Torn safety nets: How COVID-19 has exposed huge inequalities in global education

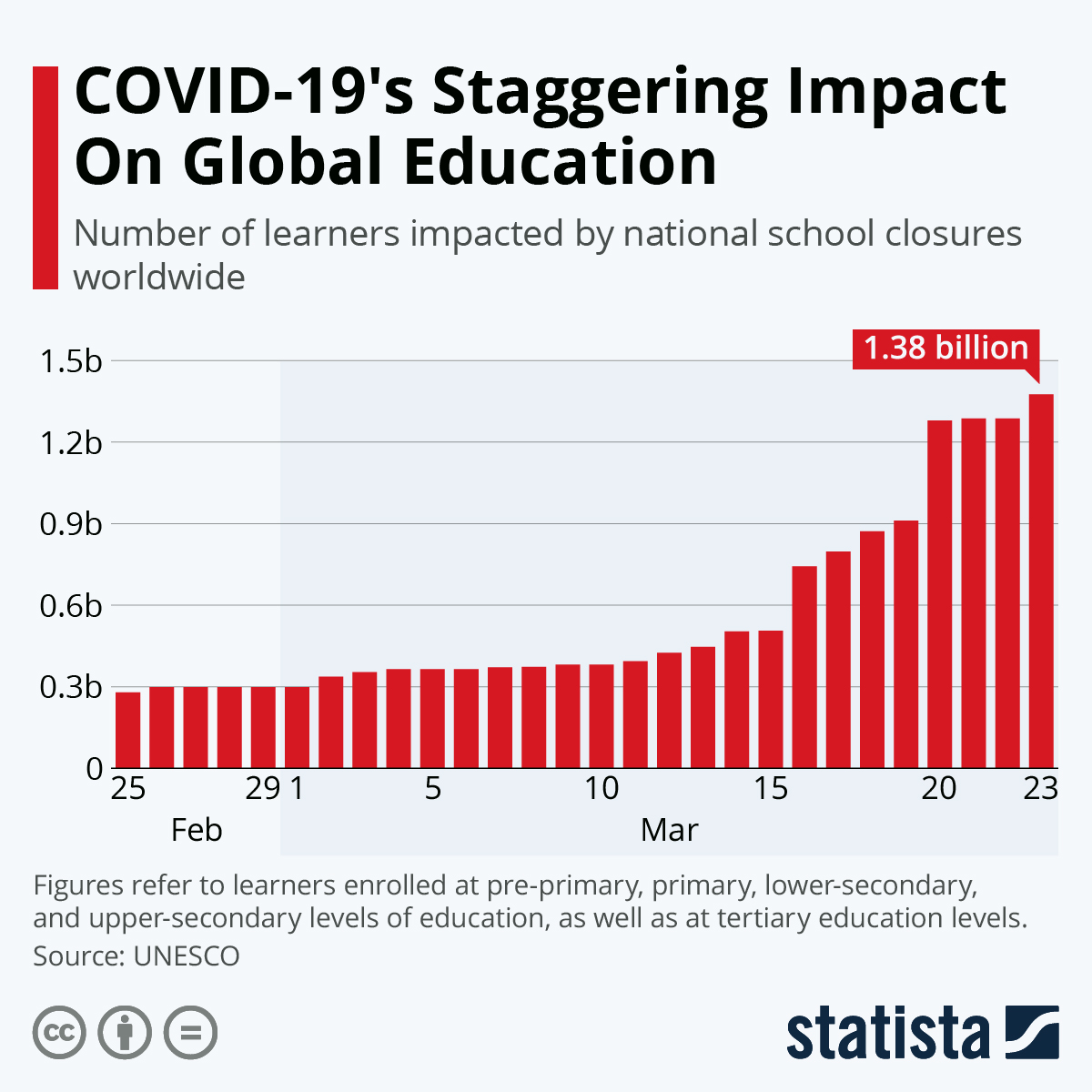

In 2018, 258 million children of primary and secondary school age were out of school. Now, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, 1.2 billion children find themselves out of school, at least physically.

In both the developed and developing worlds, schools have been more than just places of learning; policy designs have moulded them into safety nets for children. However, the present pandemic has torn those structures apart and revealed gaping inequities. And now, with the need to maintain physical distancing, schools are shut in 146 countries. For many children, this vital safety net has disappeared.

Learning losses

The most obvious impact of school closures has been on student learning. Unfortunately, even before this public health crisis, the developing world was already experiencing a learning crisis. Fifty-three percent of children in low- and middle- income countries cannot read and understand a basic text at age 10. Now, as learning switches to remote platforms, this crisis is not only likely to exacerbate but also deepen along the divides between those advantaged to access them and those disadvantaged who cannot.

About 65% of lower-middle income countries and less than 25% of low income countries have been able to set up remote learning platforms. Moreover, only 36% of residents of lower-middle income countries have access to the internet which raises further concerns regarding the reach of remote learning. Even among those who are able to access these platforms, we know little about their efficacy or ability to cater to the needs of differently-abled learners, especially in these strained times.

Missed midday meals

In 2019, the World Food Programme estimated that at least 310 million children in low- and middle- income countries were fed at school. Midday meals have boosted enrollment (especially among girls), improved nutritional profiles of children, and alleviated the financial strain on poor families. With the schools now closed and an increased risks of food deprivation and disrupted supply chains in the developing world, these children now face increased malnourishment and hunger. Along with the midday meals, children are also missing out on the company of friends, which is essential for their mental wellbeing.

Pressures of parenting

During this time, parents have invariably become the primary responders to the needs of their children. But how well-equipped are they? At best, they are juggling full-time jobs and homeschooling their children. But mostly, they are struggling to make ends meet. Large shares of the population in low and lower-middle income countries are employed in the informal sector and they are now estimated to have seen a reduction of 82% decline in earnings in the first month of the crisis alone. With little or no safety nets, they have had to make heart-wrenching journeys from cities to their rural homes, often with their children in tow. These parents have more pressing concerns than the continuation of their children’s education and understandably so.

Risks of reopening

Even though some countries have begun to reopen schools, this unfortunately may not be the best way to respond to the needs of these children. In reopening schools, there is the risk of breaking the safe bounds of physical distancing and increasing the transmission of infection. While the disease has been known to mostly target the older demographic, the evidence of children's immunity to it is unclear.

The pandemic is accelerating in the developing world and there are reasons to be worried that children in these countries may be more susceptible to this illness owing to their potentially lower levels of immunity that comes with higher prevalence of malnutrition. And even if children were safe from contracting the disease themselves, there is still the risk of them transmitting it to their teachers, other school staff, and members of their own family, some of whom might even be elderly, as multi-generational households are fairly common in developing countries.

Short-term solutions

Even though traditional learning in school has been disrupted, it is still essential for learning to continue. Students in developing countries are prone to dropping out and extended periods of school closures can cause some of them to fall through the cracks. Remote learning, however effective, allows children to keep learning, especially when these online platforms are free to access. Some governments have also found ways to carry on providing midday meals to children. Social protection should also be extended to vulnerable populations as a way to ensure that parents are able to support their children.

Continuing consequences

The consequences of a crisis continue to unfold long after it is passed. Authorities must take strong efforts to re-enroll children and be vigilant to dropout rates once schools reopen. The economy will have undoubtedly taken a hit in the wake of this crisis and many households will have receded further into poverty. This can also pull children out of schools and push them into child labour. Those who return to school, meanwhile, may have struggled to keep up with coursework.

The demotivation and stigma of falling behind their peers can also lead to them dropping out of school. This makes the provision of remedial classes for children to reach their expected basic levels of learning essential. Governments must also continue to financially assist parents as they try to restart their careers and look after their children. They must also prepare for the possibility that there will be a second wave of the pandemic.

Crises such as this can widen the opportunity gaps that perpetuate intergenerational cycles of poverty and low human capital creation. The educational inequality borne of this crisis will continue to have an impact on income inequality. It is therefore even more essential for us to re-structure our systems of education so that they become more resilient and sensitive to the diverse needs of children all across the world.

Editor’s note: This article was first published in the World Economic Forum.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.