Can deliberative democracy cure Tanzania's resource curse?

Experts worry letting ordinary citizens manage resource windfalls will lead to populism. We ran a randomised trial in deliberative democracy in Tanzania to find out.

This is the first post in a three-part blog series on political transparency of natural resource management and has a related podcast.

Are low-income democracies doomed to squander their natural resource wealth?

Tanzania is one of the poorest democracies in the world. Elections this October will mark twenty years of multiparty democracy, and yet three-fourths of the population still lives under $2 a day.

But recently Tanzania discovered natural gas reserves that are projected to yield anywhere from $15 to about $75 per capita in government revenue each year – depending on global commodity prices and a complex set of policy and investment decisions still pending. While $75 might sound paltry, it’s roughly equal to the median Tanzanian’s total food consumption in a year.

A few months back, we blogged here about an ongoing public opinion poll we were running with REPOA, a Dar es Salaam think tank, asking Tanzanians what they expect from natural gas, and what they would do with this windfall if and when it arrives.

[embed]https://youtu.be/lUaX44Md8DA[/embed]

In private conversations, many experts were sceptical that Tanzania’s poor, rural electorate could provide useful input into an often technical policy debate about natural gas. (“Populism!”) We decided to embrace that challenge. We teamed up with Jim Fishkin and co of Stanford University, who specialise in a process they call “deliberative polling.” We started by running a standard, nationally representative poll. Then we brought together 400 respondents from our sample of 2,000 for a two-day extravaganza in deliberative democracy, including educational videos, small group discussions, and Q&A with experts in economics and in the gas sector..

After everybody went home, we polled them again – along with a control group that wasn’t invited. In sum, we ran a nationally representative, randomised experiment in deliberative democracy. Here’s a snapshot of what we found in terms of (a) what Tanzanians think, and (b) how those views changed as they got more information and spent time deliberating.

Timeline for the experiment:

- February 2015: We surveyed 2,000 randomly selected Tanzanians about their knowledge and opinions of natural gas policy.

- March 2015: We invited 700 of those respondents (chosen at random again) to “information sessions” where they watched educational videos about natural gas policy and other countries’ experiences.

- April 2015: We invited a random 400 of the 700 to a two-day deliberative event, where they debated gas policy in small groups, and asked questions to gas researchers, politicians, and bureaucrats.

- May 2015: We polled all 2,000 people again, to see how their opinions had evolved.

Details of the experimental design are available at the American Economic Association’s RCT registry.

Result #1: Tanzanians are responsive to arguments against fuel subsidies

Tanzanians are more market friendly and, well, neoliberal than we expected from a formerly (and still nominally) socialist country. Take the example of fuel subsidies.

Many developing countries spend huge amounts of money on fuel subsidies that are highly regressive and distortionary – benefiting rich people with cars and generators, and encouraging use of dirty fossil fuels. Economists at the IMF and elsewhere have been trying to wean countries off these subsidies for years, but attempts to dismantle them have led to massive protests, as in Nigeria last year. The problem is that where median consumption is as low as in Tanzania, the “right” price for electricity and fuel is likely to hit the poor hard ; a progressive solution is cash transfers targeted to the poor to offset higher energy prices – but see results forthcoming in part II of this post on that.

When we asked Tanzanians point blank whether the recent natural gas discovery should be used to make fuel and electricity cheaper, a strong majority said “yes.” But when this question was posed as a trade-off between selling gas to generate revenue for other purposes, versus using it to make electricity cheaper, a majority chose the former.

That result was true of the entire sample. But the deliberative poll tells us there was more to the change than an appreciation of opportunity costs the trade-off question evoked. It was also the case that the more people learned, and the more they thought about the issues, the stronger their support for extracting natural gas, selling it, and using the revenue to pay for Tanzanians’ needs.

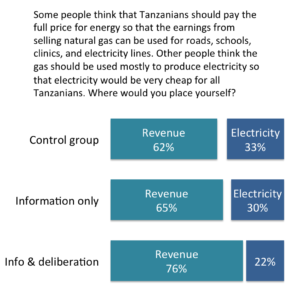

The poll shows that 62% of Tanzanians in the control group supported selling gas for revenue over electricity subsidies (Figure 1); once they had watched the informational video 65% voted for more revenue. The big change came in the group that participated in two days of discussion and deliberation, in which 76% supported monetizing the gas – which implies a highly significant treatment effect from deliberation.

So are Tanzanian voters all orthodox economists at heart? Not quite.

Figure 1. Sell gas for revenue vs. use for electricity

Result #2: Even after deliberation, voters have little interest in saving gas revenues for the long term

The average Tanzanian voter is probably not quite ready to hand over the economic reins to the orthodox solution of saving via a sovereign wealth fund (long viewed as the favored approach by the IMF and the typical central banker in both developing and developed countries). On the one hand, the orthodox solution is far too stingy – and especially so in poor countries that are growing, where future generations are likely to be richer than the current one anyway. On the other, it’s risky too – even a sovereign wealth fund can go astray. Most Tanzanians support the impulse to spend typically associated with natural resource booms. Contrary to “IMF orthodoxy” that most revenue be saved and consumption smoothed over time, 72% of Tanzanians prefer to spend natural gas revenues sooner rather than later.

Ensuring good governance in the face of a potential resource windfall will require broad public understanding of difficult policy choices to help shield citizens from opportunistic political arguments.

That preference for spending didn’t decline whatsoever when confronted with information about boom and bust cycles in other countries, or given the chance to deliberate.

When probed for what they want to spend the gas money on, 61% voted for social services like health and education over the alternative of roads, power, and infrastructure. This preference strengthened with deliberation, rising to a 71% majority. This is not to say Tanzania doesn’t need infrastructure investment; the preference for social services probably reflects demand for services that address Tanzanians’ very basic unmet needs for health and education.

Result #3: But there’s a limit to Tanzanians’ appetite for spending: they oppose leveraging gas to borrow overseas

Since 2013, Tanzania has been flirting with the idea of entering the sovereign bond market, with a debut offering of up to $2 billion in new debt currently planned for later this year or 2016. The timing is notable. Regardless of whether Tanzania makes any deliberate attempt to use gas as collateral (which is less likely than it might have been given Ghana’s recent experience), bond markets will likely build the new gas reserves into their calculus of Tanzania’s credit worthiness.

Interestingly, although Tanzanians are eager for government to raise spending on education and health, a slim majority are unwilling to support using gas as collateral to borrow and spend before the gas revenues arrive. Deliberation did little to change people’s views on debt. In the control group 51% opposed borrowing (compared to 45% in favor), while 53% of those who participated in deliberation opposed borrowing, compared to just 42% in favor.

Process lessons: Letting people talk beats talking at them

One of the broader “meta-“ questions we wanted to address in this study was whether deliberation per se really matters. Perhaps voters are just uninformed, and a simple, cheap information campaign could set them straight without the chaotic (and costly) process of facilitating public deliberation.

Results suggest otherwise.

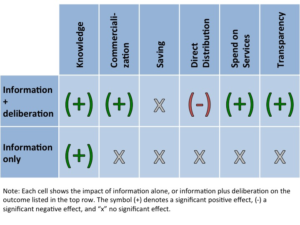

Deliberation had significant impacts on five of the six broad outcomes we measured (Figure 4). Participants’ knowledge of natural gas went up, which is not surprising but a little reassuring. They shifting in favor of extracting and selling the gas, rather than using it to subsidise domestic energy, but didn’t change their mind about saving. In addition, deliberation participants became significantly more skeptical of cash transfers, and significantly more enthusiastic about transparency and oversight measures. (In future posts, we’ll delve deeper into these last two topics.)

In contrast, people who only watched the informational video but weren’t invited to participate in deliberation showed no significant opinion changes. Their objective knowledge increased, but that’s all. From commercialisation to saving to transparency issues, learning more about gas didn’t affect their views.

Figure 2. Summary of experimental treatment effects on Tanzanians' knowledge and policy preferences regarding natural gas

Score a point for deliberative democracy, and a strike against the idea of running information campaigns to simply “educate” voters.

In a democracy like Tanzania, choosing how to use natural resources shouldn’t be reserved for technocrats. The fact that people’s carefully considered opinions on gas policy differ significantly from their naïve first reactions demonstrates that ordinary Tanzanians – mostly rural, many illiterate and poor – have the capacity to wrestle with complex policy issues.

Ensuring good governance in the face of a potential resource windfall will require broad public understanding of difficult policy choices to help shield citizens from opportunistic political arguments. This deliberative poll provides some evidence that building that understanding is possible, and a hint about how to get there.

This blog was originally posted here on Center for Global Development’s website. This is the first of a three-part blog series on managing natural resources and has a related podcast. Part II looks at cash transfers, and part III at transparency.