Responding to COVID-19 in fragile states: The case of Sierra Leone

Lessons from the Ebola outbreak supported a prompt response. A financing gap undermines efforts, requiring adaptive coordination among stakeholders.

Sierra Leone was the last country in the Mano River Union (MRU) basin to record a positive case of the COVID-19 virus, on 31 March 2020. As of 12 May, the country now has 338 (cumulative) confirmed cases, 72 recoveries, and 19 deaths (Worldometer, 2020). It is important to note that the figures are those officially reported and based on tests done at COVID-19 related test facilities established by the government.

Prior to the index case, the country implemented strategies that are largely regarded as proactive and innovative to prevent the pandemic from entering the country. This could be attributed to lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic in 2014/2015. These include:

- Robust screening at the airport for all passengers coming into the country.

- Quarantining of travellers from countries regarded as epicentres.

- Engagement with local leaders to enable the use of local structures for sensitisation purposes.

- Promoting the use of handwashing facilities (veronica buckets and soap) in public places, including offices.

Pre-existing health system challenges

With an average life expectancy of 54 years, an infant mortality rate of 92 per 1,000 live births, and a maternal mortality rate of 156 per 1,000 deliveries, Sierra Leone has some of the worst health indices in the world. The country lacks basic health infrastructure to effectively prevent and manage routine illnesses.

Funding from the government to the health sector remains a major challenge. Funds are not only inadequate and untimely, but also unreliable, thereby routinely impeding planning and implementation. Per capita health expenditure for 2016 was less than USD 10, which was far less than the sub-Saharan African average of USD 27 and the average for fragile states of USD 20 (World Bank, 2020).

There are also problems with the quantity of skilled personnel, particularly in public health facilities. With a total population of over seven million people, the country has less than 400 medical doctors (specialists and medical doctors combined) in public facilities. Over 70% of these are medical officers and general clinicians. Additionally, deployment of these doctors is skewed towards the cities and other affluent districts leaving the hard-to-reach areas underserved.

Inadequate social protection amid extreme poverty and vulnerability

With a poverty rate of 56.8% and over 70% of the working population employed in the informal sector (Sierra Leone Statistics, 2018), there is a desperate need for social protection support, especially during a pandemic such as COVID-19. In Sierra Leone, social protection support for vulnerable groups is very minimal.

Prior to the outbreak, the total number of persons benefiting from any form of social protection support from government was less than 10,000, even though the recent Sierra Leone Integrated Household Survey (SLIHS, 2018) suggests that persons living in extreme poverty is about 16% of the country’s population (over one million persons). Additionally, the support that is delivered is not only inadequate and untimely, but also unpredictable.

Some of the measures implemented to prevent and contain the spread of the pandemic include restrictions to inter-district movement, a night curfew (9 pm to 6 am), and a three-day lockdown, among others. These measures tend to increase the number of vulnerable persons and move more people below the poverty threshold.

During the restrictions, the government and many charitable groups distributed food items to slum areas and vulnerable groups. This was neither systematic nor comprehensive – considering the estimated over one million people living in extreme poverty (Ibid). There is no comprehensive database on the number of vulnerable people living in Sierra Leone.

In addition, global estimates (using the most recent data) suggest that COVID-19 will push between 40 million and 60 million people into extreme poverty. This means there will be more new poor in Sierra Leone. It is important to identify, target, and support them in a timely manner.

Sierra Leone’s COVID-19 response: Coordination and collaboration

During Sierra Leone’s prevention phase, efforts were made to reactivate the community sensitisation structures used during the Ebola outbreak. Officials from the Ministry of Health and Sanitation visited and informed several community leaders nationwide. While this effort was commendable, it was not followed through. At best, subsequent efforts were not inclusive, as other major stakeholders – such as opposition political parties, parliamentarians, and local councillors (especially those from opposition areas) - were not adequately engaged.

Initial response and coordination efforts were led by the Ministry of Health and Sanitation. This effort was highly commended as almost all stakeholders, including the leadership of political parties, were engaged. Perhaps most importantly, the leadership of the Ebola Response team was invited and participated. Learning from the Ebola experience, a dedicated structure (Emergency Operation Centre/EOC) was constituted to coordinate all stakeholders.

The initially applauded inclusive approach, which included all political persuasions, has been diluted by conflicting accusations between Government and the main opposition political party. The arrest and detention of the head of the National Ebola Response programme on allegations of attempted treason has resulted in opposition party members no longer participating in the EOC.

Economic impacts

- An already compromised economy

With a fluctuating gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate, high inflation rate (14%), and depreciation of the domestic currency against major international currencies, the Sierra Leone economy was already struggling to recover from the multiple shocks of the Ebola outbreak (2014 to 2015), fall in commodity prices, and the mudslide of September 2016, prior to the pandemic (Sierra Leone Ministry of Finance, 2019).

- Trade and food security

The pandemic has led to the disruption of supply chains and a decline in export and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows, tourism, and business expenditure. With prevention measures being implemented and with the commencement of the planting season (namely rice – the country’s staple food), agricultural production may contract, which may undermine government food security efforts.

- The informal sector

While some efforts are planned to cushion the effect of the pandemic on major businesses through the provision of credit facilities at reduced interest rates, it is not clear how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will be supported. These businesses are mostly in the informal sector, employ over 70% of the country’s population, and will perhaps be the hardest hit by the pandemic. Granted, development partners and government have recognised the relevance of the sector and have touted their desire to support it. However, to date, the strategy for how these businesses will be identified and targeted has not been announced.

The Quick Action Economic Response Programme: A financing gap

Based on initial simulations, the government has revised the projected GDP growth figures and revenue loss for 2020 according to potential outcomes (see the COVID-19 Quick Action Economic Response Programme/QAERP):

- Scenario 1 (best case): There are numerous positive cases and fatalities in trading partner and donor countries, but no positive cases in Sierra Leone. Under this scenario, projected GDP growth rate is revised from 4.2% to 3.8% and a revenue loss of 9%.

- Scenario 2 (worst case): Positive cases in Sierra Leone result in short term nationwide movement restrictions. Here, the projected GDP growth rate is revised from 4.2% to 2.2% and a revenue loss of 15%.

- Scenario 3: In addition to continued disruptions globally, positive cases emerge domestically, the country’s health system becomes overwhelmed, and more significant 'lockdown' measures are introduced for a more extended period. Under this scenario, projected GDP growth rate is revised from 4.2% to negative.

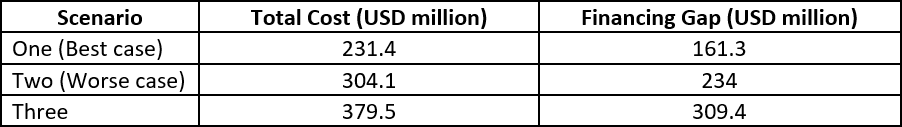

The QAERP’s primary objective is to be able to respond to the health crisis as well as mitigate the socio-economic challenges that will emerge as a result of the pandemic. The programme costs are as follows:

Table 2: Estimated cost and financing gap to support the Government of Sierra Leone’s Quick Action Economic Response Programme (QAERP)

Source: Government of Sierra Leone COVID-19 Quick Action Economic Response Programme (QAERP), 2020.

Source: Government of Sierra Leone COVID-19 Quick Action Economic Response Programme (QAERP), 2020.

Clearly, for all the scenarios, there is a huge financing gap. The country is already struggling with a huge debt burden (both foreign and domestic). If the option of financing the gap is through additional borrowing, the impact will be catastrophic. Recognising this, development partners have announced debt relief, and in some cases moratorium, as well as concessionary loans and grants to help provide the fiscal space needed to support the government effort.

Recommendations

- Awareness and prevention

While the government continues to introduce measures to contain and prevent the spread of the pandemic, recent political tensions (particularly between the government and the main opposition) has undermined the response effort. Social mobilisation efforts are also affected as the media (particularly social media) is awash with inciting political messages, instead of COVID-19 prevention and awareness messages. Therefore, conscious effort should be made to de-escalate the political tension and refocus everyone’s effort on the response.

- Inclusive stakeholder coordination

It goes without saying that a coordinated and inclusive approach will help boost social mobilisation efforts and help contain the pandemic. Therefore, it is important for the government to review its coordination strategy to include all stakeholders including opposition parties. The lessons from the Ebola crisis clearly suggest that there was significant acceptance of the social mobilisation messages when political parties and community leaders joined forces with the government.

- An adaptive and long-term response

Finally, while the swift attempt by government to prepare a response programme is highly commendable, given the evolving nature of the pandemic, backed by the additional data now available, it is important for the government to review QAERP to not only reflect the new realities, but the underlying challenges the country was facing even before the crisis.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.