Tourism and COVID-19 in Zambia

COVID-19 is a real threat to Zambia’s tourism sector and there is a high risk that many firms will shut down and disappear, undermining any ultimate economic recovery when international travel resumes.

The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) has warned that the COVID-19 pandemic could cut 50 million jobs worldwide in the travel and tourism industry. The industry, which currently accounts for close to 10% of global GDP, is expected to contract by 20% to 30% in 2020.

Zambia’s travel and tourism industry, which has shown signs of healthy growth in recent years, would be impacted significantly by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the industry contributed 7% of GDP (USD 1,701 million) and 7.2% of total employment (469 thousand jobs). International visitors spent USD 849 million, representing 10% of Zambia’s total exports.

This blog post synthesises information drawn from structured interviews administered by the International Growth Centre (IGC) in Zambia.

Zambia the “add-on” destination

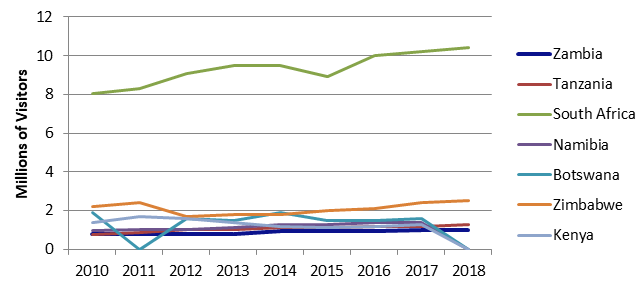

Zambia is an underdog within the Regional Tourism Organisation of Southern Africa (RETOSA). Though Zambia has seen a sustained increase in the number of international visitors recently (Figure 1), it is dwarfed by South Africa and still lags well behind Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana. Direct flights to Zambia from Europe and Asia are limited, making Zambia an “add on” destination for international travellers visiting neighbouring countries like South Africa and Botswana.

Figure 1: International tourism arrivals

Source: Constructed by author using data from WB-WDI

Source: Constructed by author using data from WB-WDI

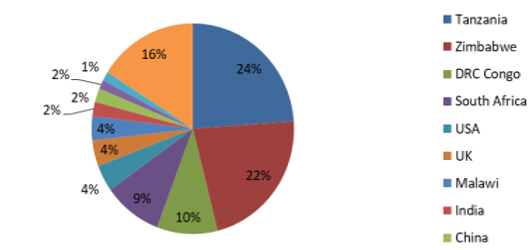

Figure 2: Main sources of arrivals (all purposes)

Source: Adapted from CBI Netherland Report (2018), pg. 10

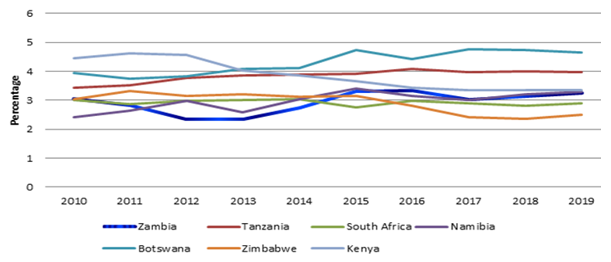

Figure 2 indicates that Zambia’s top-20 international markets accounted for 84% of arrivals for all purposes in 2016 and that four African markets, namely Tanzania (24%), Zimbabwe (22%), Democratic Republic of Congo (10%) and South Africa (9%), accounted for two-thirds of international arrivals. High value tourism from the UK and US are only 8% of total arrivals. In terms of contribution to GDP (Figure 3), the tourism sub-sector contributes approximately 3% to Zambia’s GDP, below the shares in Botswana and Tanzania.

Figure 3: Contribution of tourism to GDP

Source: Constructed by author using data from UNTWO

Source: Constructed by author using data from UNTWO

Detrimental effects on the economy

Though Zambia has not closed its borders, the number of international visitors has declined sharply. The first three months of 2020 saw a drop of over 14000 international visitors. A snap poll of members of the Eco-Tourism Association of Zambia (ETAZ) suggests that Zambia’s safari tourism and allied sectors such as Airlines and charters would suffer a loss in income of USD100 million in 2020. Out of 257 lodges and camps, 165 have closed down already. Over 7000 jobs are likely to be lost. 165 tourism businesses in Livingstone and Zambia’s protected areas face bankruptcy. ETAZ projects recovery in revenue streams commencing only in 2021.

Environmental conservation would suffer

State resources allocated to conservation have remained low in Zambia. On average, between 2010 and 2018, 0.6% of Zambia’s national budget was allocated to environmental and wildlife conservation. Consequently, conservation activities are heavily funded by donor organisations and safari tourism firms. The loss in income of safari firms would translate into a significant drop in funding for conservation. For example, ETAZ through contribution from its members, injects over USD annually in supporting conservation activities. Similarly, the safari tourism industry in South Luangwa has established and funded a local NGO – Conservation South Luangwa – charged with broad scale anti-poaching support, and wildlife veterinary work and community development. Since 2003, eco-safari firms in Luangwa contributed USD 10 per bed/night to fund Conservation South Luangwa. The disruptive effect of COVID-19 would likely translate into increased poaching as eco-safari firms lay off workers and cut down funding of conservation activities.

What should Zambia be doing?

- Tourism: A handicapped Sector before COVID-19

From our structured interviews conducted in April 2020, administrative bottlenecks such as the cumbersome process of obtaining a license and the numerous licenses required to formerly operate in the sector has been a major constraint to the growth of the sector. Our interviews revealed that some tourism businesses require up to 58 different licenses. There are cases where a license is needed from both the local council and a central government agency for the same activity. For example, a boat license is needed from both the local council and from the department of Inland Water Ways. This heavy regulation of Zambia’s tourism sector is reflected in its relatively poor ranking in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI). In 2019, Zambia was ranked 113 out of 140 countries.

The Government should engage with the tourism sector in view of addressing some of these longstanding challenges and more recent pressing challenges. The Zambian government should consolidate its licensing process into a one-stop-shop so as to facilitate the entry of new firms into the sector especially after COVID-19.

Learning from previous pandemics

The outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in early 2003 and of the Ebola virus in West Africa in 2013 had profound negative impacts on the global travel and tourism industry. Even though the length of the COVID-19 pandemic and the recovery of global travel remains uncertain, recovery strategies from previous pandemics such as the aforementioned can help inform Zambia’s responses to COVID-19. Following the Ebola and SARS pandemics, governments were quick to negotiate the opening-up of the border and exert leverage to resume international flights once zero new infections were recorded. Zambia should, however, have a well-calculated strategy as far as re-opening its border is concerned: re-opening the border too early might be counterproductive, particularly if neighbouring countries still have increasing caseload of infections. Developing and implementing best practices at the border would also be important in regaining the trust of international visitors. In the case of Ebola and SARS, governments worked closely with international organisations and businesses to encourage their staff to return. Relaunching media campaigns aimed at tourists and the broader business community was also vital, in rebranding and improving the image of these countries.

Given that 70% of tourists visit Zambia via land border crossing points, it will be very important for Zambia to collaborate with its neighbours with the view of ensuring that border crossing points are open once the pandemic is contained, and the risk of importing infections is eliminated through appropriate quarantine measures. Salvaging the sector would require Zambia to ensure that it effectively restores its reputation as a safe destination for tourists, both from within the region and from other continents.

Labour regulations during COVID-19

In the current crisis, many employers in the private sector argue that the new employment code enacted on the 10th of May 2019, and which was due to come into force on the 10th of May 2020, inhibits the creation of jobs. There’s a substantial degree of seasonality in Zambia’s safari industry with very few visitors during the rainy season (December to April). Consequently, safari firms mostly rely on temporary labour contracted for the dry season when the industry is fully operational. The new employment code would have a particularly deleterious impact on the tourism sector, as it does not take into account the seasonal nature of employment in the safari industry. In the face of a major shock such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the code makes it extremely difficult to negotiate temporary salary and wage reductions, or even send workers on leave with a reduced paycheck.

From our structured interviews, Most firms are drawing down their reserves and coughing up additional contributions from their owners in order to sustain wage bills. These firms are likely to go out of business, compromising Zambia's ability to recover jobs and income after the pandemic. Saving jobs in the tourism sector would require the Zambian government to relax or waive some of its labour regulations temporarily, and to reconsider the long-term appropriateness of such regulations. In Namibia, the government has temporarily waived some of its labour regulations allowing hard-hit sectors such as tourism to negotiate up to 50% wage reductions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is a real threat to Zambia’s tourism sector and there is a high risk that many firms will shut down and disappear, undermining any ultimate economic recovery when international travel resumes. Zambia’s neighbours are acting swiftly and boldly to arrest the impact of COVID-19 on tourism and allied sectors. Given limited fiscal resources, it may be advisable for the policy response in Zambia to focus on effective public health measures at the borders and providing regulatory relief, particularly with regard to flexibility in the application of labour regulations and licensing requirements for firms in the tourism sector. There is urgency for the Zambian government to engage the sector in view of having a better understanding of some these pressing challenges and determining how best to address them in the short, medium and long term.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.