Does service-sector employment lead to growth? Evidence from Africa

Expansion in service-sector employment is greatly increasing across many low-income countries, but the relationship between services and potential for economic growth is less understood. In a recent study, we use micro-level data from 13 African countries to examine changes in employment over time. We look at the characteristics of those employed in services, differences across high-skill and low-skill occupations, and how these contribute to local economic development outcomes.

A central feature of successful structural transformation of most economies in the 20th century involved a shift of workers from agriculture to manufacturing. However, this pattern of economic growth and development may be less applicable to lower-income countries today than it was in the past. An important stylised fact in this regard is that low-income developing countries are moving into services earlier and at a faster rate than was observed for East Asian economies in the 1970s and 1980s. The associated ‘premature deindustrialisation’ is a potential source of concern insofar as it implies that low-income countries today cannot rely on an expanding manufacturing sector to create employment opportunities for relatively unskilled workers, drive economic growth, and increase per capita incomes. Yet others argue that services-led sectoral transformation can drive sustainable development prospects.

In a recent IGC study, we contribute to the emerging literature that analyses structural transformation in low-income economies using micro data as opposed to a focus on trade, global value chains, and broad sectoral shifts, and then aggregate indicators of output and employment at the country level. A companion project webpage provides country specific graphs and maps plotting changes in sectoral employment and occupational dynamics over time.

Structural transformation towards services: what the data says

We use the IPUMS International Database published by the Minnesota Population Center, extracting data for all African countries for which at least two censuses are available and that include information on the industry employing an individual. The resulting dataset spans 56 million individuals covering 1,546 administrative units in 13 African countries for either two or three census waves during the period of 1982-2013. The sample is representative of the Africa region, covering low- and middle-income countries, resource-dependent, and more diversified economies, and a mix of landlocked nations and countries with sea borders.

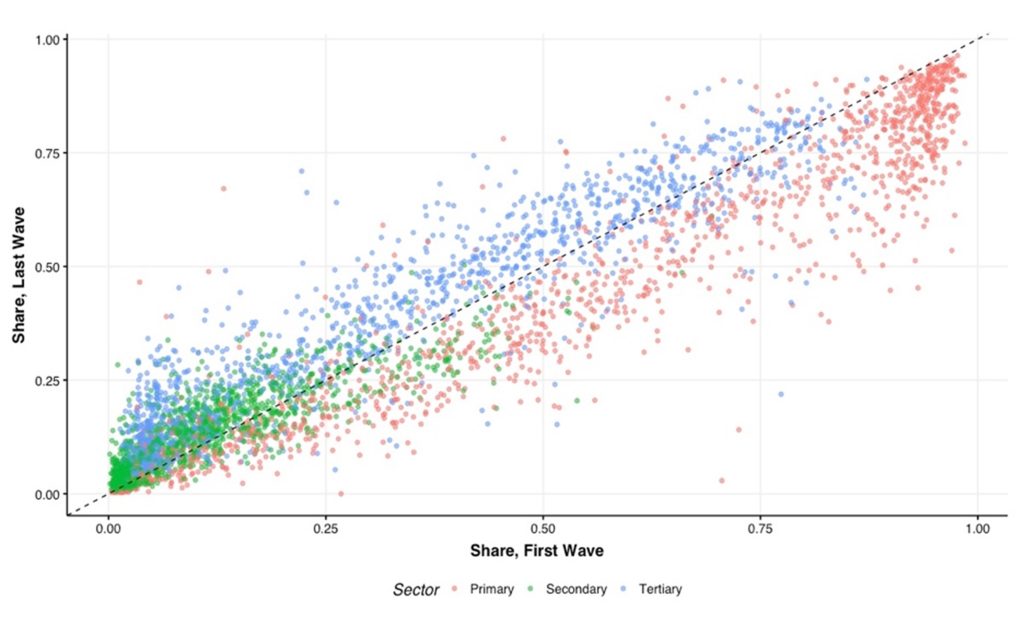

The shift towards services that is generally found at the country level is evident in our sample of sub-national units in Africa. Figure 1 plots decadal changes in employment shares across the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors. Independent of per capita income level and endowments, across all sub-national units the share of agriculture in total employment declines, while that of services increases. The share of the secondary sector generally increases as well, mostly in geographic units with a low initial base. This is offset by administrative units with initially high shares of secondary sector employment, which often register a reduction in employment share over time.

Figure 1. Change in sectoral employment shares at the sub-national level

Note: Each dot represents an administrative unit that is observed over two successive waves of the census.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on IPUMS.

Who works in services?

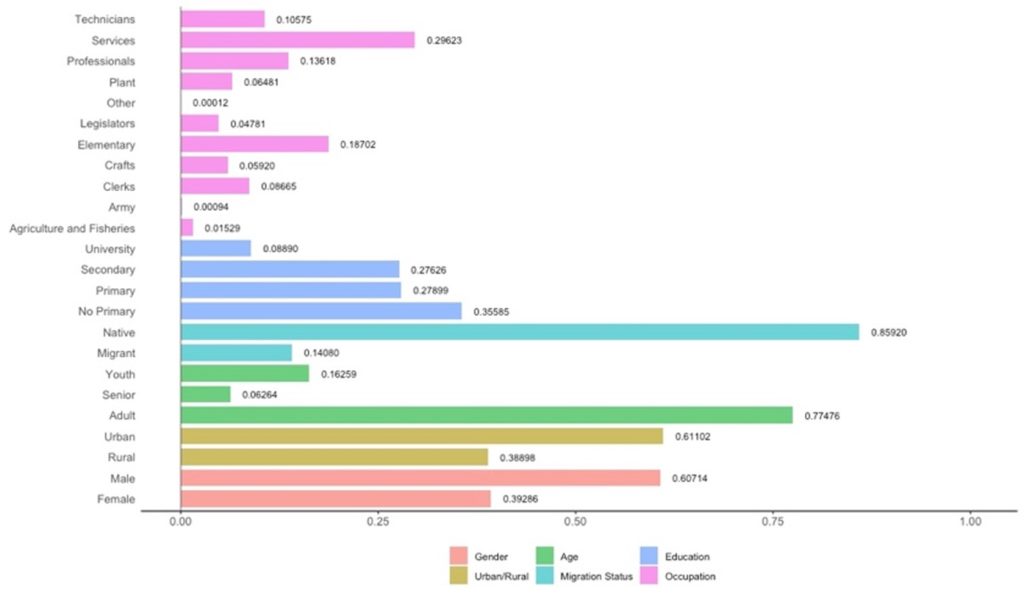

While services are a major source of employment in Africa, surprisingly little is known about their characteristics and their composition. In our paper we decompose the characteristics of workers according to the following dimensions: gender, urban/rural residence, age cohorts, migration status, education, and occupation. Figure 2 summarises the average characteristics of workers in services across all the countries included in our sample. Compared to manufacturing, services workers are on average more educated, engage in higher skilled occupations, and are more likely to be women – 40% of employees are women, twice as large as in manufacturing. Some of the more skilled occupations are concentrated in services, including education. Overall, 8.9% of those employed in services hold a university degree (compared to 2.8% in manufacturing) and 27.6% have a secondary school level education (compared to 15.1% in manufacturing).

Figure 2. Characteristics of workers in the services

Source: Authors’ elaboration on IPUMS.

Services and economic development

Exploratory analysis of the relationship between services and economic development using per capita nightlight luminosity as a proxy reveals substantial heterogeneity. We distinguish between high- and low-skill service sectors by sorting service industries by intensity of use of workers with a university degree and engagement in occupations that are more complex. Sectors that use these categories of workers more intensively than the average observed in manufacturing are classified as high skill. Disaggregating the tertiary sector by skill intensity reveals that only higher skilled services are strongly associated with development. We also show that the strong positive association between high-skill service sectors and development is mediated by geography, institutions, and technology. Greater incidence of malaria, the presence of a mining facility, and below average mobile phone coverage in an administrative unit reduces or undoes the significance of the positive association.

Sustaining development over the long term

An important open question suggested by our findings concerns a potential trade-off in the capacity of different types of services to increase productivity and employment. While lower skill service activities may have less potential to support growth, they do generate jobs and thus income. While recent research shows that firms in certain services can scale up while improving productivity performance by using new technologies and that “industries without smokestacks” often have above average productivity performance, more evidence is needed from African firms to understand the longer-term opportunities and implications of structural transformation towards services.