizens' attitudes, expectations and behaviour.

References

Greenstone, M., Burgess, R., Ryan, N. and Sudarshan, A. (2013), Lighting up Bihar, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/lighting-up-bihar/

Afridi, F., Iversen, V. and Sharan, M. R. (2013), Assessment of MGNREGA Divas, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/assessment-of-mgnrega-divas-2/

Prakash, N. and Muralidharan, K. (2013), Cycling to school: Increasing high school enrollment for girls in Bihar, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/cycling-to-school-increasing-high-school-enrollment-for-girls-in-bihar/

Kumar, H. and Somanathan, R. (2013), Evaluating the effects of targeted transfers to ‘Mahadalits’ in Bihar, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/evaluating-the-effects-of-targeted-transfers-to-mahadalits-in-bihar/

Kumar, S. and Prakash, N. (2012), Women’s Reservations in Bihar and Children’s Health Outcomes, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/womens-reservations-in-bihar-and-childrens-health-outcomes/

Das Gupta, C. and Haridas, KPN (2011), Role of ICT in Improving the Quality of Elementary School Education in Bihar, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/role-of-ict-in-improving-the-quality-of-elementary-school-education-in-bihar/

Verma, P., Kumar, C. and Gahlaut, A. (2014), Social Justice in Education: Are School Uniform and Scholarship Schemes Marred with Discrimination in Bihar, Project of the International Growth Centre, Accessible: http://www.theigc.org/project/social-justice-in-education-are-school-uniform-and-scholarship-schemes-marred-with-discrimination-in-bihar/