Climate information services to enhance agricultural resilience: Evidence from Ethiopia

Access to climate information services can improve agricultural productivity and farmers' resilience in Ethiopia. Panel data estimates reveal access to existing weather and climate services boosts maize and wheat productivity by about 27% and 17%, respectively, comparable to or higher than the conventional yield-increasing production technologies such as fertiliser and improved seeds.

Agriculture is among the sectors most vulnerable to weather and climate risks. Reviews of the linkage between climate change and smallholder farmers, including the role of Climate-Smart Agriculture in improving agricultural productivity, suggest that unless strategic interventions are implemented, climate variability and extreme weather events will affect smallholder farmers’ agricultural yields. This is likely to result in significant gaps between yields in the affected regions and the global average for major food crops, having significant implications for food security in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This is particularly relevant for SSA economies such as Ethiopia, which rely heavily on subsistence and rainfed agriculture.

Agricultural vulnerability from unpredictability of climate

Among SSA countries, Ethiopia is considered one of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and climate variability. Given that Ethiopia's economy relies heavily on weather-dependent agriculture, it is extremely susceptible to both, extreme weather events and long-term risks related to climate change. Even a slight change in weather conditions exposes a significant number of the country's population, especially those in resource-poor rural areas, to the risk of disaster. Climate change will continue to act as an agricultural risk multiplier, exacerbating such vulnerabilities.

Several studies have documented that extreme variability in weather and rainfall have a considerable negative effect on agricultural GDP, household welfare, and national economic output. According to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Country Index1 (2017), Ethiopia is among the most vulnerable 10% of countries. Weather and climate information services are increasingly seen as foundational for building resilience and enabling adaptation to the impacts of climate change in agriculture and other climate-sensitive sectors. In a recent study, we aim to estimate the impact of weather and climate services on farm productivity of major crops in Ethiopia: cereals, pulses, oilseeds, and coffee. Among cereals, we focus on the four most important staple crops (maize, teff, wheat, and sorghum2).

Methodology

To estimate the causal effect of accessing weather and climate services on crop productivity, we relied on panel data estimation methods, using primary data from a large-scale survey implemented as part of a Feed the Future (FtF) survey. The survey was undertaken across five major administrative regions of Ethiopia (Amhara, Oromia, Tigray, SNNP, and Somali). The survey covers only rural areas across three major agro-ecologies: 'moisture reliable', 'drought prone', and 'pastoral.' Data collection was conducted in three rounds (2013, 2015, and 2018) for baseline, midline, and endline survey, respectively. We have a total of 3,799 households for each survey round.

Access to weather and climate services remains limited

Only 18 % of the farming households accessed weather and climate services. Of those farmers who accessed these services, 73% confirmed that they understood the information they received, 45% stated that they received the services on time (that is, well before the growing season), and 40% believed that the services they received were adequate.

Among the farmers with access to weather and climate information, the details of information received varied:

· 31% received daily weather forecasts

· 27% received rainfall onset and cessation forecasts

· 20% received rainfall onset forecasts

· 15% received ten-day forecasts

· 6% received warnings of the occurrence of flood and drought

· 16% received combinations of these services.

What information is useful and when?

Respondents were asked about what they considered the most useful weather and climate information.. Respondents gave the highest priority to information on rainfall onset and cessation dates (31% of farmers), followed by daily forecasts (20%), forecasts of rainfall onset (16%), and combinations of the different types (23%). In contrast, the occurrence of flood and drought (5%) and ten-day forecasts (5%) were considered less important.

Among farmers who had access to weather and climate services, the crucial times for receiving weather and climate services were during planting (16%), at times of agrochemical application (35%), in cases of extreme events (15%), and some combination of all of the above(34%).

Access to media and information

For receiving information, 63% of the farmers identified radio, and 19% identified television, as their preferred mode. Another 8% mentioned extension agents, and 4% mentioned friends/neighbours as their preferred mode of dissemination.

Interestingly, only a few farmers (2%) identify mobile phones (SMS) as a good modality of dissemination. This could be due to the low literacy rate in rural Ethiopia (one needs to read SMS messages to understand the content), as well as due to limited mobile access. The latter is an issue even for extension agents.

Farmers identified media use (which included access to media, and suitable timings of airing of content) and financial constraints as the two most important challenges to accessing the information, with each mentioned by 18% of respondents. Language of service communications was a major challenge for 8% of respondents, while 6% reported a lack of decision making among the challenges. While 33% of respondents reported no constraints to acting on the information , this figure may include both, persons who were not interested in using these services, and those who felt that the information provided to them was in fact sufficient to act upon.

Access to weather and climate services leads to substantially higher agricultural productivity for maize and wheat

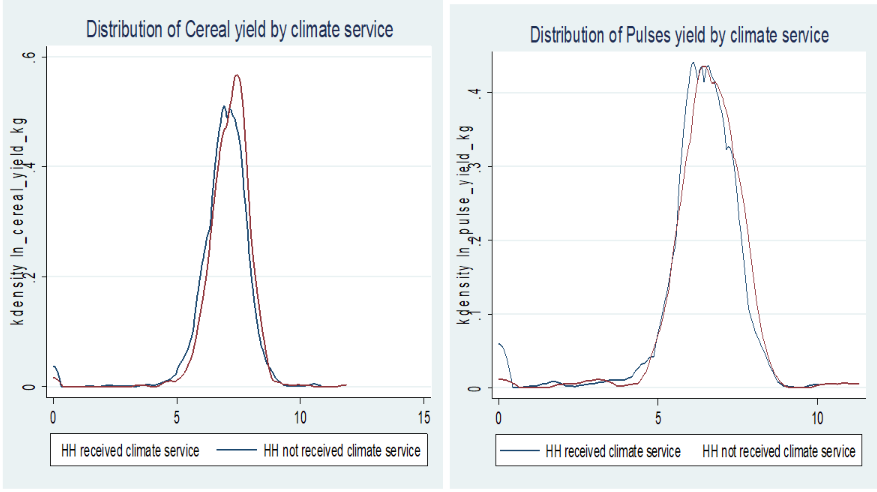

Figure 1 shows estimates of the effect of access to weather and climate information on the average yield of cereal and pulses. The figure on the left displays the association between households’ access to climate service and cereal yield; on the right is the graph for pulses yield. Access to climate information enhances the yield of cereal crops by approximately 17% higher yield as compared to household that did not have access to climate service. However, there is no such observed effect of receiving climate information services on the yield of pulses.

Figure 1: Access to climate service has impact on the average yield of cereals, but not on pulses

Source: Authors' computation.

Amongst the four most important cereals (teff, maize, wheat, and sorghum),, the impact of access to weather and climate services seems to vary by crop. While access to these services seems to have little effect on the productivity of teff and sorghum, it leads to a considerable productivity gain for maize and wheat. To put this into perspective, we compared the productivity gains from access to CIS to those from conventional productivity-enhancing inputs, such as the application of fertiliser). We found that gains from the application of fertilisers lead to only 8% and 12% productivity gains in maize and wheat yields, respectively; in comparison, gains from climate information led to 27% gains in maize productivity, and 17% gains in wheat productivity.

Conclusion

To enhance access to such services, we believe it would be useful to unbundle and analyse different components of climate and weather information, including the nature of information and how it is disseminated. Further analyses are needed to estimate the value to smallholder farmers of better seasonal climate forecasts, as well as the cost effectiveness of alternative channels for delivering time-sensitive information, whether through continued reliance on radio/TV media, mainstreaming into Ethiopia's agricultural extension system, or supporting farmer decision-making with advisory tools and training.

Editor's note: This article is part of our climate change series exploring the challenges and opportunities of promoting a low-carbon, sustainable future in developing countries.