The pandemic’s gendered impact on livelihoods and wellbeing: Evidence from India

A survey of over 700 households from India’s National Capital Region finds that women report bearing a greater burden of pandemic-induced mental stress relative to men, with potentially lasting effects on their well-being and productivity.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our International Women’s Day campaign and is based on this IGC project.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent nationwide lockdown, India faces significant policy challenges, both humanitarian as well as economic. Vast numbers of its population of 1.3 billion people are self-employed informal sector workers and daily wage earners who lack access to social security. Many of these workers are facing job and income losses, and food shortages, and require direct support in terms of cash and food. It is also becoming increasingly apparent that significant mental health concerns have arisen in the face of the pandemic and the lockdown, both due to the economic uncertainty as well as the social distancing measures, which have impacted community connectedness.

In this article, we report the short-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment and mental health outcomes among a subset of India’s economically vulnerable population in crowded urban settings. The data comes from over 1,000 households with couples aged 18-45 residing across five industrial districts of Delhi and the surrounding National Capital Region (NCR). It covers two periods through in-person surveys conducted pre-pandemic in May 2019 and a follow-up “post-pandemic” phone survey conducted in April-May 2020.

The post-pandemic survey was conducted over two phases: Phase 1 (3-19 April 2020) coincided with the most stringent period of the national lockdown, and Phase 2 (20 April-9 May 2020) was at a time when some mobility restrictions were being eased. Since the survey dates for respondents were randomly selected, respondents interviewed in the two phases are mostly similar in socioeconomic characteristics. Therefore, any difference in responses of these comparable samples can be attributed to the length of their exposure to the lockdown.

How much has men’s employment been affected by COVID-19?

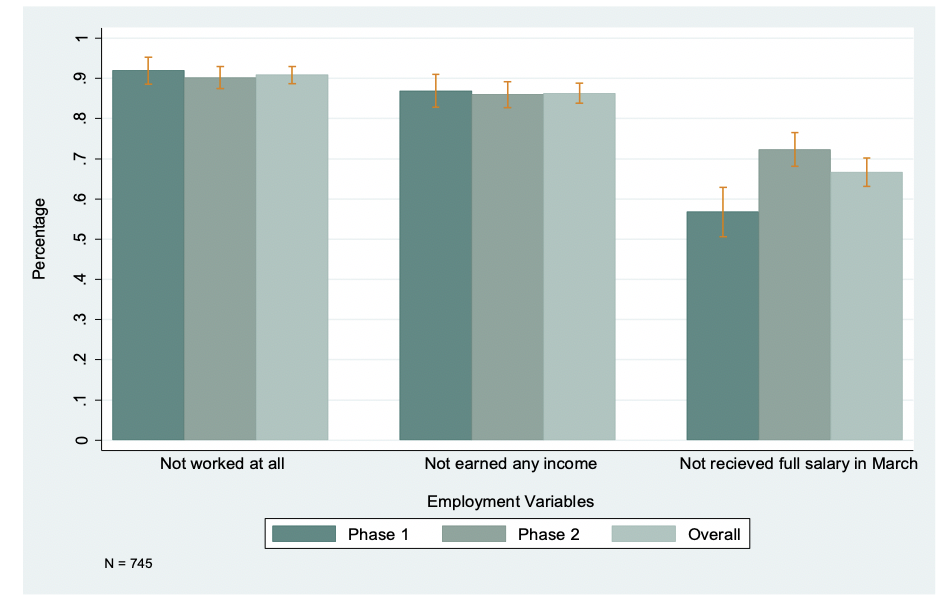

Figure 1

Figure 1

Overall, as shown in Figure 1, the pandemic and subsequent lockdown led to a massive shock to the livelihoods and wage earnings of the participants. As expected, approximately 90% of the men were completely unable to work, and this situation did not improve over time as suggested by the responses received in Phase 2. Consistently, around 85% of the respondents did not earn any income from their main occupation during this period. The proportion of respondents reporting non-receipt of full wages is 14 percentage points higher in Phase 2 than in Phase 1.

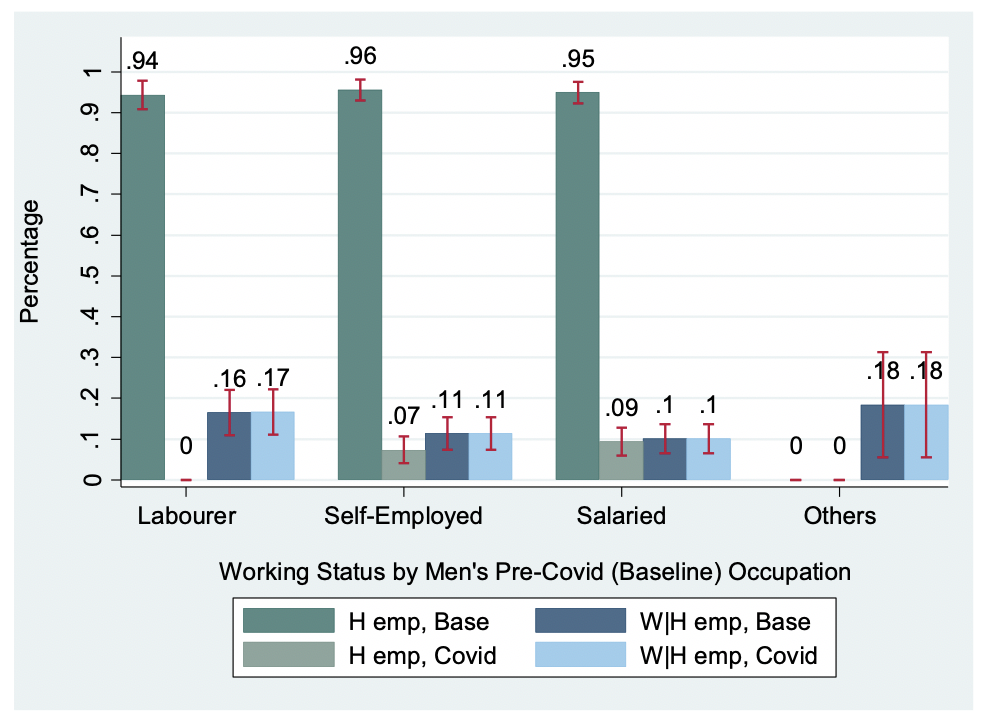

Analysing self-reported employment status of husbands and wives between 2019 and 2020 from panel data consisting of 1,034 pre-pandemic and 745 post-pandemic households, we find that men’s self-reported employment status declined by 89 percentage points post-pandemic, relative to the pre-pandemic period. This is primarily driven by wage and casual labourers who experienced nearly a 91 percentage point reduction in employment, followed by the self-employed and salaried workers.

Did COVID-19 have the same effect on women’s employment status?

Figure 2

Figure 2

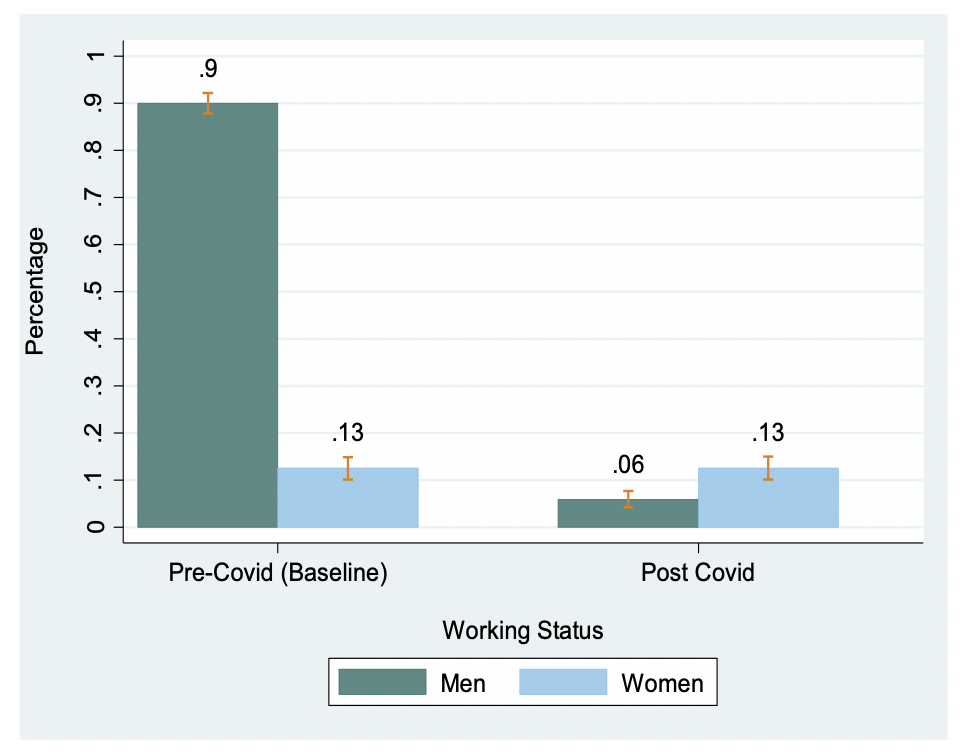

Since our data consists of male (husband)-headed households, we have considered husband-reported women’s employment status for this analysis. In contrast to the large negative impact on men’s employment, we do not find any significant change in women’s employment as reported by their husbands in the post-pandemic period (see Figure 2).

Figure 3

Figure 3

Has mental stress worsened during the pandemic?

Since most women in this sample did not own a personal phone, the post-pandemic phone survey was conducted with their husbands as the main respondent who reported their own and their wives’ employment status. However, women were interviewed separately for the mental health questions. This provides us with matched husband-wife mental health outcomes post-pandemic and gives a unique insight into the gendered experience of the crisis in 745 households.

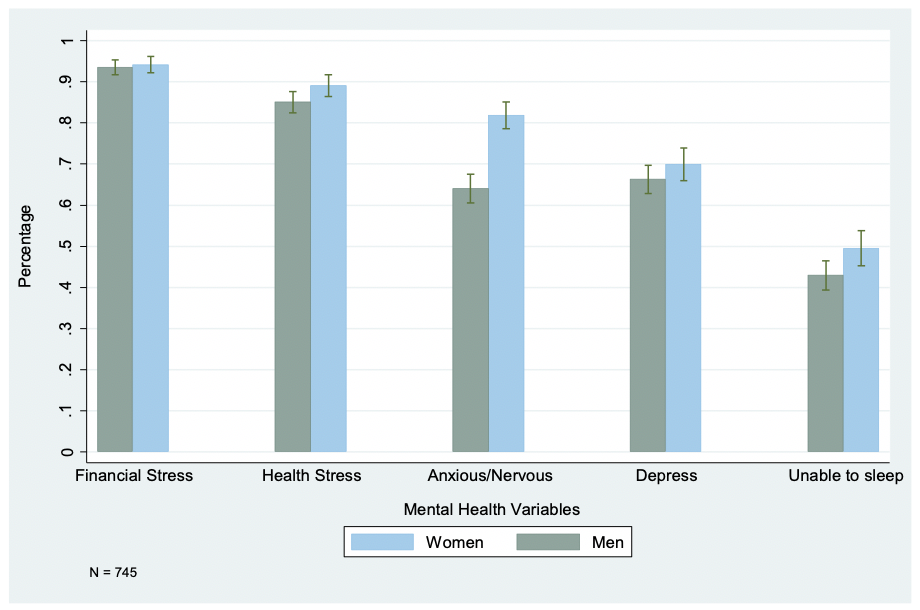

Figure 4

Figure 4

As shown in Figure 6, mental stress was reportedly remarkably high during the pandemic, driven primarily by financial (90%) and health concerns (85%). Consistent with emerging evidence, women appear to be suffering from greater mental stress than men (see Figure 4). For example, 90% of women report feeling worried about the physical health of their families, compared to 85% of men. Strikingly, both men and women worry more about their family’s financial adequacy than about their health, though the difference is not significant. Almost 82% of women felt anxious or nervous about the current situation, compared to 64% of men, and more than a third of both women and men reported having trouble in getting adequate sleep.

On further analysis, we find that women appear to be bearing a greater burden of pandemic-induced mental stress relative to men, which corroborates our descriptive evidence from Figure 4. Women report significantly greater mental stress compared to men.

Do social networks have a role to play in increased mental stress?

Pre-pandemic data on men’s and women’s social networks – including their size and nature – shows a stark difference in the impact of network size on their mental health, with larger network size reducing mental stress for men and increasing it for women. In other words, own social networks appear to have a mitigating effect on men’s mental health, but an exacerbating effect on women’s mental health, especially in times of crisis.

Further, by disaggregating social networks (as measured in pre-pandemic survey) into three categories – home (parents, cousins, siblings, in-laws, and other relatives), work (co-workers), and neighbourhood (friends from same locality, lane, or block, previous locality, and native village) –

we find that the negative marginal network effect on women’s mental well-being is driven by “home-bound” nature of women’s networks. While for men, having an additional “home friend” lowers their mental stress, for women, it almost doubles their reported mental stress. A similar pattern is observed for “neighbourhood-friends” in terms of effect size and direction, although the estimated effect for men is no longer statistically significant. In contrast, “work friends” lower mental stress for both men and women, although neither is statistically significant. These findings require a more in-depth exploration of gender differences in the structure of social networks.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the relevance of understanding the impact on mental well-being (besides livelihoods) of this unprecedented crisis on vulnerable populations – particularly on women. The pandemic’s longer-term adverse impacts may be greater on women’s wellbeing and productivity, particularly in India and other developing countries.