Sierra Leone locked down early to contain COVID-19, but at a high price

Sierra Leone locked down early and appears to have COVID-19 under control. But the country has paid a very high economic price, with the vast majority of people missing meals or eating less. Researchers warn that if the virus begins to spread again, these sacrifices may be hard to justify and replicate.

In the fight against COVID-19, we are in the same storm but in different boats. The patterns of the virus’s spread, the policy instruments available to governments, and the economic consequences of the disease all differ markedly between high-income and developing countries. Right or wrong, however, government responses—in the form of border closures, lockdowns, and distancing requirements—have been remarkably uniform.

Take sub-Saharan Africa. Just as in Europe, in the first weeks of the pandemic, many countries reacted quickly to impose restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19—even before they had confirmed any cases or deaths. One was Sierra Leone, which recently experienced another major health crisis with the outbreak of Ebola a few years ago.

In Sierra Leone, where we are collecting data in collaboration with the International Growth Centre (IGC) at LSE, Wageningen, and Yale University, we notice three patterns that also appear in other sub-Saharan African countries.

- First, in terms of death rates, there was a delayed onset and subsequent curve flattening;

- Second, there were rapid government and societal responses;

- and third, these responses have taken a heavy economic toll across broad sections of society.

We document these trends and point towards the mismatch between the benefits of the early lockdowns and the heavy economic costs shouldered by the population. We argue the priority now is to develop economic and health models tailored to developing countries like Sierra Leone.

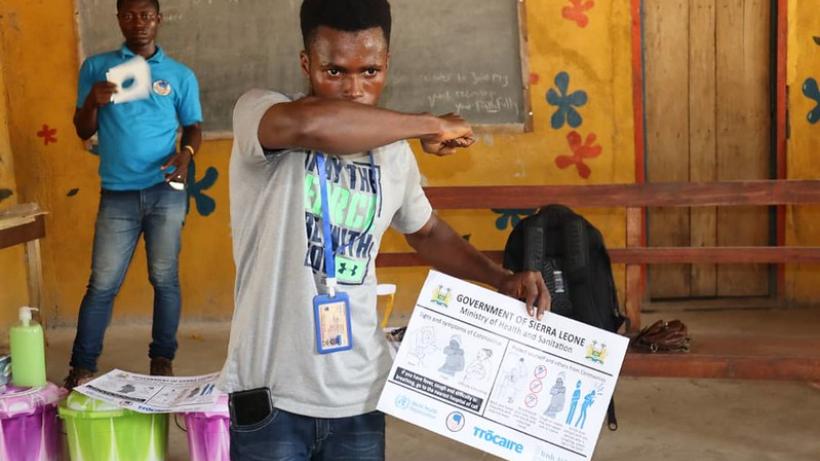

Mohamed Kanu, SEND-SL Project Officer, demonstrates COVID-19 preventive measures to participants at Morabie Community Ward, Sierra Leone. Photo: Trocaire via a CC BY 2.0 licence

Death rates across sub-Saharan Africa

The good news is that, comparatively, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced a slow growth in reported deaths from COVID-19 over time. The reasons for this remain puzzling. Part of the answer might be found in the early policies to control the spread of the disease. Other explanations emphasise Africa’s younger populations and, in some accounts, populations’ possible contact with other types of coronaviruses – or it could very well be because of lower rates of testing.

A significant concern, however, is that even though the growth in death rates in the region has flattened, it remains positive and sustained. This could suggest much greater burdens in the near future, as deaths accumulate over time.

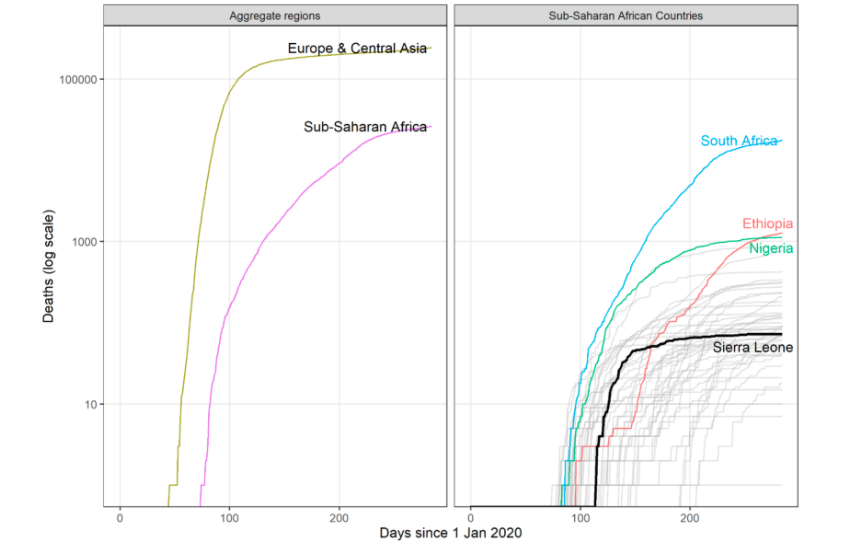

A more complex outlook emerges when looking at the national trends in death rates. As the graph below illustrates, the progression of COVID-19 has been wildly different across countries in sub-Saharan Africa. These differences between regions and countries are the first indication of the importance of national contexts when crafting responses to the pandemic.

Figure 1: COVID-19 deaths in 2020 in Africa and Europe, and in four African countries

Rapid policy and social response

Many African countries acted fast by closing borders, imposing quarantines, and, in some cases, implementing extensive testing. Côte d’Ivoire, for instance, carried out surveillance at airports as early as 2 January. Uganda implemented extensive testing of truck drivers entering the country and carried out random testing long before there were any known COVID-19 deaths.

Sierra Leone, too, took quick action in an effort to contain the spread of COVID-19 and reduce the number of deaths. The government declared a state of emergency in March before any cases were confirmed in the country and announced a three-day lockdown when the second case was confirmed at the beginning of April. Another lockdown was declared in early May. In addition, the government restricted between-district travel between 11 April-23 June, and closed the airport for four months between March-July.

Reactions by Sierra Leoneans were also rapid. In our survey, we notice high levels of (self-reported) compliance with many preventive measures. In early June, 58% of people reported wearing masks, 92% reported avoiding shaking hands, and 86% of respondents increased the number of times they washed their hands—despite limited access to clean water. This prompt response from both government and the population likely reflects learning from recent health crises, specifically Sierra Leone’s recent experiences with Ebola.

Drastic economic consequences

The relative public health success in Sierra Leone notwithstanding, evidence points to an impending economic crisis. Precautionary measures have imposed major costs on households. According to our data, income dropped for 57% of households while food prices rose by up to 16%. By April, 87% of rural households in Sierra Leone were forced to miss meals, reduce portion sizes, or consume less preferred food to cope with the crisis.

Additionally, there are other risks related to preventative measures, such as reduced visits to clinics. While we do not find strong evidence of this in our data (only 2% of the respondents say they have skipped a visit to a health centre since March), some media accounts reflect concerns about fewer visits to health centres for other endemic diseases like malaria.

To temper the economic crisis, the government has been working to develop their Quick Action Economic Response Programme (QAERP). The program is projected to cost $166 million, with up to $6 million delivered as cash transfers. In per capita terms, this represents less than $1 per person.

Even when considering the best-case scenario, the country’s economic responses will be very limited. Indeed, our survey suggests that only 36% of the respondents are currently receiving aid from the government. In contrast, 80% of those surveyed reported asking for help from relatives or friends for food at least once a week. It is likely that official forms of social assistance are not reaching the most vulnerable.

Improving COVID-19 responses

Sierra Leone’s government engaged seriously with the threat of COVID-19, and it is quite possible these actions were needed to yield the low mortality rates. What is not yet clear is if the strategies were optimal, given the possibly large economic consequences. While very similar containment policies were put in place in countries around the world, the economic and human costs are higher for developing countries. And yet, we have found no public health or economic model that provides credible and tailored answers to countries like Sierra Leone.

Interviews with government officials in Sierra Leone suggest that they now broadly consider the worst to be over and are more focused on the critical task of economic recovery than on prevention of future COVID-19 spread. Hopefully, the government’s diagnosis is correct. But if COVID-19 begins to spread again, as it has in other regions of the world, the kinds of sacrifices made in Sierra Leone as part of this early response may be difficult to justify or replicate. In that case, policy responses will need to be better tailored to country-specific conditions and be based on models that combine basic research in medicine and social science with up-to-date information on the local situation. This collaborative work should now be a priority.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on the LSE blog

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.