How information ahead of floods can improve climate resilience: Lessons from Mozambique

Providing flood risk and mitigation information to households through digital channels like text messages improved community-level collaboration in Mozambique. Scaling such information campaigns can be an effective way to foster resilience towards climate shocks.

Floods are among the costliest and most recurring natural disasters, especially in urban centres around the equator. According to the International Disaster Database, from 2010 to 2021, floods affected 758 million people worldwide and resulted in total estimated damages of US$ 583 billion. Urban flood risk will likely increase in sub-Saharan Africa due to rapid urbanisation, overcrowding of vulnerable residential areas, and climate change trends. To prepare and warn citizens, many governments provide some form of disaster preparedness information, but relatively little is known about whether and how such policies change behaviour.

In my study, I use a randomised controlled trial to test the effectiveness of low-cost, scalable information interventions. Quelimane, Mozambique’s sixth-largest city, is highly vulnerable to flooding. Together with the local authorities, I designed and carried out three interventions that bundled flood risk information with practical examples of mitigation strategies, such as keeping valuables safe and making home improvements. The interventions emphasise that it is essential to clear drainage canals of solid waste that can block them and exacerbate flooding.

The interventions were implemented in the months preceding Mozambique's 2021-2022 wet season. Three interventions, which varied in the saturation and medium of information disbursed, were implemented across 300 communities:

- The community leader and two households receive the information through a video.

- The community leader and about 30% of the households in the community receive the information through text messages.

- The community leader and about 30% of the households in the community receive the information through both video and text messages.

Houses were randomly allocated to these treatment interventions and were compared against a control group that didn’t receive any information intervention. This research experiment design enables me to test whether informing more people within a community facilitates collective action towards flood mitigation measures. The variation in information medium allows me to test the effectiveness of short messages relative to a more elaborate video.

Using image recognition technology and survey data to measure behaviour

To objectively measure behaviour, the field team made observations about the presence of waste across pre-specified locations along drainage canals (every 50 metres) and streets (at randomly selected points) during the wet season. The team members also took photos in each place. I use a machine-learning algorithm to classify these 25,000 photographs and turn them into data. The vision-language model enables me to ask questions about any image, such as “is there waste?” (Figure 1). The use of image recognition technology to classify cellphone photos in field experiments is novel and has the potential to be applied across a wide variety of topics.

Figure 1: Photo analysis using a vision-language model - two examples

Notes: The figure above shows two examples of photos used to inform the machine-learning algorithm

I also analyse survey data collected from 3,000 households after the wet season to estimate treatment effects. Specifically, I measure the adoption and implementation of the suggested mitigation strategies at home and in the community. Common risks associated with survey measures are the possible biases introduced because of the respondents’ beliefs about appropriate behaviour and the tendency to answer questions in a socially desirable way. The photo analysis addresses these concerns. Moreover, the study discusses survey questions that check for biased responses and survey methods less prone to those risks.

Providing flood mitigation information improves waste management

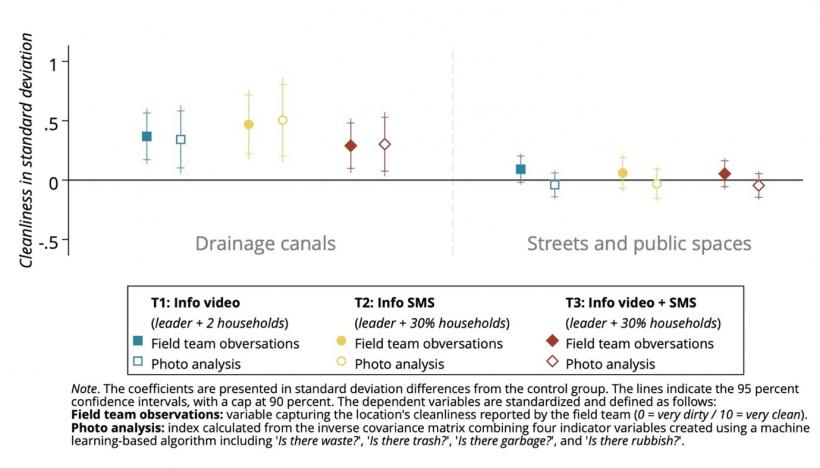

Providing information significantly reduced the presence of flood hazards. Figure 2 shows that drainage canals and surroundings were between 0.29 and 0.51 standard deviations cleaner across the treatment groups as measured by both objective outcomes. This impact is equivalent to a reduction of 8-15% of photos with waste in and around drainage canals. There is no impact away from the drainage canals, suggesting that targeted efforts were made rather than general solid waste management improvements. Surprisingly, there was no statistically significant difference in the effect of information when delivered to a large percentage of households.

Figure 2: Cleanliness of drainage canals and streets

Note: The figure above shows the variation in the amount of waste in and around drainage canals for each of the treatment groups.

The findings using survey data confirm the photo analysis results: providing information increased participation in cleaning and reports of community-level action. Protective action-taking at home and self-evaluated resilience to flooding also improved due to the interventions. On average, targeted families in treated communities were 22-26% more likely to have implemented the suggested mitigation strategies at home. There are no observed meaningful differences between the different information mediums.

Spillover effects of flood information within and across communities

Collective action is essential to address flood hazards like waste. While there are positive externalities to acting, acting alone is not enough and the threat of free-riding is present. I consider these externalities within and across communities. To measure indirect treatment effects on non-targeted households within treatment communities, I analyse survey data from randomly selected households that were not targeted for information. These households also experienced positive treatment effects on flood mitigation behaviours. While these indirect effects are not always significant, they are consistently about half of the direct impact on treated families. This finding suggests that information about risk and mitigation measures diffuses among neighbours, generating positive spillovers and facilitating community-level action.

While spillovers might have been instrumental in impacting community-level behaviour, spillovers to control communities could lead to underestimating treatment effects. This is possible because of the proximity of communities to each other, and drainage canals sometimes mark the boundaries of urban communities. To address this, I estimate the treatment effects on cleanliness while excluding canals on the border between control and treatment communities. Indeed, I find a larger reduction (13-22%) of photos capturing waste. The proximity of communities also means that the control group benefits from actions taken by treatment communities.

Policy implications for improving resilience to climate shocks

This study is relevant for policymakers for two main reasons. Firstly, digital tools like smartphone photos can be used by policymakers to identify vulnerabilities and improve resilience to climate shocks. The photo analysis shows that recent innovations in artificial intelligence and machine-learning can be leveraged to obtain accurate and timely information about important climate risk-related topics.

Secondly, lessons learned from this experiment support and inform communication efforts by policymakers to build resilience to natural disasters in the developing world. Of the urban households in sub-Saharan Africa, 85% own a television and 89% use a cell phone daily. Moreover, the marginal costs of a text message are close to zero. Therefore, providing risk information bundled with examples of mitigation strategies can be a powerful and cost-effective way of improving the resilience of the urban poor.

Future work should focus on expanding this research across scale and time. The findings suggest that providing information more widely is not necessarily better, possibly because of free riding, but what happens when these interventions are tested at scale, and everyone is targeted? In the study, I also discuss how the effect on awareness about flood risks declines after the wet season. Repeating information campaigns seems necessary. Studying longer time horizons could help us understand threats such as declining attention and unsuccessful implementation of suggested actions during past floods.