The framing of violence against women as a public health issue allows for more robust multi-disciplinary interventions through the healthcare sector and necessitates analysis of the sector’s capacity to recognise, intervene, and prevent GBV.

Gender-based violence (GBV) is recognised as a complex health problem rooted in patriarchal social norms and the economic deprivation of women. It is a severe human rights violation. The public health approach to GBV marks a paradigm shift away from social-legal approaches or private inter-personal matters to a health issue underpinned by structural inequalities between women and men (Burman and Öhman, 2014). GBV increases the burden on women's health, and evidence shows it has high economic costs and implications for national growth and development (Duvvury et al., 2013). Increased economic costs are due to the higher likelihood that women victims of violence would need to seek health services and incur out-of-pocket expenses in the absence of health insurance or public health systems. Women's empowerment is a means of mitigating GBV at intra and inter-household levels. LSE Professor Naila Kabeer defines empowerment as "the expansion in people's ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them”. This ability needs to improve on three inter-related dimensions: resources (access to and claims over material, human, and social resources), agency (processes of decision-making), and achievements (well-being outcomes) (Kabeer, 1999).

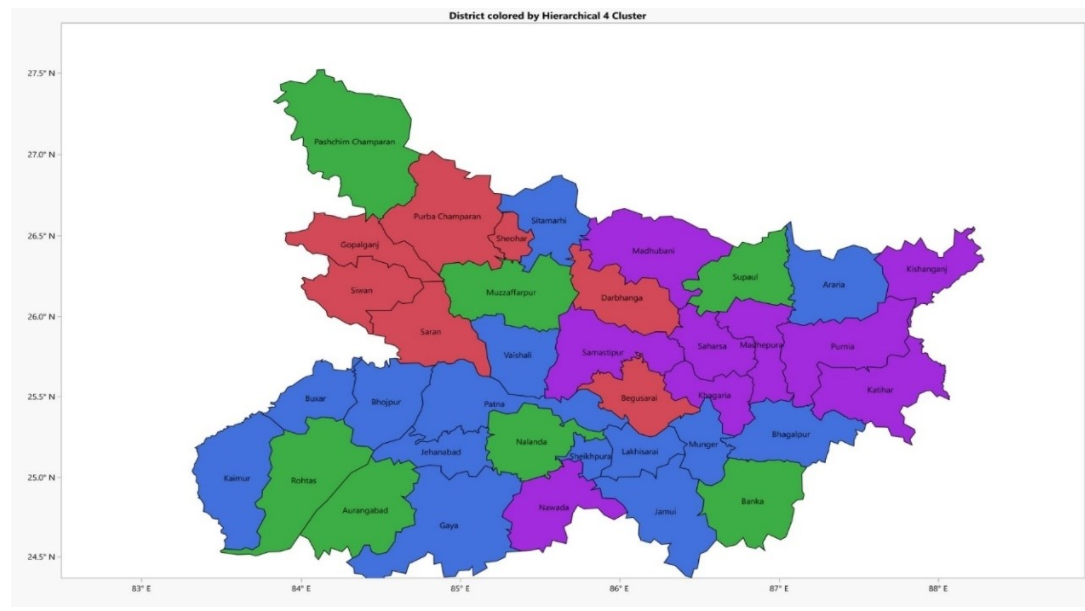

My study fleshes out empowerment indicators based on the existing prevalence and incidence of GBV in Bihar, India by examining the social-cultural, economic, and legal-political determinants of GBV and its relationship with women’s empowerment. I theoretically draw on social-ecological models, norms and philosophies to illustrate the complex interlinkages between intra-household intimate partner violence and the continued prevalence of physical, social, economic, and cultural violence against women in public spheres. The prevalence and incidence of adverse health outcomes of GBV across Bihar sub-units districts was measured alongside geospatial heat maps developed to facilitate in identifying hot spots of GBV. Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to develop indices that encapsulate the multi-dimensionality of empowerment (Vyas and Kumaranayake, 2006) as well as composite indicators to understand the prevalence and incidence of GBV in Bihar (Saisana, 2014), I perform a district-wide analysis of the prevalence of various types of GBV and its consequences on women's health. The study also initiated a formative pilot of Identification and Referral to Improve Safety, UK (IRIS)/ Healthcare Responding to Violence and Abuse (HERA) (IRIS/HERA Model) of Complex Interventions of GBV in tertiary health care settings (Feder, et al., 2011).

Understanding GBV in Bihar districts

The overall empowerment of women in Bihar is of grave concern. In the National Family Health Survey (IV), 90% of women in Bihar did not have any health insurance plan, 83% were currently not in the workforce, and 72% did not have any bank account (International Institute for Population Sciences, 2015-16). In terms of prevalence, it includes indicators for various forms of violence such as: never been kicked or dragged, never been humiliated, never been threatened with harm, never been physically forced into sex, and never had severe burns. Figures 1 shows Gaya, Kaimur, Jehanabad, Patna, and Vaishali (highlighted in blue) are better-performing districts in terms of both prevalence and incidence of violence. On the other hand, districts with high prevalence and incidence of GBV include Saran, Siwan, Gopalganj, Purba Champaran, Darbhanga, and Begusurai (in red).

Figure 1: Prevalence and incidence of violence by the district.

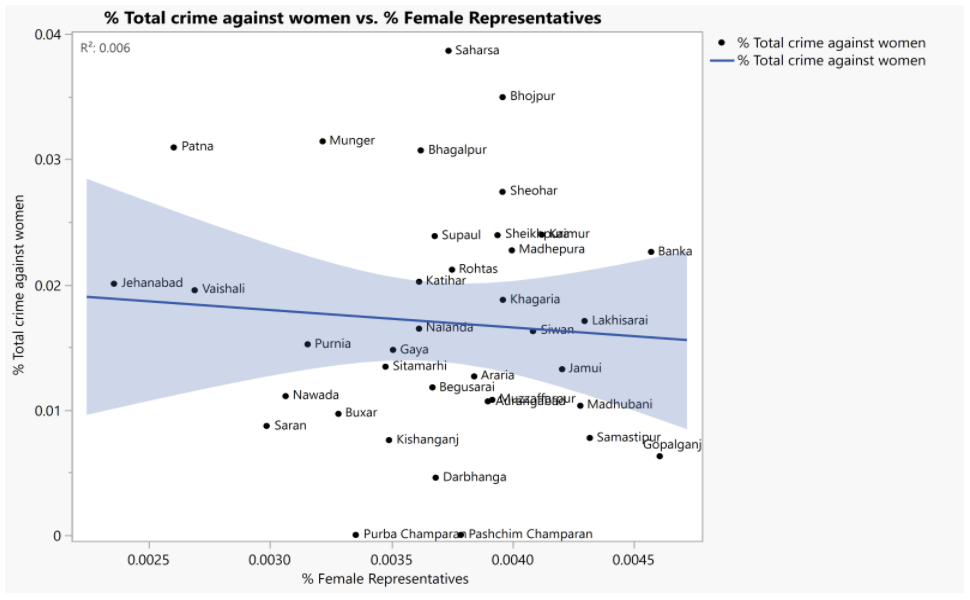

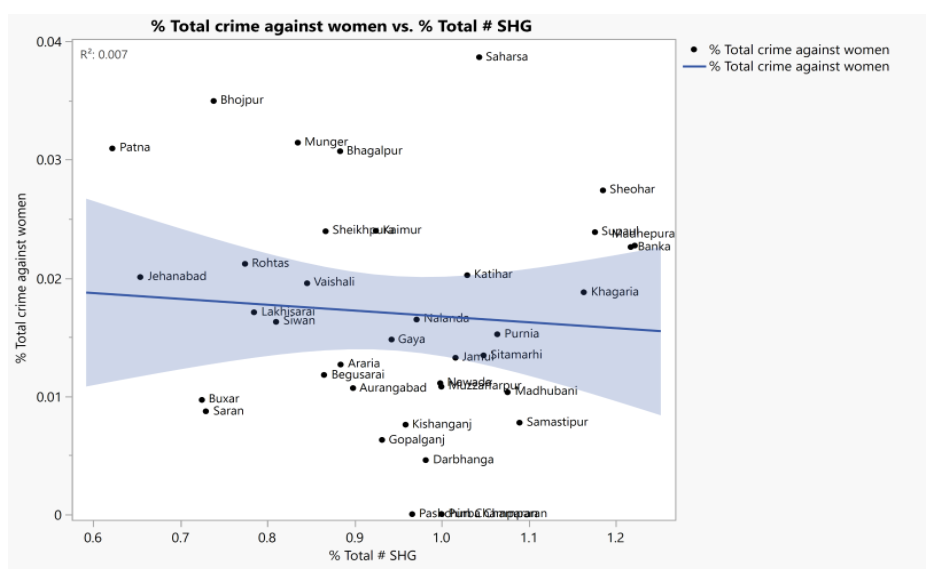

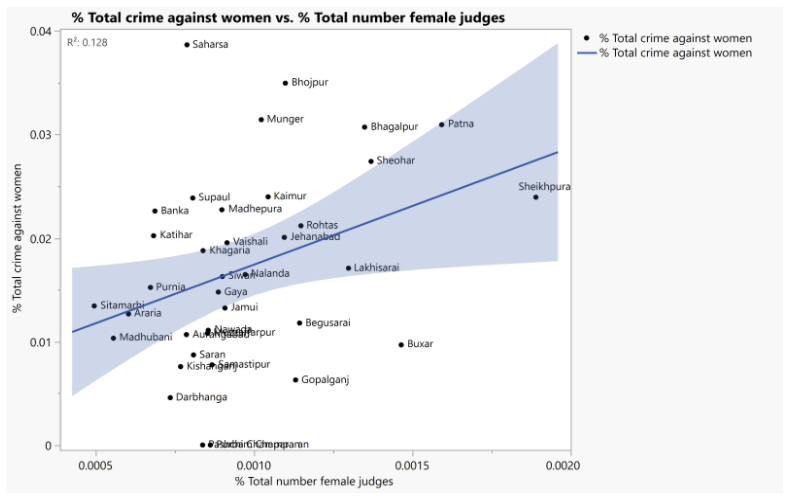

Figure 2 shows a positive correlation between mild to severe violence and improvements in women's representation in districts based on National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. Figure 3 shows no significant relationship between total crimes against women and financial self-help groups (SHGs), potentially due to randomness of the data. As NCRB data indicate the reported and registered cases of crimes against women, the data may also signal that woman in SHGs report more cases. Existing evidence does show that women's economic empowerment leads to more significant male backlash (Abramsky et al., 2019; Bhalotra et.al,. 2019). For example, Madhepura and Nawada districts have a high number of SHGs yet also report higher instances of humiliation by husbands. Women in Buxar report severe threats with knives or guns, despite having SHGs.

Figure 2: Female representation and crime against women.

Figure 3: District-level analysis of relationship between SHGs and NCRB

Figure 4: Correlation between crimes against women and female judges.

Healthcare responses to violence and abuse in Bihar

Few public health interventions for domestic violence within developing countries have undergone rigorous evaluation (Bacchus et al., 2021). In the second part of the study, interventions based on the WHO guidelines on domestic violence (World Health Organization, 2013) and HERA)/IRIS (Feder et al., 2011) were carried out in two Bihar hospitals. IRIS is a general practice-based domestic violence training, support, and referral programme for primary care staff. The HERA Model is based on the Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS), a part of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). Unlike IRIS, the HERA Model includes community-based organisations as developing countries might not have universalised health systems like the UK.

For this study, the IRIS/HERA intervention training for early identification and referrals to support services for victims of domestic violence and abuse (DVA) was conducted in gynaecology, surgery, orthopaedics, and burns and plastic surgery in two Bihar-based tertiary hospitals. A considerable number of healthcare providers were in the 30-34 years age group. Amongst the providers, 63.9% and 35.5% were females and males, respectively. Of these, general MDs (8.3%), specialist MDs (57.4%), staff nurses (27%), mid-wives (1.8%), and clinical/unit heads (1.2%) undertook the training. Most Health Care Providers (HCPs) had no systematic training in the early identification of DVA or making referrals to the support services.

- The initial baseline study shows that HCPs recognise the signs and symptoms of DVA. Such as physical injuries, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, irritable bowel syndrome, headaches, depression and anxiety, hypertension, eating disorders, sleep disruptions, general stress, STIs, frequent vague complaints, unkempt appearances, and disability.

- From the HCPs, 58% did not have any information on DV care pathways and referrals support and 52.1% had no awareness of DV support for women. Only 10.1% of HCPs were aware of the one-stop centres (OSCs), and 24.9% knew of the women's police station (Mahila Thana). Only 10.1% knew of women's hostels, and 5.9% knew of shelters.

- Our intervention training with HCPs in Patna showed improved knowledge of domestic violence and child protection. Despite the limited availability of information on OSCs, HCPs raised concerns about the quality of care provided to victims and the lack of follow-up reports for cases referred by them, casting doubt on patient safety and HCP reputation and credibility.

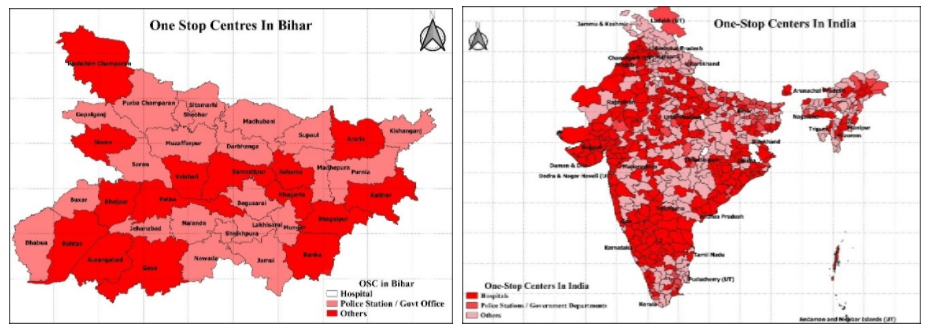

Figure 4 (a & b): OSCs in health care settings in Bihar and India

Source: Compiled from the Ministry of Women and Child Development (23) (Department of Women and Child Development, GOI, 2020)

Source: Compiled from the Ministry of Women and Child Development (23) (Department of Women and Child Development, GOI, 2020)

Policy implications

- Bihar remains a high-prevalence state for GBV and adverse health consequences for women, and this is reflected in poor empowerment indicators. Aurangabad, Pashchim Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Patna, and Sitamarhi are relatively better-performing districts. Saran, Siwan, Gopalganj, Purba Champaran, Darbhanga, and Begusurai are the worst-performing districts in terms of prevalence and incidence of mild to severe forms of domestic violence. Also, improved women's representation worsens GBV, confirming the mixed global evidence on women's empowerment and male backlash. Gender-based interventions focusing on prevention are therefore critical to improving women's outcomes.

- In the last decade, setting up the OSCs in Indian healthcare settings has been a significant policy response to mitigating GBV. Although the OSC model is gaining momentum across India, few of these are rigorously tested and we do not have robust evidence to show their efficacy in reducing GBV and achieving better social and economic outcomes (Olson, et.al. 2020; Verma, 2020; Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2021). Bihar currently has no OSC in health settings. Figures 4 (a and b) show that in comparison with India, the existing facilities in OSCs are minimal and inter-sectoral collaborations are non-existent. Healthcare-based OSCs in Bihar would be an essential stepping-stone for multi-sectoral, complex intervention models. However, OSCs are also under scrutiny for the inadequate quality of care and support provided to women victims of violence and are primarily based in urban areas. Therefore, JEEVIKA's1 SHGs are an essential link to expanding GBV interventions into the rural areas of Bihar. Leveraging the women's self-help groups movement in Bihar and health response could also potentially mitigate the adverse social and economic consequences for women in Bihar.

- IRIS/HERA Interventions indicate that Bihar's health systems do have the capacity to respond to GBV. Emerging evidence from other IRIS/HERA models, such as Palestine, show that these public health intervention models should be aligned to local statutory and community-based services. This study shows an improved willingness of the healthcare providers to refer GBV cases to OSC after completing the IRIS/HERA training. Bihar's HCPs express reluctance due to the absence of OCS within healthcare settings, poor quality of care provided to victims, ethical concerns of privacy and confidentiality, and lack of follow-ups.

Some policy suggestions to remedy some of these issues include:

- Setting-up one-stop centres within hospitals with the active involvement of department heads and appointment of lead HCPs as DV advocates could provide a stepping-stone for the multi-sectoral health response in Bihar.

- Establishing OSCs within healthcare settings can set the foundation for incremental improvements in care pathways for women in the future.

- Improving publicity of women's helpline 181 and OSCs across the healthcare settings, with incremental improvements in quality of care for women victims and protocols for follow-ups and rehabilitation.

- Adopting the IRIS/HERA Model as the existing OSCs are neither evidence-based nor have rigorous monitoring and evaluation. A rigorously tested IRIS/HERA model can be a cost-effective approach to women’s empowerment.

This article is part of our gender equality series.