Health and environmental impacts of brick kilns in Bangladesh

Brick kilns are a major source of air pollution in Bangladeshi cities. Not only do they pose serious health and pollution risks, but also contribute to widespread labour rights violations. Research and policy should focus on identifying feasible alternatives to bricks and strict monitoring of the industry.

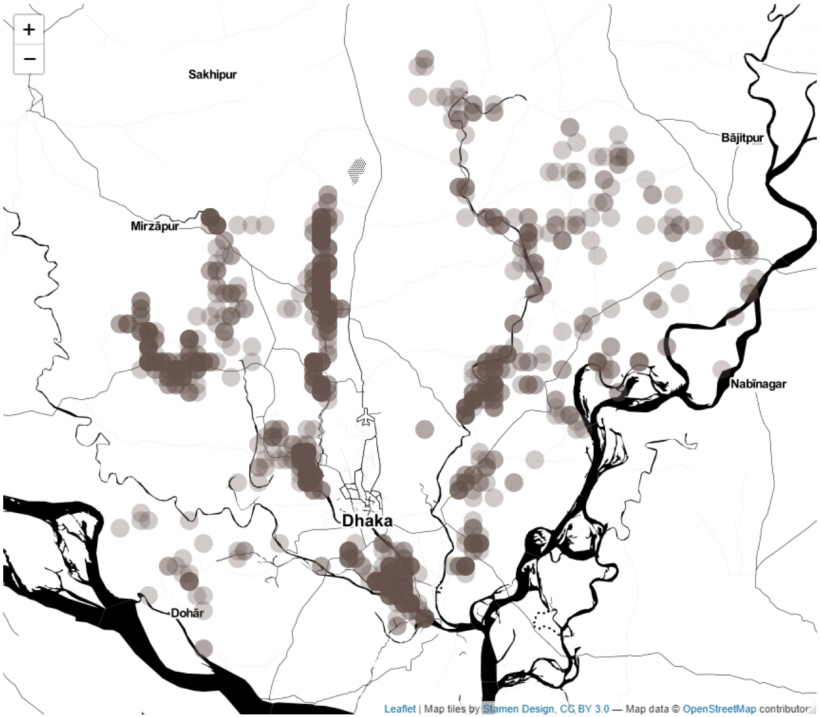

The fundamental component of construction, bricks and brick kilns have grown with the Bangladeshi economy in the last decade. In 2013, the number of brick kilns was around 5000. This grew to 8000 by 2018 – a 60% growth in five years. Brick kilns have negative environmental and health impacts, especially because of the dated manufacturing technology and proximity of kilns to major cities with large populations. Further threat is posed by the spatial density of brick kilns. These kilns are usually clustered in certain areas, sometimes close to major rivers and adjacent cities. This poses serious health risks to Dhaka city residents during brick manufacturing season which runs from December to April. The Department of Environment (DoE) reports that around 58% of fine particles in Dhaka air come from brick kilns.

Figure 1. Dhaka is surrounded by clusters of brick kilns. This image shows the location of 1252 kilns around Dhaka. Each circle represents one or more kilns (deeper colour indicating the presence of more kilns in one location). Data: Department of Environment, Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC)

Types of Brick Kilns

Fixed Chimney Kilns (FCK) are characterised by a fixed, 120-feet long chimney, low construction costs (around US$60,000) and high particulate matter emissions.

Zigzag kilns are characteried by zigzag air flow in the kiln, improving the combustion of fuel and heat transfer. The Improved Zigzag Kiln (IZK) championed by the DoE in Bangladesh does better than FCKs and regular zigzag kilns in terms of energy use, sulur and carbon emissions. It costs about US$42,000 to upgrade an FCK into a IZK. Low-cost convertibility of FCKs into IZKs is a major selling point for the later.

Hybrid Hoffman Kilns (HHKs) are cost-intensive and highly energy efficient. HHKs require initial capital investment of at least US$2million.

Alternative brick kiln technologies and barriers to transition

Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has found it difficult to regulate the brick industry. Brick manufacturing has been a necessary component of Bangladesh’s growth, especially since the construction boom of the last decade. Around 90% of the 8000 brick kilns in the country are Fixed Chimney Kilns (FCKs). Compared to modern technologies such as Improved Zigzag Kilns or Hybrid Hoffman Kilns, FCKs consume more coal, emit more particulate matter, and generate more sulphur dioxide. The government has taken measures to move away from FCKs and adapt modern, cleaner technologies. Initially, Bangladesh placed its bets on Zigzag Kilns but quickly discovered that entrepreneurs were not constructing and maintaining the kilns properly. Very little was thus achieved from these kilns in terms of energy efficiency or pollution control.

On the other hand, an initiative campaign for popularising Hybrid Hoffman Kiln (HHK) was launched by the UNDP but the responses were slowbecause HHK was the most capital-intensive and expensive technology. Later, the World Bank and Department of Environment (DoE) worked with Hanoi University to develop a cheap method to convert traditional Fixed Chimney Kilns (FCK) to Improved Zigzag Kilns (IZKs). IZKs provide better heat insulation, prevent penetration of water, and trap particulate matter inside the kiln.

GoB’s stated goal to solve this problem is a multi-phased transition. In the first phase, government wants FCK owners to move towards newer technologies like IZKs and HHKs. With time, GoB expects, construction in the country will be increasingly based on concrete blocks rather than bricks. However, the transition is capital-intensive and owners are reluctant. Government, for their part, acknowledges that the push to move away from FCKs has not been well coordinated. Some owners complain that they transitioned to Zigzag kilns at the behest of the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) only to find the same ministry asking them to transition to HHKs a few years later. MoEFCC is now concentrating on HHKs and concrete blocks as the final frontier.

Monitoring and enforcement of brick kiln regulations is lacking

With the necessary regulations passed and technological alternatives in place, there were reasonable expectations for positive changes in the brick kiln industry. In 2018, the World Bank and DoE partnered with Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh to create a GIS-based inventory of all brick kilns of the country. This project identified almost 8000 brick kilns throughout the country. The idea was that such an inventory would enable DoE to effectively monitor the industry.

Reports suggest that DoE mobilised its workforce to crack down on illegal establishments, occasionally responding to complaints from local farmers. However, there are cases where illegal kilns resumed operation in the season after their operations were stopped. There are also complaints that the DoE inventory is not up to date and is missing many kilns.

Another concern regarding enforcement is if regulations are unnecessarily too strict. The brick manufacturing and brick kilns establishment (control) act states that kilns cannot be established within a kilometer of city corporations, residential, commercial, ecologically critical area, agricultural land, public or private forest, etc. In a country as densely populated in Bangladesh, enforcing this law will mean that there will be virtually no place to establish a kiln. The four rivers surrounding Dhaka city are all declared as ecologically critical areas. If the law is enforced, then no brick manufacturing can take place near these rivers. However, majority of brick kilns in Dhaka are located close to these rivers due to advantages in transportation and availability soil from river beds. Rather than trying to relocate hundreds, if not thousands of kilns, the law probably should have focused on use of modern technology.

Labour rights violations of brick kiln workers

Amidst all the efforts to address the pollution by brick kilns, other concerning issues such as kiln workers’ rights is often neglected and understudied. A 2017 study reported that brick kiln workers suffer from extreme heat, flying dust, lack of safety arrangements, and absence of any job security. More than 50% of the workers report blurred vision and eye injury, and frequent respiratory distress due to prolonged exposure to the polluted environment. Additionally, multiple studies in different regions report that lack of proper water and sanitation arrangements are common in kilns. To add to these sufferings, workers also report poor pay with around 30% getting paid lower than BDT 10,000 (approximately US$ 100) a month.

There are also allegations that workers are sold to kilns by brokers or their own families to repay debt taken from the kiln managers. In 2018 and 2019, police have rescued 108 workers who were tortured and, in some cases, shackled and forced to work in the kilns. Unfortunately, the real number of people facing harassment is likely to be far higher and harder to estimate. The Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishment (DIEF) itself concedes that it is difficult to monitor the industry because of capacity constraints.

Policy and research implications

The IGC Bangladesh country team is currently working to establish a formal partnership with DoE. Issues like lead pollution and brick manufacturing are on the list of items that we aim to collaborate on. Researchers can leverage the rise of remote sensing and machine learning and use that to create an updated inventory of brick kilns in the country. This would include not only the number but also the type and status (active versus inactive) of brick kilns. Similar work has been done in the past by DoE in 2018 but the database needs to be updated. Research efforts should also focus on identifying ways of incentivising DoE workers to crack down on illegal kilns. While this may seem like routine work, doing so is extremely difficult amidst a culture of non-compliance and the potential political and financial muscle of the kiln owners.

Another stream of research should investigate the issue of workers in light of the much sought after transition to improved technology. While modern alternatives can reduce pollution, the impact of this transition on workers is still unclear. Does this transition guarantee a better working environment? Do we know enough about any plausible loss of jobs due to this transition? The job will not be complete with just the reduction in pollution levels, and will need to also firmly end the abuse meted out to the marginalised workers.

Brick kilns are important for the rapidly growing economy of Bangladesh and will remain so until a viable alternative to bricks is found. In the meantime, a concerted effort by the research community, the government, and development partners is needed to stop the environmental pollution and protect labour rights.

To learn more about the climate priorities in developing countries discussed during the LSE Environment Week view the policy memos tabled and other recordings here and read IGC’s latest growth brief on sustainable growth for a changing climate.