Collecting tax revenue in Uganda: The carrot and stick story

Text messages focused on enforcement and information are most effective at collecting tax revenue, while encouragement affects the average taxpayer only with visible benefits.

We collaborated with the Ugandan Revenue Authority to test whether and what types of text message reminders help raise government revenue. Specifically, we used an experiment to test how effective different text messages are at encouraging people to pay their share of Uganda’s individual taxes. Our results suggest that which message is sent matters quite a lot in terms of the effect it has on taxpayer behaviour and that – on average – the stick, and not the carrot, is what encourages people to pay their taxes.

The full story, however, is more complicated than that. By using the Ugandan Revenue Authority’s registration data, it was possible to learn something about which types of people were encouraged to pay their taxes owing to these messages. We find that all messages worked best amongst Ugandans living in more remote areas, who had recently seen the construction of new schools, police posts, and local courts. These findings suggest that while both the stick and the carrot matter very much for tax compliance, the medium of the message matters as well. For texts, people react to the stick; when it comes to what they see in the world around them, however, the carrot matters very much indeed.

The experiment

In June 2019, the Ugandan Revenue Authority conducted an experiment to test the efficacy of tax payment reminders amongst over 98,000 Ugandan individual taxpayers, all of whom had at some point paid taxes on revenue from a small business or other source. Three-quarters of these individuals were sent messages on June 28, just before the end of the 2018-19 financial year.

| Group | Size | Message |

| Control | 24,535 texts | No message sent |

| Inform | 24,534 texts | Dear esteemed client, please file your income tax return and pay the tax due by 30th June 2019. URA. |

| Encourage | 24,534 texts | Dear esteemed client, by paying your taxes you make it possible to educate our children, fund our healthcare, and keep us safe. URA. |

| Enforce | 24,534 texts | Dear esteemed client, file your income tax return and pay the tax to avoid unnecessary payment of interest, penalties, and possible enforcement actions like the closure of business. URA. |

The average person in the study was just over 40 years old, and 70% were male. Half were located in Kampala, and the other half were spread out across the country as a whole. On average, people were similar on these sorts of characteristics across the four groups, suggesting that people in the different groups would have been equally likely to pay their taxes if the messages were not sent.

The results

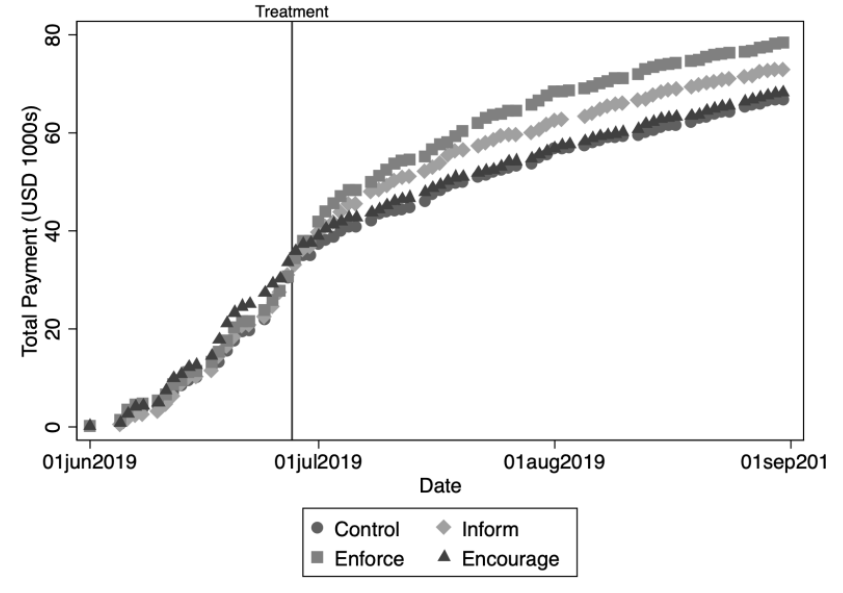

In order to determine whether the treatment had an impact, we compared the taxpaying behaviour of the individuals in these groups after the treatment was implemented. The below graphs show the results of these comparisons on the number of payments made.

Figure 1. Results for payments made

Prior to the treatment date (indicated by the vertical line), payment rates between the control group, the inform group, the encourage group, and the enforce group were essentially identical. After the treatment, however, the groups diverge sharply. Many more individuals from the inform and enforce groups begin to pay relative to the control and encourage groups. These findings suggest that, upon receiving the inform or enforce texts, individuals became more likely to pay their taxes.

These results come mostly from payments for the presumptive tax, and not for the personal income tax. This is true for the enforce treatment, which particularly mentions business closure, but also for the inform treatment, even though the message is very neutral, and not tailored to either tax.

We can also look at the results of the study to determine whether additional money was raised by the Ugandan Revenue Authority. For example, if many people paid a small amount, or some people paid less because they received the text, we might not see any results in increased revenue for URA as a result of these texts. While this is the case for the personal income tax, it is not the case for the presumptive tax.

Figure 2. Results for presumptive tax payment amounts

In total, this graph suggests that from June 28 to September 1, roughly US$ 36,500 (135 million UGX) was raised from the control group via the presumptive tax. From the encourage group, it seems as if the same amount was raised. However, remembering that every group contained the same number of people, roughly US$ 41,000 (152 million UGX) was raised from the inform group, and as much as US$ 47,800 (178 million UGX) was raised from the enforce group. In other words, just by sending these simple text messages, the Ugandan Revenue Authority raised roughly an additional US$ 18,000.

Who paid?

In order to better understand why these treatments worked as they did, it is also possible to look at which people seemed to be more affected by the treatment. We mapped the approximate location of the businesses, and combined this with data on the location of public services (schools, health centers, police posts, local courts and more) to see how what is around a taxpayer changes the way the treatment affects them.

We found that all three text messages worked best in more “remote” places. These are places which do not have high quality schools and health centers and which are further from police posts and local courts. It seems as if the Ugandans who live in these areas were the ones who responded most to the treatment; the effect of the treatment on repayment was greater in more remote than less remote areas.

Very interestingly, the messages were most effective in remote areas where schools, police posts or local courts had been built recently. In other words, the people who responded most to the treatment lived in places with worse-than-average schools, health centers, police posts and local courts, but also where there had recently been efforts made by the Ugandan government to improve the quality of these services.

Lessons learnt

The first main conclusion of the study is that for the average individual paying these taxes, the stick is more effective than the carrot. That different messages had different effects also suggests that tax authorities like URA may want to be careful in the kinds of messages it sends to taxpayers.

The second main conclusion is that what people see around them affects how they respond to these text messages. Individuals who have seen the carrot in practice – for whom the government has recently increased the availability of public services – respond more strongly to the text messages. These findings suggest that improving services delivery may be (partly) its own reward, if it makes some individuals view the government more favourably, and become more likely to pay their taxes.

Both of these questions need further study; for example, we cannot say much yet about the long-term effects of these text messages, or how what people know about taxation affects their response to these messages. However, these results are important as governments like Uganda’s explore how to raise revenue.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any part of the Ugandan government.

Editor’s note: This article is based on this IGC project.