COVID-19 and the willingness to vaccinate: Evidence from India

Vaccination is one of the success stories in modern day medicine and seen by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a key element of the response to the current pandemic. While billions are poured into a vaccine’s development and tackling supply difficulties, policymakers should prepare for the next challenges: compliance and ability to pay.

One of the most, if not the most, at-risk groups of COVID-19 is the urban poor, living in overcrowded conditions with very limited access to public health infrastructure. One billion people live in such informal settlements, more than half of these are in Asia and almost a fifth in India. In June 2020, we surveyed 4,000 slum dwellers in two Indian cities in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow and Kanpur. The heightened risk of this population is clearly visible with 2% of households reporting that someone in their household tested positive for COVID-19, compared to a worldwide infection rate of 0.2%.

Higher willingness to vaccinate among slum dwellers

Our data reveals that, contrary to advanced economies, stated willingness to vaccinate is high among this slum dweller population. Of those surveyed, 95% would like to get the vaccine for COVID-19, while willingness in seven European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) was at only 74% in April 2020, despite most of these countries experiencing their first peak of cases at this time.

Moreover, willingness to vaccinate has decreased significantly over time in Europe, evidenced by 45% of Germans stating that they would refuse to vaccinate following the easing of lockdown restrictions. On the contrary, we find no correlation in our data between exposure to confirmed COVID-19 infections in the household and willingness to vaccinate. This suggests that compliance might be high even after flattening of the curve in India.

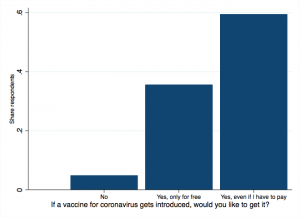

Importantly though, in addition to 5% of the population not willing to get vaccinated, 36% stated that they would only get vaccinated if they did not have to pay for it. This information is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Willingness to get vaccinated if COVID-19 vaccine is introduced

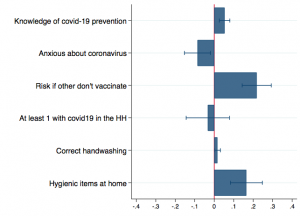

If payment was required, it is not only those with little means to pay that would not get vaccinated. They are also the ones less likely to be able to adhere to COVID-19 guidance. We find that even after accounting for poverty status, stated willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccination is positively associated with better knowledge of COVID-19 prevention behaviour and proper hand-washing hygiene, greater availability of hygienic items at home, and higher awareness of risk if others do not vaccinate[1]. This is highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Relationship between willingness to pay and other factors

Note: Estimates from a linear regression model with slum fixed effects and controlling for an indicator of strong dwelling and the respondent’s age, sex, relation to household head, and caste.

We also find that those more anxious about the virus, are less willing to pay for a vaccine. This could be driven by fear of side effects, a major factor for resistance to vaccination against COVID-19 in advanced economies. Extreme anxiety can also generate a loss in hope on the effectiveness of any vaccination to come.

Health officials can play a crucial role in information dissemination

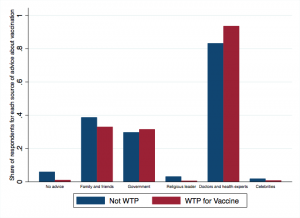

Our data suggest that doctors and health officials can play an important role in disseminating accurate information related to COVID-19 and its potential vaccination. 90% of slum dwellers report that they would turn to these health specialists for advice in case a vaccine against COVID-19 is introduced. This percentage is even higher among those respondents that also report a willingness to pay for any COVID-19 vaccine.

On the contrary, a larger percentage of respondents reporting that they would not look for advice or would get advice from family and friends about the vaccine, are those not willing to pay.

Figure 3: Seeking advice

Policy implications

The implications of our results for policymaking are twofold:

- Any future COVID-19 vaccine should not only be sold at cost by the pharmaceutical corporations developing it but also be subsidised, or made available for free to the people. When the social benefits are larger than the private willingness, or ability, to pay, there is scope for public intervention to distribute subsidised or even free vaccines. Evidence suggests that one-off subsidies for preventive health goods could boost long-run adoption (even if having to pay in the future), through learning. Given the logistical constraints to expand coverage rapidly and the less than universal willingness to pay for the vaccine, governments should consider targeting free vaccines to vulnerable people and those in high-risk jobs.

- Spreading accurate information about how to prevent COVID-19 is key for vaccine compliance. Misperceptions of ways to prevent COVID-19 can generate a false feeling of safety and reduce the willingness to get vaccinated. Doctors and health experts play an important role in distributing accurate information about any potential vaccine. Our data suggests that social networks and government officials might be useful in reaching those with low willingness to vaccinate, or low willingness to pay for the vaccine. There is evidence that gossip from influential individuals and celebrities endorsing vaccination on social media, improves knowledge about vaccination and compliance.

Editor’s note: This article is published in collaboration with Ideas for India.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.

[1] Agrees with the statement “if my neighbour refuses to get vaccinated for coronavirus, he/she will put at risk my health”.