Environmental relocation and firm outcomes

Industrial relocation policies have become increasingly popular as a policy tool to combat pollution in the developing world. Using Economic Census data from 2005 and 2013, this article examines the impact of an industrial relocation policy in Delhi, and shows that relocation caused a long-term change in the location and concentration of firms. The data also indicate distributional consequences – with firms that were relocated across larger distances being less likely to remain open in the long run.

Location restrictions that seek to limit pollution exposure have a long history, starting with the first zoning laws introduced in the early 20th century in New York in part to improve environmental quality (Wilson et al. 2008). More recently, industrial relocation policies to combat pollution have become an increasingly popular policy tool across the developing world (Bai 2002). In India, a primary means of reducing pollution in Supreme Court-ordered Action Plans for 17 cities was relocation of polluting industries to certain designated areas, with 14 of the Action Plans in major cities mentioning industrial relocation (Harrison et al. 2015). Similar to zoning laws, the objective is to improve environmental quality by relocating polluting firms from within cities to less populated areas.

However, there is limited evidence on how effective environmental relocation policies are – for instance, do polluting firms simply move back once scrutiny is relaxed, or does it cause a persistent shift in the pattern of industrial activity? Furthermore, to what extent do such policies have distributional consequences, by gender or other characteristics?

In a new IGC study (Gechter and Kala 2021), we examine a policy in Delhi, which relocated about 20,000 firms operating in Delhi to industrial areas outside the city lines. In 1999, the Supreme Court mandated the closure and relocation of Delhi firms that were either considered polluting firms, or were operating in residential areas. It also mandated that new polluting firms anywhere in the city or new firms in industrial areas, were not to be licensed (there were some exemptions for certain types of household industries). Currently-operating and all new manufacturing firms in designated sectors were to be relocated by the Delhi government into one of several industrial areas that had been redeveloped for the purpose, and which were outside city limits. The policy also mandated that firms from polluting industries, which are ineligible for the industrial areas, leave the district entirely (the polluting status of industries was designated by the government).

Relocated firms were largely small manufacturing units, producing goods like machinery, rubber products, and automobile parts. The policy covered most districts in Delhi, though there is regional variation in the extent, with South Delhi being the least affected, due to a lower baseline number of firms that were relocated. The scale of the policy provide a unique opportunity to study the efficacy and consequences of relocation policies.

Studying industrial relocation policies in Delhi

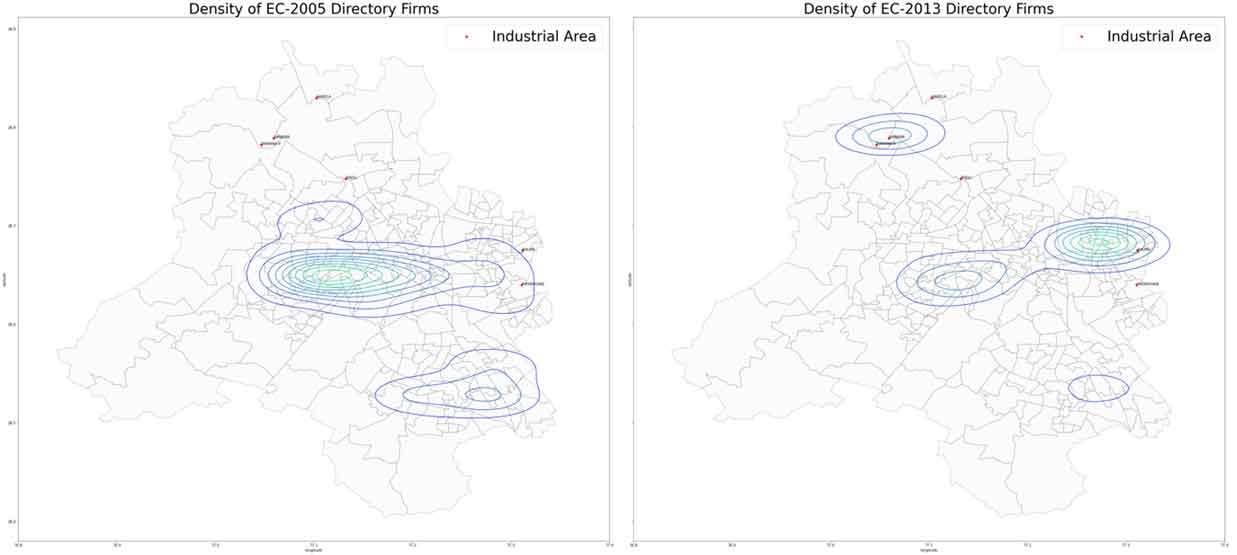

Figure 1 shows the density of firms in one of the relocated industries – furniture manufacturing – using data on firm addresses collected by India’s Economic Census1 in 2005 and 2013.2 We see a clear relocation of firm activity from the central and southern parts of the city to the eastern and northern region of Delhi, where the industrial areas are located. These – and similar case studies – show that for at least some sectors, relocation caused a persistent change in the location and concentration of firms in the longer term. For instance, 13.19% of furniture manufacturing firms were in Central Delhi in 2005, and this dropped to about 5% in 2013.

Figure 1. Density of firms in the furniture manufacturing sector, 2005 and 2013

We use data collected by the Delhi State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd (DSIIDC) in 2018, over 15 years after the policy was instituted, to test how firms fare in this regard, and how baseline characteristics predict firm survival in the industrial area.

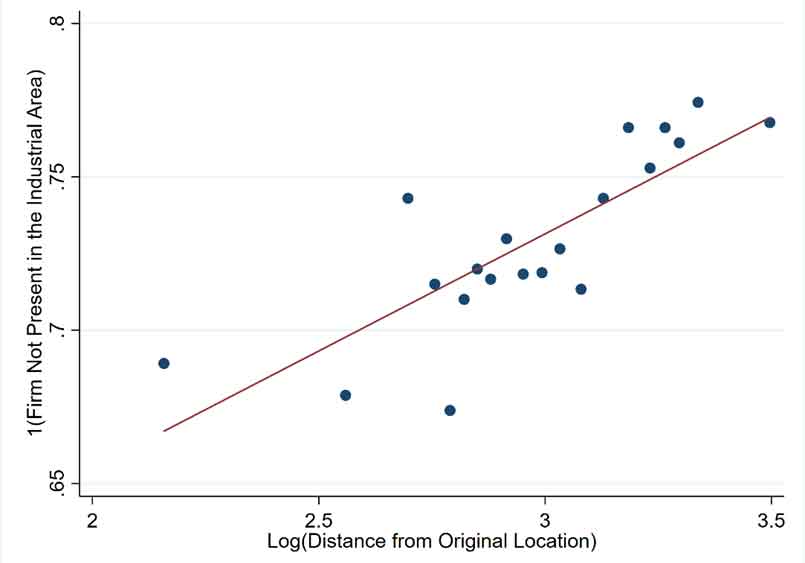

Firms relocated across large distances may be further from their suppliers or customers after relocation. This may translate into greater probability of exit from the industrial area. On average, firms were relocated about 20 km from their original location, which can be a significant transport cost if undertaken regularly and in congested parts of the city. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the distance where a firm was originally located, and its new location in the industrial area. Indeed, there is a positive, and statistically significant relationship – firms that were relocated from further away are less likely to continue operating in the industrial area.

Figure 2. Distance from the original location vs. firm exit

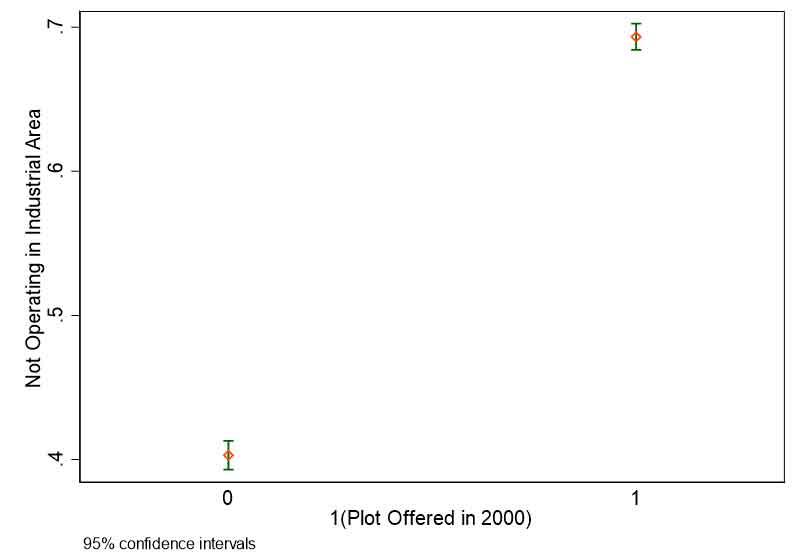

Furthermore, we test whether firms that received plots early in the policy process (in 2000) are less likely to be using the industrial areas in 2018. Figure 3 shows this is indeed the case – firms that were alloted a plot in 2000 are 30 percentage points less likely to be present in the industrial area, a large effect.

Figure 3. Impact of earlier relocation on firm presence in industrial areas

Note: A 95% confidence interval is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects. Specifically, it means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Concluding remarks

The trade-offs between promoting economic growth while minimising externalities such as pollution, are among the key dilemmas facing policymakers. Understanding the economic and distributional consequences of policies that seek to reduce air pollution by impacting firms, is important to inform policies that balance this trade-off. Furthermore, since many of these policies impact firm decisions, they also provide a lens to test theories of firm interactions that contribute to our understanding of firm behaviour.

Editor’s note: This blog was first published in Ideas for India and is based on this IGC project.

Notes:

- The Economic Census is conducted by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

- The 2005 Economic Census collected address information for all firms employing 10 or more workers, and the and 2013 Economic Census for firms employing eight or more workers,

Further Reading

- Bai, Xuemei, "Industrial relocation in Asia a sound environmental management strategy?", Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 44(5): 8-21.

- Harrison, A, B Hyman, L Martina and S Nataraj (2019), ‘When do Firms Go Green? Comparing Command and Control Regulations with Price Incentives in India’, NBER Working Paper No. 21763.

- Wilson, Sacoby, Malo Hutson and Mahasin Mujahid (2008), “How Planning and Zoning Contribute to Inequitable Development, Neighborhood Health, and Environmental Injustice”, Environmental Justice, 1(4): 211–216. Available here.