A window into life during COVID-19 in developing countries

Our country economists in Ghana, Mozambique, Myanmar, and South Africa share insights on how lives have changed during the pandemic.

With over 360,000 global deaths from COVID-19 as of writing, the pandemic has affected and upended daily life in almost every single country in the world, including all of the countries that IGC works in. While our in-country teams are working hard to help governments across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East respond to the economic impacts of the pandemic through new data and analysis, they are doing so without the regular physical interface with policymakers so crucial to their jobs.

We asked some of our country economists from Accra to Yangon how daily life has changed since the pandemic, their perceptions of the policy measures that government in their countries have taken so far, and their views on the future. We acknowledge these perspectives are not necessarily representative of the experiences of the average citizen in these countries, and especially not of the poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population.

Locked down

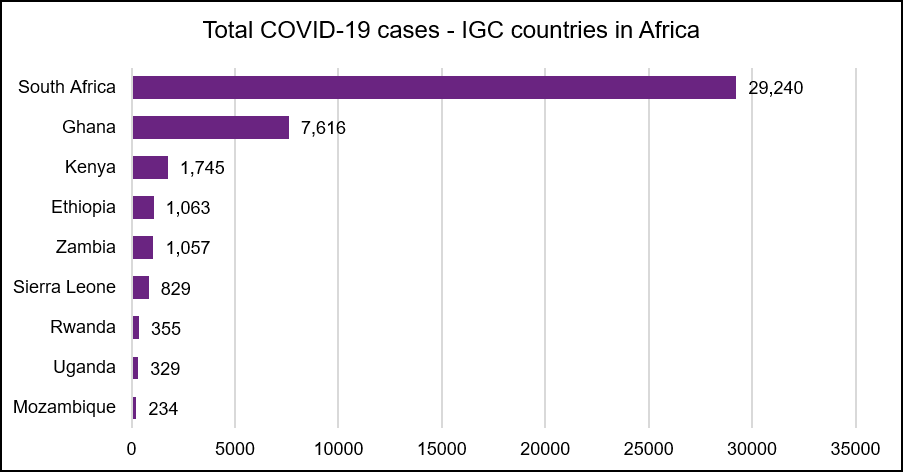

All the countries where IGC has staff have implemented some form of lockdown – with some, like India and Ghana, now easing restrictions. South Africa, the hardest hit country in sub-Saharan Africa with over 23,600 confirmed COVID-19 cases, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in the world in late March, keeping only essential places open such as groceries, pharmacies, and medical services. Interestingly, the country banned the sale of alcohol and cigarettes, which unsurprisingly led to increases in the illicit sale of these goods.

“Although I think this was an extreme approach in the context of extremely high levels of unemployment and social instability as it is (even before COVID-19 we were going through one of our worst economic slumps in history), I think it was necessary to communicate the danger of this virus and to get people to take it seriously,” said Victoria Delbridge, an IGC Cities Economist based in Cape Town.

Mozambique, with a little over 200 confirmed cases, has taken a lighter touch approach given their relatively small number of cases, but did move quickly to shut schools and ban mass gatherings. Like many other developing economies, the country’s primary concerns are COVID-19 cases overwhelming already weak health systems and lockdown measures exacerbating hunger and poverty.

“My concern is related to the possibility of worsening cases of other chronic diseases (HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis) [and] of [missed] vaccinations for children, due to the need to respond to common diseases and at the same time respond to the pandemic,” said Egas Daniel from IGC Mozambique, pointing out that the country counts only one doctor for every 20,000 people.

Recent IGC research suggests an additional 9% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa have immediately fallen into extreme poverty as a result of COVID-19, with about 65% of this increase resulting from the lockdowns themselves.

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Data accurate as of 30/05/2020. Note, IGC has staff in South Africa and Kenya but no country office.

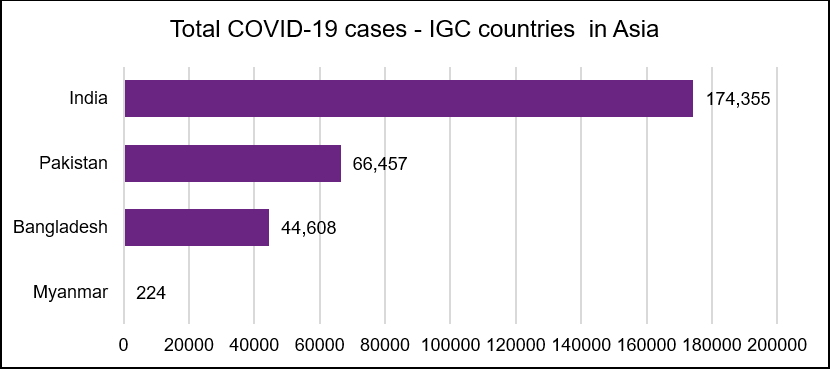

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Data accurate as of 30/05/2020. Note, IGC has staff in South Africa and Kenya but no country office.

Love thy neighbour

For the most part, the staff we interviewed said the people around them were following social distancing rules. James Dzansi, IGC Country Economist in Ghana, said in Accra, enforcement was very visible and strong public adherence to rules was “partly because of effective communication on the government side, the support from the various political parties and opinion leaders.” This observation is supported by evidence that shows leadership is crucial in getting citizens to adopt and also enforce social norms.

However, enforcing social distancing may have less benefit, and potentially harmful consequences, in dense urban areas and informal settlements where economic activity requires regular, close contact with other people.

“Social distancing and handwashing in practice is near impossible in crowded living conditions with shared ablutions. This means they are taking on the economic shock, without necessarily having the benefit of reducing the risk of contracting the virus,” said Delbridge of the situation in South Africa’s informal settlements.

While most countries are still figuring out the right balance when it comes to weighing the health and economic costs of lifting or not lifting restrictions, lockdowns have more dire and immediate consequences on livelihoods in low-income countries. Based on the little evidence that is available, IGC policy guidance for developing country policymakers supports adaptive, localised containment strategies that reduce the risk of widespread deprivation and unintended health consequences.

Trust in the government

Our interviewees perceived that people in their countries generally trusted the government in handling the pandemic, perhaps an interesting contrast to public opinion in the UK. An opinion poll in mid-May revealed that UK public approval of the government’s handling of the crisis was down to 39%.

“We all agree that we should follow government instructions to reduce the rapid spread of the virus. The only scepticism is about the actual number of cases, we believe that there are more cases out there than confirmed and reported,” said Daniel of the situation in Mozambique.

In South Africa, trust has wavered to some extent when political leaders have made decisions that caused public confusion and frustration, but the pandemic has perhaps engendered more support for the government than there was pre-pandemic.

Delbridge said “the government has shown a willingness to accept and take on feedback, and adjust their response in line with recommendations made by the best available evidence, and so I think on the whole there is trust.”

The new normal

Dzansi said the impact of COVID-19 on Ghana’s economy was his biggest concern for the future. Ghana, a commodity-dependent country and one of the first in Africa to lift its lockdown, is facing a triple threat of external revenue shortfalls from the drop in global commodity prices, domestic revenue shortfalls from the hit to the country’s businesses and employment, and challenging fiscal space with the government borrowing excessively to fight the pandemic and absorbing 100% of water and electricity bills.

In Myanmar, our country economist Siddhartha Basu expects the government to allocate more budget to healthcare and social protection in the near future. A recent IGC brief on the social protection response to COVID-19 pointed out that before COVID-19, Asia and Africa collectively spent only 3% of their GDP on social transfers, compared to 15% in advanced economies.

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Data accurate as of 30/05/2020.

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Data accurate as of 30/05/2020.

On a more positive note, our interviewees resoundingly agreed that regular handwashing will be the biggest long-term behaviour change from this pandemic.

“I think people (myself included) are now more aware of how germs are spread and the practices that we should all make a habit of in order to minimise the likelihood of this happening again, at least on this scale,” said Basu.

As countries begin the loosening of lockdowns and reopening of economies, the long-term consequences of COVID-19 will need to be dealt with by governments around the world. Emerging evidence already suggests businesses and livelihoods are being hit hard in the countries IGC works in. Reliable data on the economic and health impacts of COVID-19 are and will be paramount to helping governments make effective policy decisions to recover from the pandemic.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.