The field of economics is one of the most gender imbalanced fields in academia, skewing heavily towards men. In this blog, we focus on three inhibiting mechanisms driving these gender imbalances in the discipline, namely lack of recognition, poor work environments, and self-selection.

With only two Nobel economic prizes awarded to women (out of 89 awards) and considerable underrepresentation in senior academic positions, economics leads academic fields when it comes to gender imbalances. Indeed, globally the share of women in economics cohorts graduating at the PhD level plateaued from the 1970s to the 1990s at less than 10%, reaching just 26% in 2021. Additionally, there are far fewer women than men in tenure positions, with women representing less than a third of assistant professors and even fewer full professors in the US (see Figure 1 below).

Notably, women are less likely to receive tenure or to publish in top-ranked journals. On average, only 8% of authors per paper published in top economics journals since 1950 are women, with one in particular, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, not publishing a single exclusively female-authored paper between 2015-2017 (Hengel, 2022). Additionally, certain economic fields have higher barriers than others. The least gender-balanced fields, with less than 20% female share, are microeconomics, econometrics, and economic growth – three fields that the International Growth Centre actively commissions research for. Common gender imbalances in the workforce seemingly combine with specificities of the discipline to hinder women's access to top academic positions.

On top of equity concerns, gender imbalances challenge economics as a discipline and could be detrimental in the long-run. The disappearance of women over the course of their studies, or the ‘leaky pipeline’ (see Figure 2 below), is likely to cause a loss of talents. With women specialising in different fields than men, gender imbalances influence the content of research produced. Overall, it is puzzling that a science studying human activity remains so unrepresentative of society.

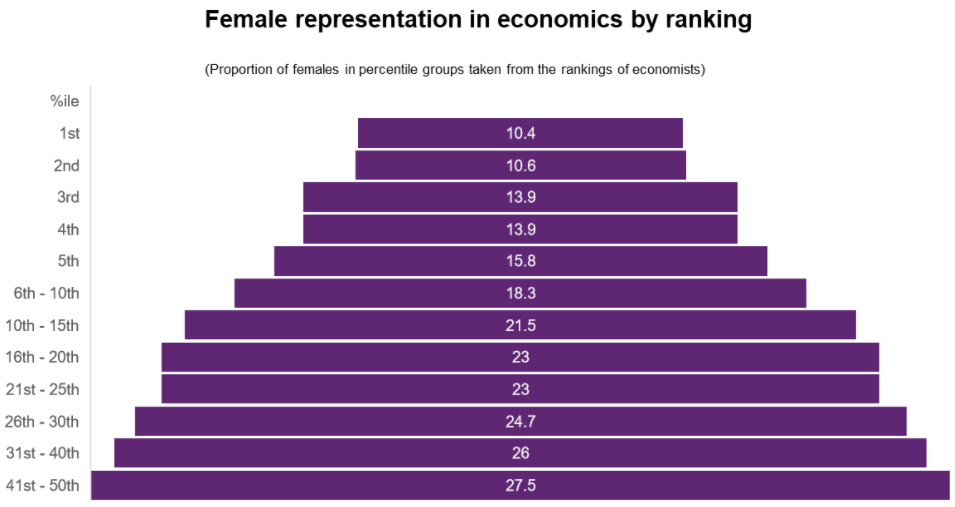

Source: Berland, O., Harman, O., Moreau-Kastler, N. (2022). Data: https://ideas.repec.org/top/female.html#cohort. Note: ‘Rankings’ are a combination of depth of research and breadth of research. Depth is measured by citations with analysis performed by the CitEc project. Breadth is measure by abstract views and paper downloads which are counted by the LogEc project. Various rankings are then established.

Source: Berland, O., Harman, O., Moreau-Kastler, N. (2022). Data: https://ideas.repec.org/top/female.html#cohort. Note: ‘Rankings’ are a combination of depth of research and breadth of research. Depth is measured by citations with analysis performed by the CitEc project. Breadth is measure by abstract views and paper downloads which are counted by the LogEc project. Various rankings are then established.

In this blog, we focus on three inhibiting mechanisms driving gender imbalances in the discipline and discuss recent academic work highlighting these mechanisms.

Recognition

Recent papers have evidenced the lack of recognition for women in economics from peers, publications, and institutions. From peers, there are important differences in how women in economics are being perceived by their community compared to men. Wu (2019) uses text mining and machine learning to analyse differences of treatment across genders on a well-known economics forum. She finds that discourse becomes significantly less academic or professional when women are mentioned in threads. The shift in language becomes more often about personal information and physical appearance. Women also receive different recognition from publications. Card et al. (2020) and Hengel (2022) look at papers submitted or published in top-four economic journals (AER, ECA, JPE, QJE) from 2003-2013 and 1950-2015, respectively. They find that papers written by women must meet higher quality standards to get published, measured in citation number and writing quality. These papers also spend a longer time under peer review. A consequence of this unfortunate higher barrier to entry is that papers submitted by female authors received 25% more citations than those authored by men once published.

There is also evidence of recognition from institutions being gender-biased. Sarsons et al. (2021) collect positions and publications for 613 academic economists at the top 35 US schools and find that while solo-authorship or co-authorship does not matter for men’s tenure prospects, tenure is less likely for women the more they co-author—exhibiting biases in credit attribution for the work. Further, invitations to women to share their research are not forthcoming. Doleac et al. (2021) found that in economics seminars across 66 US and non-US departments only 23% of speakers were non-under-represented-minority (URM) women—2% lower than the proportion of women in senior positions in the top 250 research institutions (Auriol et al., 2022). Perhaps even worse is that less than 1% of speakers represented URMs, men or women.

Work environment

Various factors in the economics discipline can also hinder female economists’ well-being and success. Among these are differences in how they are treated at work. This is the case for online forums as suggested above by Wu (2019), but also during research presentations. When women are invited, they experience a different seminar environment. Dupas et al. (2021) collect data on every interaction between presenters and their audience for several hundreds of seminars and conferences. They find that women get more questions than men on average, and that question types differ across genders, with questions for women more likely to be patronising or hostile. New practices have emerged as a response to these differences in treatment. Some institutions have ground rules for their seminars—for example, forbidding interruption during the introductions.1 Others are using non-gender-mixed PhD seminars to ensure a constructive research setting. Overall, more could be done to ensure these negative interactions and prejudices are mitigated in work environments.

Perhaps as a consequence of the above hostility, women also tend to have smaller networks and fewer co-authors. Ductor et al. (2021) find that these differences explain a significant part of the gender output gap, about 18%. The emergence of female networks and research events might help in reducing this gap. One such example is the new initiative Women in Economics Paris-Saclay, started at the end of 2021 by two of the authors of this column. It aims at strengthening female networks and targeting gender imbalances in the discipline by promoting research on the topic.

Self-selection and career choices

The final barrier of self-selection is far more prominent as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions — particularly the self-selection into gendered roles. Early evidence from Alon et al. (2020) show lockdowns’ effects on many professions, with increased childcare needs from school closures falling more heavily on working mothers. Surveys from Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) show mothers working from home spend between 1-2 more hours per week home schooling and caring for their children than fathers working from home. Similarly, Andrew et al. (2020) highlight that mothers spend a higher proportion of paid work hours juggling work and childcare, and mothers who do stop working for pay contribute to more domestic work than fathers in the same position.

Gabster et al. (2020) document initial consequences of pandemic-related barriers to academic publishing with only 30% of overall authorship of The Lancet’s COVID-19 publications coming from female academics. Within this, there was inequality depending on authors’ country of residence. More than 60% of authors are affiliated with high-income countries, particularly in Europe and Central Asia. Economists in low- and middle-income countries may have felt the strains differently. In Uganda, for example, schools were closed for 22 months, and the effects of the closures on the country’s female scholars remain to be seen.

Changes in the culture of economics

Over the last two decades, we observe rising interest in addressing gender imbalances in the economics discipline. This is illustrated both by the growing body of research on this topic, and by recent academic initiatives dedicated to women’s representation. We can cite over ten formal women in economics support networks and many local clubs and associations. Among the most well-known institutions driving this are the American Economics Association (CSWEP) and the European Economics Association (WinE). Additionally, events such as conferences and retreats are also being organised to foster networking and research diffusion. Groups like WEPS that are sharing research and learning about gender imbalances can further aid in removing barriers for women in economics.

However, more research on gender inequity in economics is needed, particularly examining how there are relatively more women in top economic policy positions, yet this does not filter through to academia. Additionally, we need more knowledge on how to make women's ability to be mobile and flexible, do fieldwork, and attend conferences compatible with family duties and caring responsibilities in various socio-cultural contexts. While there is still a way to go in bridging the gender gap, understanding the mechanisms behind female participation in the economics field and removing these barriers can help us do better as a community.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our gender equality series.

Authors’ note: WEPS is a new initiative at University Paris-Saclay started by two PhD students aiming to strengthen female networks and target gender imbalances in the discipline by promoting research on the topic. Please reach out to the authors to get involved. To learn more read Pipelines or pyramids: A review of barriers for women in economics.