Click to apply: The impact of online job portals on job search outcomes

India has one of the largest and fastest growing populations of internet users in the world. An estimated 190 million Indians use the internet, up from 7 million in 2001. Approximately 40 million Indians go online every day, using the Internet to make purchases, access financial services and education, and interact with friends and family. In a recent IGC project Jeremy Magruder studies the effect of online job portals on labour market and job-matching outcomes.

The proliferation of internet access has made it a well-accepted tool for millions of job seekers, searching for both formal and informal jobs. At the forefront of this surge, are job portals connecting prospective employees with potential employers. The popularity of portals has grown significantly in the last 10 years responding to the evidently growing need to better link the two groups. According to the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry employers frequently complained about the difficulty of filling vacant positions despite pervasive unemployment among semi-skilled labourers, and the glut of recent technical and vocational graduates.

Job portals are a simple, but effective tool. They create space for employers and employees and provide easier access to a wide array of jobs in different sectors and skill levels. They also reduce job-matching costs and fees associated with middlemen and head-hunters.

Job portals have also expanded equality of access to employment. Prior to their existence, social connections and informal networks were the dominant means of searching for employment. Job-hunting through social networks tend to favour well connected individuals, further entrenching existing inequalities. Equality of access to online portals can mitigate this implicit discrimination in access to both formal and informal jobs.

Can job portals improve job searching and matching?

To date, there has been little focus on understanding how job portals actually benefit job seekers in the developing world. A new IGC project provides a rigorous assessment of the value of job portals – examining their effect on labour market outcomes for job seekers.

The study uses a new job-matching platform where employers are provided with the names of job-seekers, including recent graduates from vocational schools. The platform is easy to use, and allows employers to send SMS messages to qualified candidates. Employees then follow up directly with the employer to set up interviews. The postings span many different trades, including logistics, transport, services and telecoms.

The study uses a randomised control design to answer the following two questions:

(1) How does the portal affect outcomes for recent public vocational training graduates?

(2) How does receiving a priority ranking on the portal affect outcomes for job seekers that are registered on the portal?

Job portals may reduce inequality in accessing jobs

Looking at the baseline data gathered for this study, we tackle two important questions for assessing the value of job portals. First, we investigate whether internet and job portals are equally accessed by the entire sample of job seekers in our dataset. Specifically, we contrast different groups of job seekers: recent graduates (those not yet using the study’s job portal) vs. more experienced job-seekers[1] (already enlisted on the portal); high caste vs. lower caste job seekers; and rural vs. urban job seekers. Second, we explore whether internet and job portal usage is correlated with better employment outcomes.

Job portals have also expanded equality of access to employment.

In regards to the first question, an analysis of the baseline data shows that recent graduates – perhaps surprisingly – use the internet significantly less to find jobs than more experienced job seekers, and tend to be registered with fewer portals.

The study finds 78% of seasoned job seekers used the internet to search for employment opportunities, versus only 64% of recent graduates. More experience job-seekers were also more likely to register on more than one job portal and relied less on social networks (friends, immediate family, classmates, relatives, etc.) than recent graduates. The latter may reflect differences in perceived value of social networks across difference groups. At the baseline, when asked to rank the usefulness of their social network in finding jobs, recent graduates consistently ranked their social connections higher than more experienced job seekers ranked their own.

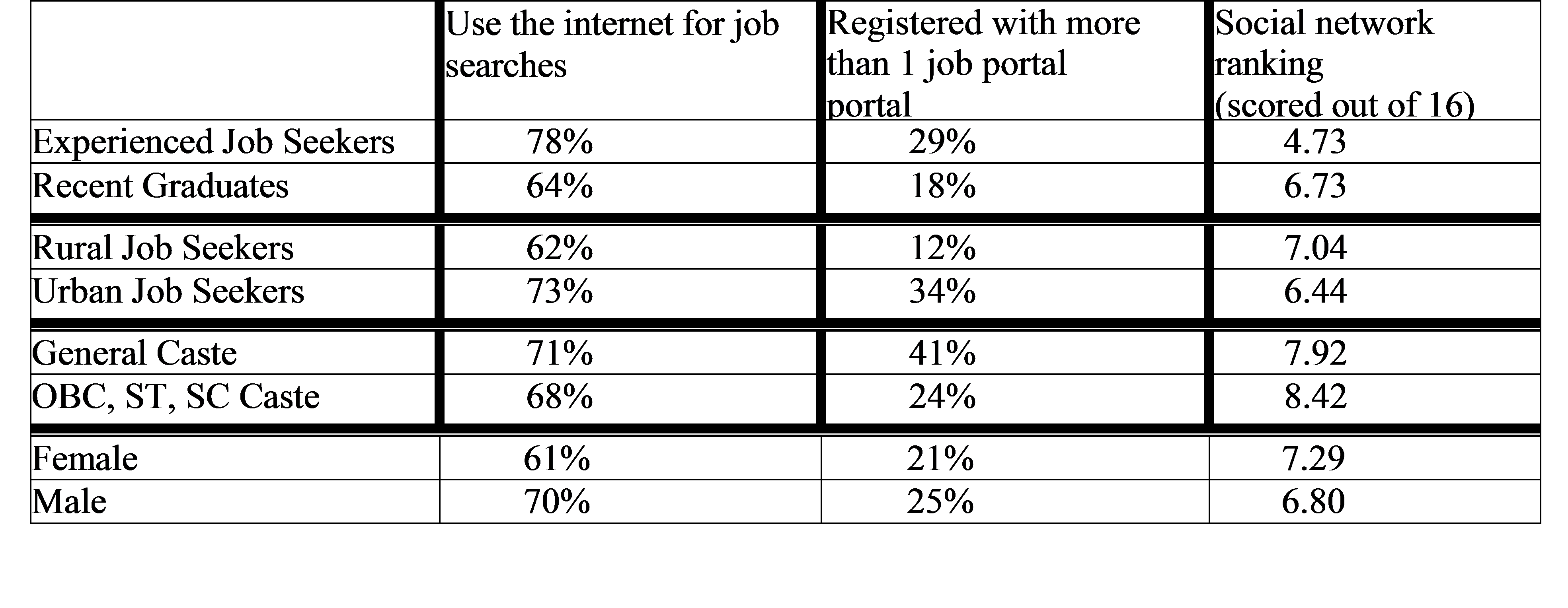

These same patterns: 1) lower internet usage 2) less knowledge of job portals, and 3) higher reliance on social networks, are also observed among Scheduled Castes (SC), Schedules Tribes (ST), and Other Backwards Castes (OBC) (relative to general castes), among rural job seekers in villages (as compared to those in more densely populated urban areas), and among females (versus males). Table 1 below quantifies these differences:

Table 1: Comparing internet usage, portal registration, and social network across different groups of job seekers

More experienced job-seekers were also more likely to register on more than one job portal and relied less on social networks (friends, immediate family, classmates, relatives, etc.) than recent graduates.

These results suggest that while the internet and job portals are helping job seekers find employment, the extent to which certain groups utilise these tools differs. More intensive internet job searching also lowers an individual’s reliance on social networks, which could help certain groups overcome inequalities that might otherwise be associated with traditional job search avenues.

How do internet usage and social networks relate to employment outcomes?

We asked job seekers for a detailed account of their employment history, and elicited the minimum salary they would be willing to accept if they were offered a job in their sector (reservation wage). Lower reservation wages may mean that workers have less patience in the job search, or worse prospects of finding a high quality job.

The data reveals that job seekers registered with job portals are approximately 6% more likely to be employed and their reservation wages are 1300 rupees higher (a 10% increase over the mean), relative to those who do not rely on the Internet. We also find that currently workers, who are registered with portals, have higher actual wages (13%) than employed workers who aren’t registered with portals. Conversely, workers who derive greater assistance from their social networks have slightly lower chances of being employed and lower associated reservations wages.

Conclusion

Initial results suggest that using the Internet, and relying on job portals is associated with positive impacts on employment outcomes and higher reservation wages for certain groups over others. This includes more experienced job seekers, higher caste persons, urban job seekers, and women. Conversely, recent graduates, lower castes, women and rural job seekers rely relatively more on social networks, which seem to be less effective. We do note that the results discussed in this blog are still preliminary, and we urge caution in interpreting them, as they are correlations and may not explain causality of effects.

If however, further results do support our initial hypothesis, we believe that job portals may prove a useful tool for increasing the rates of job acquisition among marginalised groups. New recruitment strategies could be targeted towards bringing specific marginalised groups onto the portal, and training them to use the internet and portal efficiently for their job search. Moreover, public vocational training schools can improve their placement rates by assisting their graduates in searching for jobs through the internet and by registering on job portals.

job portals may prove a useful tool for increasing the rates of job acquisition among marginalised groups

Future work will determine if job portals benefit some groups more than others, and if they are doing less to overcome natural inequalities than they could because of ineffective or lower utilisation by disadvantaged groups.

[1] Note these groups are not directly comparable as recent graduates are generally much younger, and have less work experience.