Conflict during COVID-19: Averting a legitimacy and debt crisis in Africa?

Good governance and debt contingency planning are essential for containment and mitigating the economic impacts of the pandemic to avoid a deeper crisis.

The combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising conflict, and escalating debt in Africa is a toxic cocktail that could soon implode. Governments and multilateral lenders need to work out pragmatic ways to neutralise and navigate out of the crisis.

COVID-19: A debt crisis?

Between January and August 2020, the number of conflict-related events in the continent – including political violence, protests, and riots – rose in 43 countries compared to the pre-COVID-19 levels in December 2019 (ACLED, 2020). Fiscal stimulus packages to cushion the impact of the crisis are projected to balloon debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) levels by over 10 percentage points – from an average of 60 percent at the end of 2019 to about 70 percent by the end of 2020 (AfDB, 2020). These levels are reminiscent of the pre-heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) era.

So far, it seems that COVID-19 has taken its highest toll on rich and peaceful countries. Even so, there are legitimate concerns that conflict-affected and fragile African countries may see the virus linger, resulting in protracted economic impacts. This could lead to systemic debt distress in the continent at levels not seen since the debt crisis of the 1980s (IMF, 2020).

In some sense, the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), for which 12 out of 21 fragile and conflict-affected countries enrolled in as of 22 September 2020, is temporarily helping to neutralise the toxic cocktail, with expected debt service suspension of over US$1.01 billion in 2020 alone (World Bank, 2020).

Contagion during conflict

Current evidence suggests that COVID-19 spreads between people through contact with infected droplets (WHO, 2020). Consequently, conflict arenas – such as protests, riots, and war zones – and population displacement encourage the virus to spread.

The hunger and trauma associated with conflicts can cause ill-health, wearing down the immunity of the population. Shelter is also destroyed leaving people dwelling in packed internally displaced persons’ (IDP) camps, with no hope for physical distancing nor appropriate hygiene. Between December 2019 and July 2020, the number of people in IDP camps in the continent rose by more than 10 percent, and the delivery of humanitarian aid to conflict-affected regions has been significantly restricted (DTM, 2020). Moreover, because health systems in conflict-affected countries are weak, treatment is limited. Leaving infected people with little hope for survival.

Containment during conflict

Containment measures as pursued in contexts of peace are hardly applicable in a conflict environment: Mobilising security forces to enforce them creates further risks for conflict and fragility, stressing the already precarious political and economic circumstances (OECD, 2020).

Critically, containment measures increase the governments’ financing demands, requiring the diversion of resources towards additional defense expenditure. This reallocation effect increases the need for debt financing and saps away scarce resources that could be channeled towards health and more economically productive spending (AfDB, 2017).

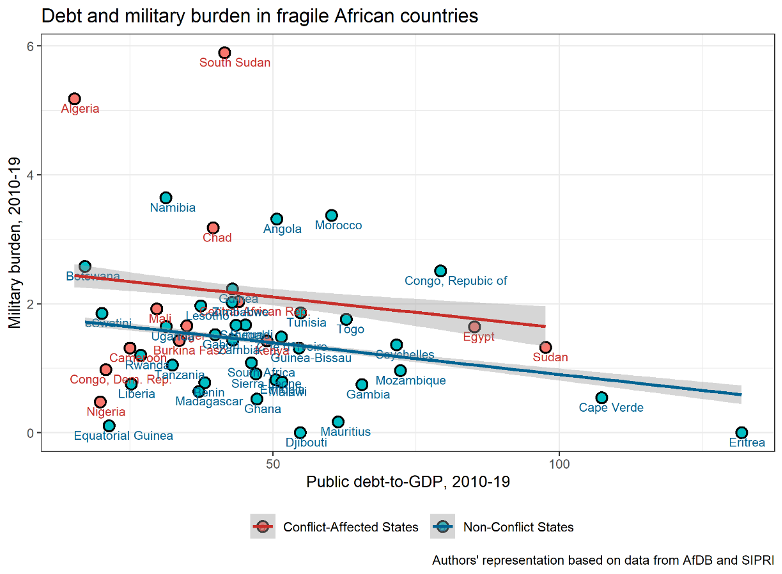

Such a scenario demonstrates why, at any given level of debt, conflict-affected countries tend to spend more on the military than their non-conflict affected counterparts. Accordingly, it can be posited that COVID-19 related debt might be leaking into military expenditure in fragile African countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Furthermore, since most fragile states are commodity-dependent economies, the disruption to global demand and trade for commodities has significantly impacted their foreign exchange earnings. This has contracted revenues and worsened fiscal and debt positions (Brookings, 2020). Moreover, these countries are often unable to access international capital markets because of the uncertainty associated with conflict and the costly premium that creditors may require to lend to them.

Antidotes to Africa’s toxic cocktail

Just like with large-scale natural disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity for countries to address the root causes of conflict, fragility, and debt vulnerabilities.

- Legitimacy and compliance

COVID-19 interventions should be used to close or, at least, bridge existing trust deficits between citizens and governments. This can be achieved if governments and development partners prioritise legitimacy and good governance in addressing the crisis through small, easy steps that yield quick and visible results, as outlined in the Fragility Commission’s report (IGC, 2018).

For example, engaging in wide consultations on COVID-19 interventions and delivering guidance with clear and credible public communication. An all-inclusive and impartial response that targets the most vulnerable groups, while respecting the rule of law and human rights, must be pursued. Historically, catastrophic situations have often been associated with the attenuation of conflicts: Rival parties willing to work together, or at least maintain calm, to focus on preserving and rebuilding their societies should be embraced (Crisis Group, 2020). This has been the recent experience in Yemen (UK Government, 2020).

Building legitimacy is particularly important because governments need to rely on the voluntary compliance of citizens to public health interventions to contain the virus effectively. Sierra Leone was able to reverse its initially unsuccessful effort to counter the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak by working through locally trusted institutions to elicit citizen compliance with health-related interventions.

- Good governance and debt relief

Fostering legitimacy would not only help contain conflict, it could also help mitigate debt vulnerabilities in the continent. Legitimate governments tend to have better incentives to match the time inconsistencies between short and long-term debt management goals (Herman, 2016).

Daron Acemoglu’s recent proposal is particularly relevant for conflict-affected and fragile countries in Africa (Acemoglu, 2020). He urges that external debt for countries that borrowed under legitimate and democratic governments could be restructured on generous terms. The same would apply to long-term foreign direct investors because these forms of lending are less likely to end up in autocrats’ or rebels’ pockets. Ordinary citizens should not suffer the consequences of deals made between creditors and autocrats that are not legitimate in the eyes of the citizens.

Accordingly, help for countries with debt problems should be framed in a way that discriminates between legitimate and illegitimate autocratic governments. Thus, in a context where creditors (multilateral and bilateral lenders) link lending and debt conditionalities to good governance, autocratic governments have an incentive to become more “democratic” because they need debt financing to navigate the crisis period.

Conclusion: Crisis contingency planning

Africa’s toxic cocktail reinforces the case for including state-contingent clauses in new debt contracts, stipulating the actions to be taken by creditors and sovereigns when a crisis occurs (The Conversation, 2020). With these clauses in place, when major conflict events (civil wars, major riots, protests), an epidemic, or pandemic occurs, the crisis-contingent clauses can automatically kick-in. This would allow countries to immediately focus on dealing with the crises at hand, while debt servicing and restructuring issues are postponed until when recovery is in sight. This model is already being successfully used in Haiti in relation to the occurrence of natural disasters (World Bank, 2010).

Going forward, fungibility of debt financing should be restricted to pre-agreed development projects, especially for fragile countries. This would help minimise leakages of debt financing into less productive investments in defence and armament, helping countries focus on high-yielding social and economic investments.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.