Lockdown without borders: Regional integration and the AfCFTA can drive Africa’s COVID-19 response

In Africa, regional integration has long been viewed as a catalyst for long-term prosperity. With COVID-19 placing severe strain on economies across the continent, regional coordination can be an effective tool to manage the response and promote post-pandemic recovery. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), whilst delayed, has created a platform and dialogue to support this. In a world defined by national borders, anti-globalisation and the reshoring of global supply chains, the continent will become more interdependent than ever.

Barriers are rising. Travel and trade have been forcefully curtailed in a bid to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the World Trade Organisation expects worldwide goods trade to plunge between 13 and 32%. Across the world, national governments have been quick to stop essential supplies from leaving the country, whilst doing everything they can to lure those same goods in from elsewhere. Uncoordinated national action is inefficient and risks smaller countries being muscled out of global markets.

Focusing on Africa

The IMF expects economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa to contract by 1.6%, their worst reading on record. It comes as a result of domestic lockdown measures, weak global growth, and a sharp decline in commodity prices. Africa has deep trade linkages with Europe, China, and the US, with these partners accounting for over half of Africa’s total exports and imports (UNECA 2020). As those economies wither under COVID-19, demand for exports drops and supply chains become disrupted. Exporting firms will be the first to suffer and their decline will ripple across domestic production networks, particularly in industries such as manufacturing, transport, and trade (Huneeus 2018). Firms reliant on imports for production may also come under stress if those inputs become unavailable or more expensive. Resource-intensive countries, such as Nigeria and Zambia, will be hit hard by a fall in commodity prices and the subsequent deterioration in revenue.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitates a response to both the health and economic crises it has generated. International trade plays a fundamental role to these responses in Africa. On the health side, African countries rely heavily on importing the medical and pharmaceutical products required to test, protect, and treat COVID-19 (UNECA 2020). Most African countries are also net food importers, requiring access to global markets to feed their populations (FAO 2019). On the economic side, with so many livelihoods dependent on international trade, maintaining as much of this activity as possible will help to protect incomes.

Goods in, but not out

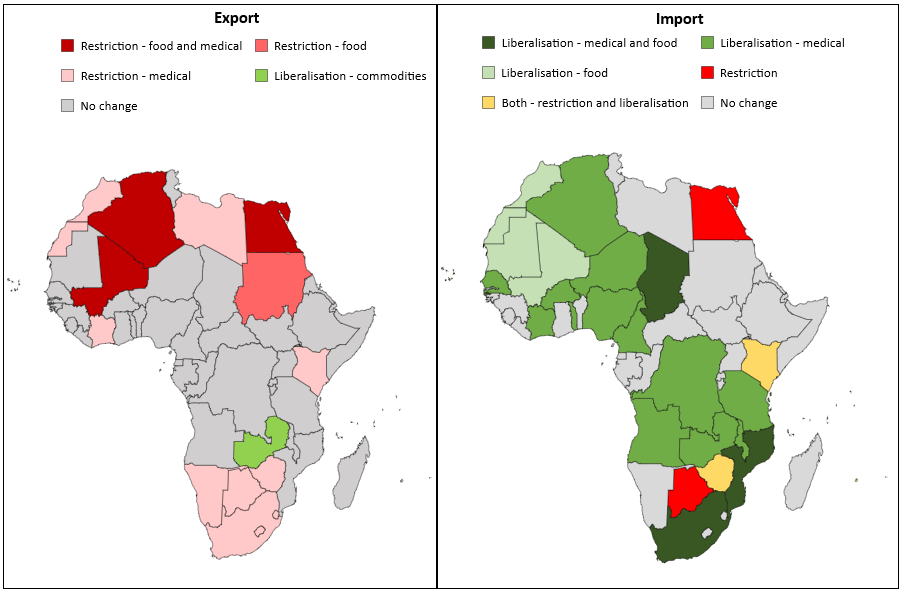

Across the world, national governments have quickly placed restrictions and prohibitions on exports. As of the 10th June 2020, 33 African countries had introduced some sort of new trade policy to combat the fallout of COVID-19, as shown in figure 1 below. On the export side, 13 countries have restricted the export of medical supplies, including items such as face masks, hand sanitizer, and personal protective equipment (PPE). Another four countries have restricted food exports. Zambia has lowered tariffs on the export of precious metals and crocodile skins to encourage economic activity and provide some relief to businesses.

On the import side, 20 countries have reduced tariffs on medical supplies, the same products being prevented from export, and seven countries have relaxed tariffs for food products. Some countries have combined this with restricting imports. For example, Mauritius has prohibited animal imports from countries suffering from a high prevalence of COVID-19 and Zimbabwe has restricted textile imports. Kenya has restricted textile imports but lowered VAT on all other imports, which is seemingly the only example of a broad-based policy change. In terms of restrictions, Botswana has placed controls on tobacco imports and Egypt has restricted agricultural imports from China.

Figure 1: Many African countries have restricted exports and liberalised imports in response to COVID-19

Source: Data source: International Trade Centre (2020)

Source: Data source: International Trade Centre (2020)

Given the reliance Africa has on importing food and medical supplies, restricting the export and liberalising the import of these goods may be beneficial in the short-term. Worryingly, there have been reports of essential medical supplies destined for the developing world being seized at transit hubs. It is no surprise that domestic production is being ramped up across the continent. South Africa has issued a tender for the manufacture of ventilators and Kenya has pivoted the textile industry towards face masks and PPE (Brookings 2020). There is little downside to strengthening local manufacturing capacity and diversifying supply chains, particularly for essential goods.

However, this response has not been coordinated or comprehensive across the continent. Although implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has been delayed, that should not allow national governments to turn inwards. If there are to be shortages of essential goods, smaller countries may find it difficult to acquire such items, whether through a lack of domestic productive capacity or increasingly inaccessible global markets. Even for larger countries, developing strong regional linkages would help to attract investment, develop infrastructure, and create economies of scale, ultimately benefiting the post-pandemic recovery.

Africa first

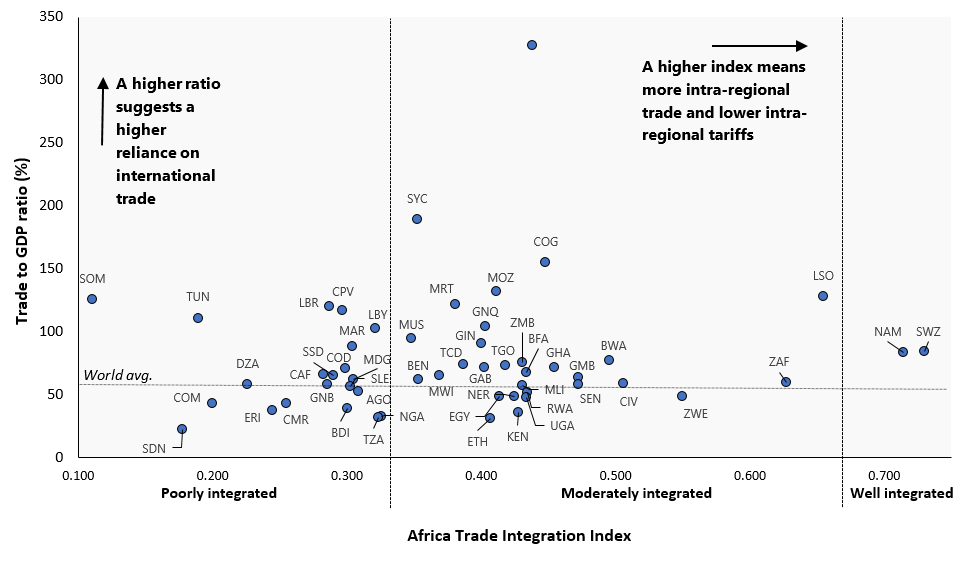

Long before COVID-19, regional integration has been seen as a key driver of economic development in Africa. Currently, the continent is fragmented, dogged by poor infrastructure, high transaction costs, and tariffs. Infra-African trade is low and regional value chains are underdeveloped, as highlighted in figure 2. Building these chains through the gains of economies of scale and division of labour will help develop the production of goods with higher value-added and drive industrialisation. This will also be the fastest way that Africa can capture larger portions of illustrious global value chains where its participation, whilst higher than 1990, remains low (De Melo and Twum 2020).

Figure 2: African economies are reliant on international trade but for most, not much of that is with their neighbours.

Data source: Africa Regional Integration Index (2020), World Bank (2020)

Data source: Africa Regional Integration Index (2020), World Bank (2020)

The AfCFTA goes a long way in supporting regional integration by dismantling tariff and non-tariff barriers. It has the potential to significantly boost intra-African trade and GDP. Admittedly, there remains unanswered questions about the costs of trade integration, particularly how it may unevenly affect countries or have adverse consequences on income distribution. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, there must be complementary investment in infrastructure and productive capacity to maximise its benefits.

Delaying the AfCFTA is unfortunate

The delayed implementation of the AfCFTA is unfortunate, and it must be remembered that any movement away from integration in the short-term will inevitably make it harder in the future. Managing COVID-19 and supporting post-pandemic recovery can be much smoother if regional coordination is encouraged. Multilateral actors, the African Union, and the AfCFTA secretariat, must remain engaged with member states and regional economic communities to support and assist with this response. Regional economic communities, particularly the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and East African Development Community (EADC), are well placed to pool efforts in procurement and production in the short-term, report on the availability of supplies, and commit to export agreements with each other (UNECA 2020). The political capital and dialogue created by the agreement must be utilised to ensure protectionist policies are temporary. Creating these stronger regional linkages today will alleviate the current crisis and ease the implementation of the AfCFTA in the future.

Concluding remarks: African governments must work together

The timing of the COVID-19 pandemic has come at an important juncture in international trade. Anti-globalisation was already on the agenda, illustrated by the US-China trade war and the UK’s decision to leave the European Union. In the post-pandemic world, the rise of anti-globalisation and reshoring of production will threaten the interconnectedness of the global economy. Whilst unlikely to be reversed completely, it will become increasingly difficult for Africa to gain a foothold in global value chains. African governments and regional trade blocks must work together to drive inclusive growth and productive investment to create an African market filled with African producers and African consumers.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.